This post is adapted from the blog of RentHop a Priceonomics Data Studio customer. Does your company have interesting data? Become a Priceonomics customer.

***

A widely unpopular practice (and illegal in most states), price gouging is when sellers take advantage of a disaster situation to excessively raise prices on essential goods like food, fuel, and shelter. Concern across communities about this problem is especially heightened after the past several months of storms, forest fires, and other disasters.

Houston, recovering from the damage inflicted from Hurricane Harvey, is no exception. The office of Ken Paxton, Texas Attorney General, reports receiving upwards of 5,000 complaints – regarding everything from food to home repairs. In an incident that elicited enough outrage to spark a viral news story, a Best Buy was criticized for selling a case of water for $42.

But price gouging is not always as clear cut and visible as water marked up 200%. In an interview with Fox News, Paxton explained his office’s approach for monitoring the situation, “We try to be reasonable in how we’re dealing with this. The general rule is, if it goes up 10 percent or more, and it’s above like a three-month average, we’re going to look at it.” The measured approach is likely because, in many cases it’s difficult to draw a line between honest price increases and predatory practices.

Source: CNBC

One area that is especially difficult to monitor, but increasingly important to vulnerable residents is rent. The concern is that with the widespread destruction of so many homes, the housing supply will be severely limited, resulting in price increases. Displaced residents can’t hold out for fair prices and landlords who understand they are in a position of power over these desperate renters, could inflate prices unfairly. This is no small issue either. A 2015 census estimate puts the number of Harris County residents who rent at about 45%.

Price increases could also be exacerbated by the fact that Houston is already a market with high demand. Between 2010 and 2016 the the city has increased in population by about 10% (to 2.3 million) and broader Harris County by about 12% (to 4.6 million).

So, are we seeing an increase in rental prices in the Houston area since Harvey? We decided to analyze data from Priceonomics customer RentHop, a real estate marketplace covering major markets in the US, including Houston. By comparing prices in Houston before and after the disaster, we can identify price changes that seem questionable and investigate further.

According to our data, while the Houston area overall saw a decrease in median rental prices of approximately 15%, certain zip codes experienced moderate price increases. In total 19 zip codes increased by 10% or greater after the hurricane, meeting the threshold for “price gouging”. Additionally we’ve seen an uptick in the maximum daily price for listings, with one and two bedroom units seeing most of the impact over the past 50 days.

***

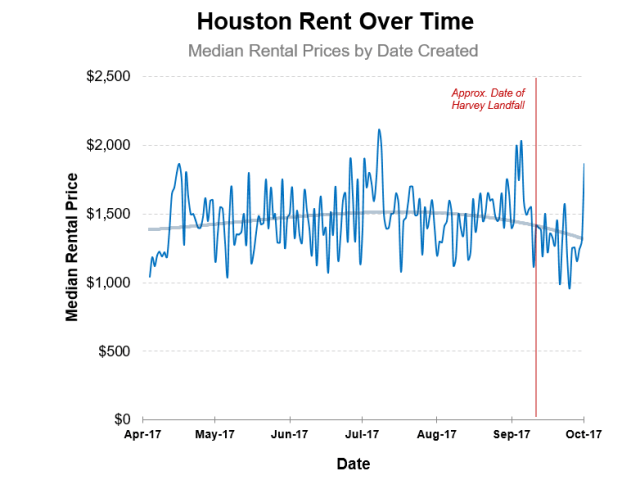

The first logical analysis is to summarize price over time. Overall did we see any kind of change in the Houston housing market? For each day within our dataset (April 18th through October 15th) we’ve calculated the median price, plotting the results to reveal a trend.

Data source: RentHop

The data it not immediately clear because of the variation between days, but using a polynomial regression line, we can see a downward trend since mid-July, continuing through the events of the hurricane around August 25th. This actually makes sense. Generally housing markets are seasonal, with the highest prices in summer and lowest in winter. Prices in autumn should continue to decrease, which is what we see.

