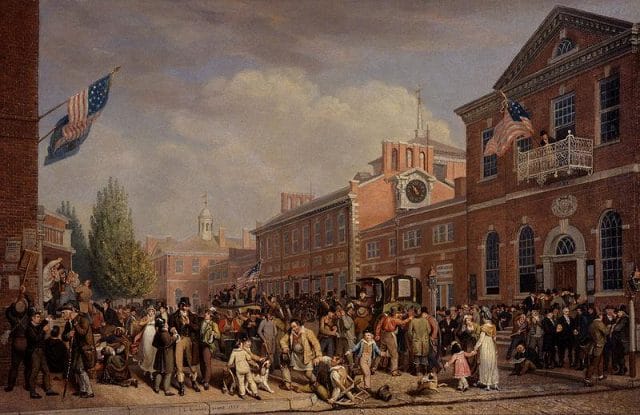

Election Scene by John Lewis Krimmel (1816)

When French aristocrat Alexis de Tocqueville surveyed the United States, he made an observation that would make any American newsperson swoon for the good old days of 1831. “Nothing is easier than to set up a newspaper,” he wrote, “as a small number of subscribers suffices to defray the expenses.”

Not so today. Despite having over 2 million subscribers, the New York Times faces scrutiny from investors who suspect its business model may no longer be viable. Papers without a global brand have bled money and jobs, and subscribers only provide one quarter of newspapers’ funding.

Contemporary analysis of newspapers’ (and journalism’s) woes usually focus on the impact of technology: newspapers lost their lucrative classifieds business to Craigslist, the ubiquity of online advertising options diminished the value of ads in newspapers and magazines, and blogs sprouted up and started recounting the results of journalists’ reporting without pounding the pavement themselves.

But during de Tocqueville’s visit to America in 1831, newspapers flourished not due to the absence of the Internet, but due to decisions made by the Founding Fathers. In 1792, Congress instructed the postal service to deliver newspapers at the “rock-bottom rate” of 1 cent to 1.5 cents. Two years later, Congress extended the same privileges to magazines and other periodicals.

Congress funded the Postal Service’s role as the gratuit delivery service for America’s news by setting higher rates for private letters and by subsidizing the service’s budget with treasury funds. For years, American leaders agreed that facilitating the spread of news was worth the collective expense. George Washington, who once made it clear that he would like to see all news delivered for free, wrote to a friend:

I entertain a high idea of the utility of periodical Publications: insomuch that I could heartily desire, copies of . . . Magazines, as well as common Gazettes, might spread through every city, town and village in America.

The Postal Service delivered newspapers and magazines for free or at highly subsidized rates for the first 100 years of the country’s history. The price of delivering news publications only really began to rise in 1917, due to the financial strain of World War I, and did not reach the actual cost of delivery until 1980. Even in 1951, the subsidized delivery of periodicals was a $200 million gift to America’s news industry.

This news subsidy contributed to a vibrant press that led de Tocqueville to remark that “In America there is scarcely a hamlet that has not its newspaper.” According to historian Charles Sellers, around the time of de Tocqueville’s visit in 1840, the United States had more newspapers than any other country.

Huffington Post, Circa 1840

One could conclude that the United States has a great tradition of public support for the press — a tradition that needs to be remembered and reinstituted as journalism undergoes what many refer to as a time of crisis. An 18th or 19th century Congressman might recommend as much to today’s politicians; as late as 1906, a representative of South Carolina waxed about the Postal Service’s subsidized, rural deliveries that it “has become a great university in which 36 million of our people receive their daily lessons from the newspapers and magazines of the country.”

Alexis de Tocqueville, however, would not agree. Although the Postal Service proudly quotes the Frenchman, whose book Democracy In America is now a classic text on early America, de Tocqueville reported the ubiquity of American news sources while trying to understand “the small influence of the American journals.” Far from describing a golden age of journalism, de Tocqueville was analyzing the smallness of the American press.

His arguments sound remarkably like contemporary criticism of blogs. And, in fact, a closer look reveals that the situation facing 19th century newssheets resembles that of today’s digital offerings.

