Americans are not happy with their politicians. Eight in ten are displeased with Washington, 81% disapprove of the job Congress is doing, and President Obama’s approval rating stands at 45%.

Increased partisanship is a common reason given for DC’s dysfunction. The perverse influence of money is another. For those blaming the latter, Harvard professor Larry Lessig recently gave a very crystallized argument for why money’s perverse influence is systemic.

He describes America as having two elections:

“The United States has two elections. One a voting election, where citizens get to select the candidates who will ultimately govern. But the other is a money election, where the candidates who wish to run in the voting election raise the money they need to compete… the candidates don’t necessarily need to win the money election. But they must do extremely well.”

In the fundraising election, according to Lessig, only 50,000-150,000 Americans contribute enough money to be noticed by politicians. These are people like Sheldon Adelson, the casino mogul who gave $70 million to Republicans in the 2012 elections.

Corruption in Congress, Lessig argues, arises from the fact that members of Congress must spend so much of their time attending to the needs of the Adelsons of America in order to do well in the fundraising election:

“For members of Congress and candidates for Congress spend anywhere between 30% and 70% of their time raising money from this tiny, tiny slice of us. Think of a rat in a Skinner box, learning which buttons to push to get pellets of food, and you have a pretty good sense of the life of a congressman: a constant attention to what must be done to raise money, and to raise money not from all of us, but from the tiniest slice of the 1% of us.”

Lessig believes that until the rules governing fundraising for elections change so that candidates are not constantly courting this small donor base, Washington’s corruption and lack of attention to Main Street issues will continue.

We would add another segment of America whose voice is unduly heightened – the type of people who actually vote in primaries.

In presidential and congressional races, the Republican and Democratic parties hold elections to select a candidate for the general election. This has no basis in the Constitution; it is an invention of the parties. So, again, we have a two election system in which one empowers one specific group of people.

In the 2008 presidential primaries, voter turnout averaged only 26.1% across states. (We used 2008 over 2012 as no party had an incumbent in 2008.) In contrast, turnout for the general election was 63.5%.

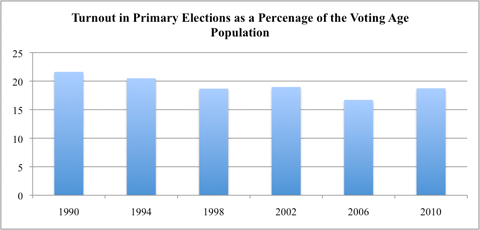

The situation can be much more extreme in the case of primaries for congressional seats. Average turnout for elections during a year without a presidential race is under 20%. The majority of primaries are “closed” so that only registered republicans or democrats can vote in them.

The Center for Voting and Democracy affirms the common perception that relatively few people turn out for these primaries: “Congressional primaries have similarly low turnout; for example, turnout was only 7 percent in a recent Tennessee primary, and was only 3 percent for a U.S. Senate primary in Texas.”

Why is this a problem? Because the people that vote in primaries tend to be the least compromising and most partisan voters, according to critics of the primary system.

We have one election in which the richest 100,000 Americans vote, one election in which the most partisan 20% of Americans vote, and one election in which all Americans can actually vote. How could a system like that ever turn out well?

This post was written by Alex Mayyasi. Follow him on Twitter or Google Plus.