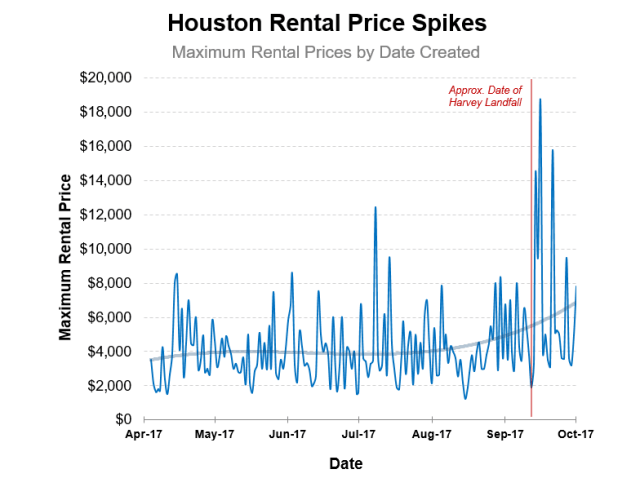

The median price may not be suited for identifying price gouging. These gouger-prices would be at the extreme high end of the spectrum, and would not be frequent enough to move the median in a meaningful way. A better statistic to track would be the daily maximum price. In the same manner we’ve calculated the maximum price for each day in our dataset and plotted them along with a trendline.

Data source: RentHop

Again we see strong fluctuations between days, but in general the trend is smooth until around early September where much sharper peaks pull the line upwards. It is important to note that there are price spikes throughout this time series. From this plot we can say, since Harvey, the highest price for each day is getting bigger. Another interesting detail is that the max price bottoms out around the last week of September (the week of the hurricane), but then quickly rebounds.

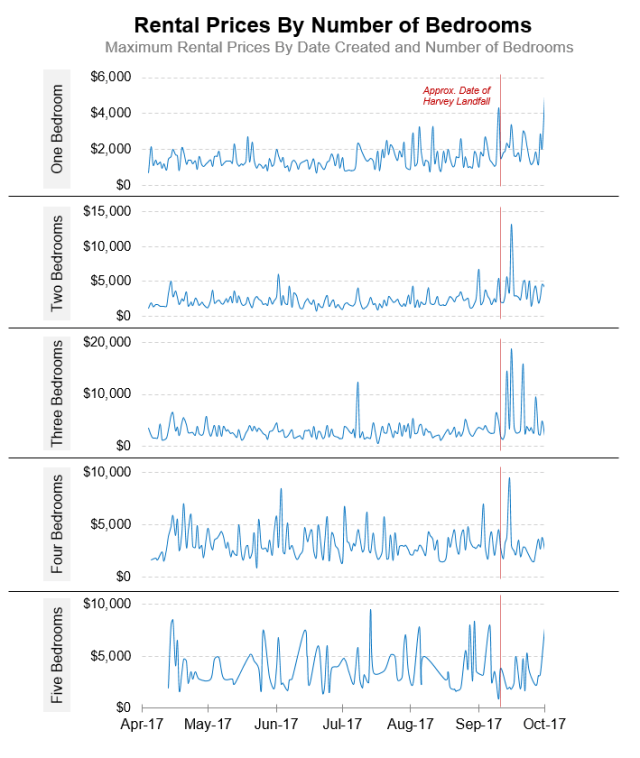

We want to get more specific though. Right now we are looking at a whole range of apartments and our data includes small studios through large single family homes. It is possible that the price spikes we see are because more valuable homes are being put up for rent. What if the month of October had an abnormally large number of mansions put up for rent? While not likely, that is an alternative explanation for this price spike that does not involve gouging. We need to compare apartments that are similar in value and see if there are differences.

The best indicator of rental value is number of bedrooms, so we’ve used it to split our data for comparison. Below we’ve plotted max rental prices for one through five bedroom listings. Any price spikes within a category could be more meaningful than just a general change.

Data source: RentHop

Looking more closely we see that one and two bedroom listings are experiencing an upward trend in maximum prices. There are more instances of high peak prices from September onwards. It’s important to note that these listings also make up the majority of the rentals in our dataset. Even when adding measures to control for rental value, we are seeing a change in prices after the hurricane.

Another big influence on price is location. In a metro area as broad as Houston, there are plenty of differences between neighborhoods that could result in a difference in price. One of the most obvious examples would be comparing the rent in the heart of downtown to rent in the outer suburbs. We would expect downtown to be more expensive. Additionally there could be reasons for variation between the suburbs. The key to our question would be to tease out if any price differences are due to hurricane damage.