Alexis de Tocqueville, who would be unlikely to invest in Buzzfeed if he were alive today. Photo credit: Wikimedia

Distributing news — then and now — is cheap and almost free. Just as sharing news on a blog or website allows anyone to reach a global audience at very little cost, the Post Office’s subsidies allowed newspapers and magazines to reach subscribers for almost nothing. The result in 1830 was the huge number of papers that de Tocqueville remarked on, just as today the result is a million different websites with journalistic aims ranging from food porn to news analysis.

The news environments also parallel each other in that filing a publication with news stories was almost as cheap in 1830 as it is today. Traditional news publications have loudly complained that bloggers steal their stories: a New Yorker or LA Times reporter can spend months on an exposé, and the Huffington Post will reap all the rewards by writing a short article that summarizes the findings and draws more readers than the original. In this way, digital news sources can share news at a very low cost. In 1830, newspapers did the same. The Postal Service allowed newspapers to send each other news and articles for free, which newspapers then published. Just as many blogs and digital sites “borrow” articles and scoops from traditional media, many smaller, 19th century papers filled as much as 85% of their pages with these “borrowed” articles.

The result is a distinctly modern media criticism voiced by a 19th century French aristocrat. Alexis de Tocqueville mirrors the viewpoint of a contemporary grizzled newspaper editor who pines for the days when everyone got their news from a single paper like the Wall Street Journal or Boston Globe: de Tocqueville writes that “the only way to neutralize the effect of the public journals is to multiply their number.” Like today’s innumerable online voices, America’s papers may have attacked and defended the government “in a thousand different ways,” but, as de Tocqueville writes, “they cannot form those great currents of opinion which sweep away the strongest of dikes.”

Worse, according to de Tocqueville, America’s early papers were like Buzzfeed and celebrity gossip sites, their pages filled with ads and “political intelligence or trivial anecdotes.” Only rarely, the Frenchman laments, could one find “a corner devoted to passionate discussion, like those which the journalists of France every day give to their readers.” Substitute the op-ed pages of elite publications for de Tocqueville’s native press, and you have a grumpy response to digital journalism and all those goddamned listicles.

And finally, Alexis de Tocqueville criticizes American journalists for trolling as much as critics accuse those bothersome bloggers at Gawker of doing. He writes:

The characteristics of the American journalist consist in an open and coarse appeal to the passions of his readers; he abandons principles to assail the characters of individuals, to track them into private life, and disclose all their weaknesses and vices.

The ad hominem personal attack is a staple of low quality blogs, where George Bush’s fratboy past or an entrepreneur’s foibles supplant criticism of policies or industries. And the charge that American journalists could only “kindle” existing passions (rather than create them or point them in the proper direction) parallels worries about the balkanizing effect of the Internet, which allows people to get news and analysis from sources that cherry pick facts to reaffirm their pre-existing beliefs rather than challenge them.

Despite the industry’s poor health, some leading figures in journalism argue that it is experiencing a “golden age.” The Internet and smartphones have lowered the barriers to entry to journalism and greatly expanded people’s access to the articles journalists write; a number of investors, including Jeff Bezos of Amazon, have poured money into digital news sources, gambling that they can thrive and profit in this new environment. Most journalists, however, worry that they’ll be too busy losing their jobs and cutting costs to write articles of value.

Alexis de Tocqueville’s observations fall in line with the second camp, as he saw America’s innumerable cheap journals as of poor quality. In his view, journalism would be better served in conditions like famous vineyards: Winemakers plant grapes in soil of poor quality, as the stress improves the flavor of the grapes that survive. Grapes grown in fertile soil, like journalism in an environment where it is easy to produce and share, cannot compare.

Yet de Tocqueville, who greatly admired America and its democratic project, also offers — from a distance of 180 years — a hopeful note about the value of digital journalism. He writes:

Although the press is limited to these resources, its influence in America is immense. It causes political life to circulate through all the parts of that vast territory. Its eye is constantly open to detect the secret springs of political designs, and to summon the leaders of all parties in turn to the bar of public opinion… Each separate journal exercises but little authority; but the power of the periodical press is second only to that of the people.

This post was written by Alex Mayyasi. Follow him on Twitter here or Google Plus. To get occasional notifications when we write blog posts, sign up for our email list.