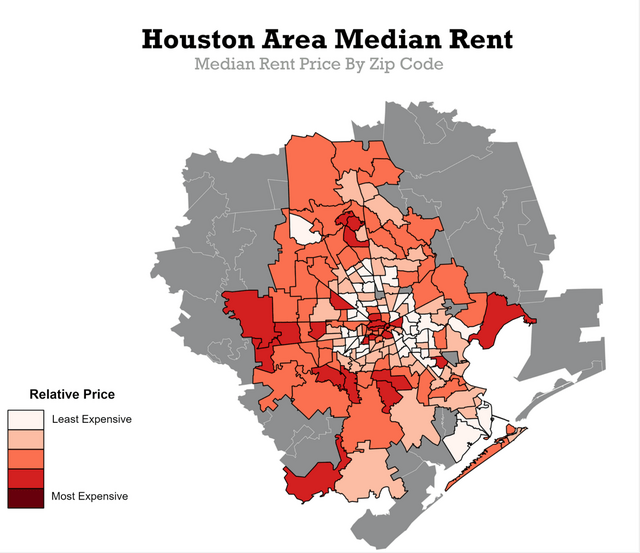

To start this line of analysis, we’ve mapped the median price for each zip code in the Houston area. The intensity of the color indicates cost of rent, with pricier areas being shaded darker.

Data Source: RentHop. Shapefile Source: City of Houston Geographic Information System (COHGIS)

From this we can see that in general, the most expensive areas are right in downtown and some of the wealthier suburbs.

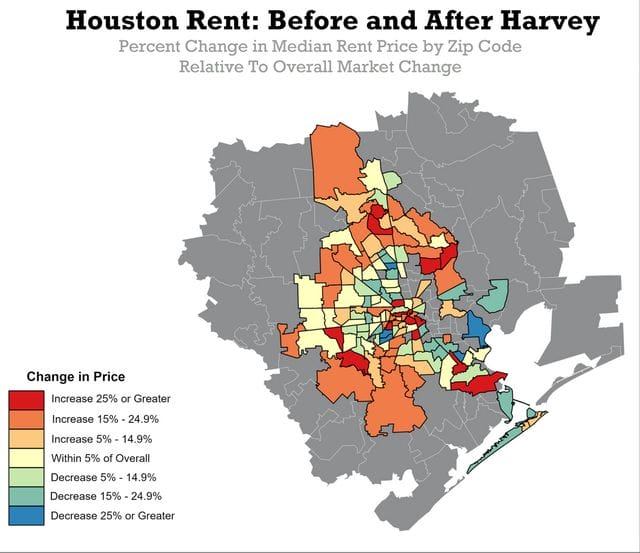

Now we want to see how all these prices in these zip codes generally changed after Harvey. To run this analysis, we grouped prices from 50 days before the hurricane and 50 days after and calculated the median for each time interval. We then found how much the prices changed relative to how the market changed overall. In the map below, zip codes that increased in price are in red, while those that decreased are in blue. The intensity of the color indicates the degree of change.

Data Source: RentHop; Dates compared Before Harvey: July 6, 2017 – August 25, 2017 After Harvey: August 26, 2017 – October 15, 2017

Shapefile Source: City of Houston Geographic Information System (COHGIS)

The largest price increases are concentrated in a few zip codes, several within the heart of downtown and others on the northern and western periphery. There are two factors likely working together to cause this pattern. Downtown Houston was had higher rents to start with, so some of this shift could be the continuation of the housing boom. Some of it though is possibly connected to the vast flooding in the area. Due to locations of reservoirs and floodplains, damage was extensive to the north and west of the city, near where we see some of our higher rent increases.

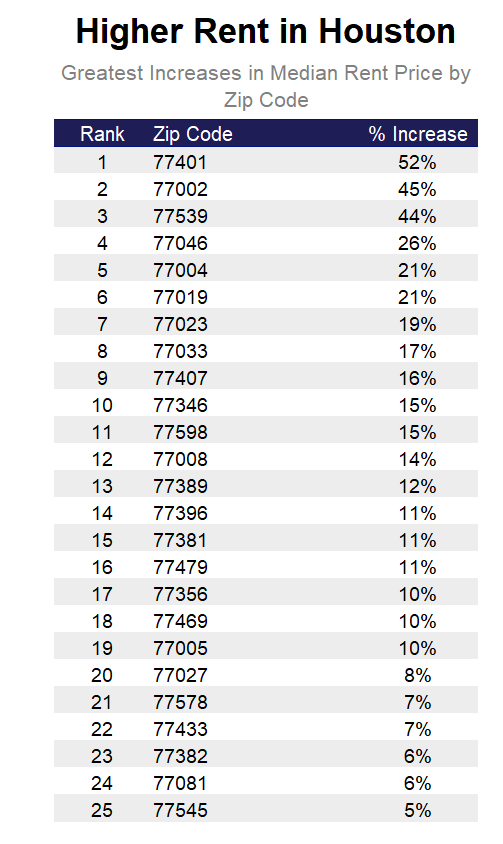

To see exactly how much some of these zip codes were impacted, we can list out those with the greatest increases.

Data Source: RentHop

We can see that, on initial inspection, 19 zip codes appear to meet the 10% price increase threshold for greater investigation by the state.

The largest change was in Bellaire, Texas, is a largely upper-middle class community about 10 miles southwest of Houston. Flooding here was extensive during the storm and some residents report past issues with flooding. It does seem plausible that in a community with generally more expensive housing, widespread damage could reduce the number of rentals and increase prices.

The other two top zip codes were in Downtown Houston, and Dickinson, a community between Galveston and Houston, which also faced flooding damage from Harvey.

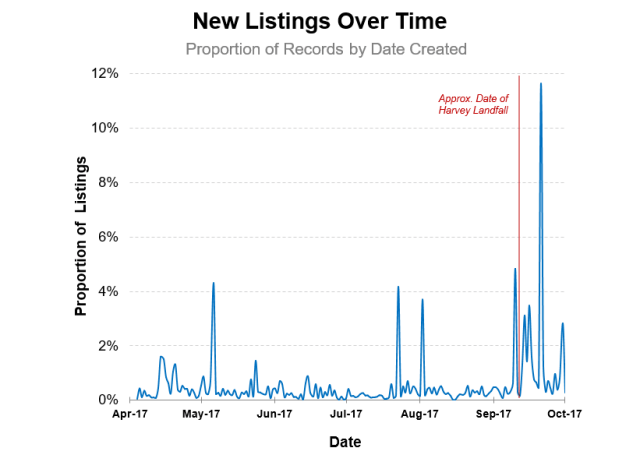

It is hard to investigate exactly what caused these price increases, but we can look into one factor that is related to price. The thought is, with the extensive damage, there are just fewer houses on the market. Market forces would push the price up in any case where supply is limited. But from what we are seeing, are there fewer homes available? We can plot how many rentals are listed by date and see if there’s any change over time.

Data Source: RentHop

Here we actually see the lumber of listings spike after the hurricane. Perhaps people are seeing an opportunity to rent out an extra room given the market or maybe tenants are leaving partially damaged apartments and they’re headed back onto the market. Whatever the cause, with an increase in listings, we would expect a price decrease.

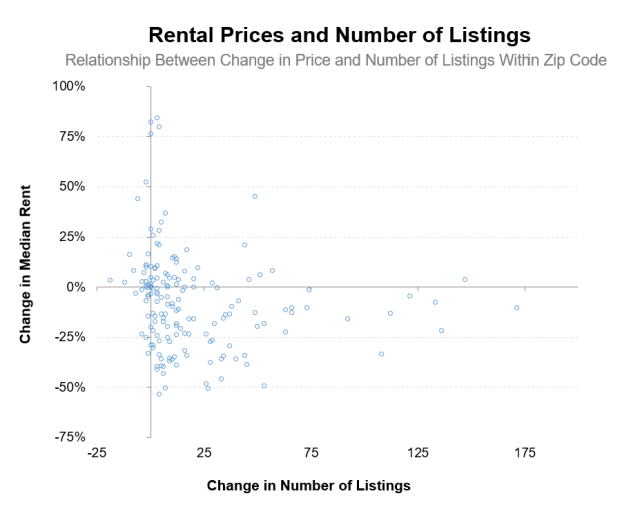

Is there any relationship with the number of listings and prices? For each zip code, we’ve plotted the change in price before and after the hurricane against the change in number of listed rentals.

Data Source: RentHop

In most zip codes we see an increase in the number of listings. Another noticeable trend is that in areas with more listings, the price is actually more often decreasing. In areas with price increases, there are typically few or a reduction in the number of new listings. This would support the conventional relationship that areas with more listings (a greater supply of housing) are cheaper. The bulk of the price increases are happening where there aren’t a lot of new rentals.

The ultimate question is whether all of this constitutes price gouging. While we did see a lot of interesting trends suggesting some types of rentals are more expensive, we do not have anything to suggest illegal price increases.This problem should be monitored vigilantly at the local level to ensure renters are protected. Hopefully, this provided some insight into the state of the Houston housing market in after Hurricane Harvey.

***

Note: If you’re a company that wants to work with Priceonomics to turn your data into great stories, learn more about the Priceonomics Data Studio.