Editors note: This guest post was written by Jim Pagels.

Antitrust laws exist to prevent businesses from conspiring to artificially limit demand, set prices, or restrict pay. Earlier this year, a U.S. District Court forced Apple, Google, Intel and Adobe to pay $325 million in a class action lawsuit for agreeing not to poach each other’s employees. There is one industry, though, where wide-scale collusion is not only legal, but universal: professional sports. Salary caps, which exist in most leagues, are one of several mechanisms that allow a club of billionaire sports team owners to collectively control and suppress the wages of millionaire young athletes. How did this come about, and are they effective? Could leagues function without them? And under what pretenses can billionaire owners argue that they need to collectively suppress wages?

The key difference between sports and other industries is that competition is the product that leagues sell. If teams could purchase victories or if the Vegas odds always favored the same teams, then the value of that competition would decline. In other words, New York Yankees tickets would not be nearly as valuable if they played against Little League teams. (Although the first game would be entertaining.)

For this reason, leagues argue that they must sustain some degree of parity between their teams, and they claim to accomplish this through revenue sharing, entry-level player drafts, and, most of all, salary caps — limits on the amount of money teams can spend on players.

The History of Salary Caps

Salary caps are a relatively new phenomenon. Before the introduction of free agency in the 1980s, many leagues, most notably Major League Baseball, operated under the “reserve clause,” which prohibited players from negotiating with other teams, even after the conclusion of a contract. Players challenge this clause in the 1970s, and owners offered many of the same arguments then that they do today about salary caps:

“…owners of sports teams developed the argument that, whatever the consequences of the reserve clause on players’ salaries, it was needed to preserve competitive balance. Owners argued that free agency would allow the richest teams to acquire a disproportionate share of the playing talent in the league. Competitive balance would be destroyed, driving weaker franchises out of business.”

By the 1980s, free agency was in vogue, and with this, owners soon introduced a more modern labor control too: salary caps. Today, the NFL and NHL both have hard caps, which means that no team can exceed a certain spending limit. Under the NBA’s soft cap, teams can exceed the cap, but only to retain their own players — a clause known as the “Larry Bird Exception” as the Boston Celtics used this rule to retain Bird for his entire career. The MLB only has a (very forgiving) luxury tax — a threshold above which teams must pay a certain percentage in penalty for every dollar they spend over the limit. In the 11-year history of the tax, only five teams have ever paid, with the Yankees’ payments constituting 95% of that total.

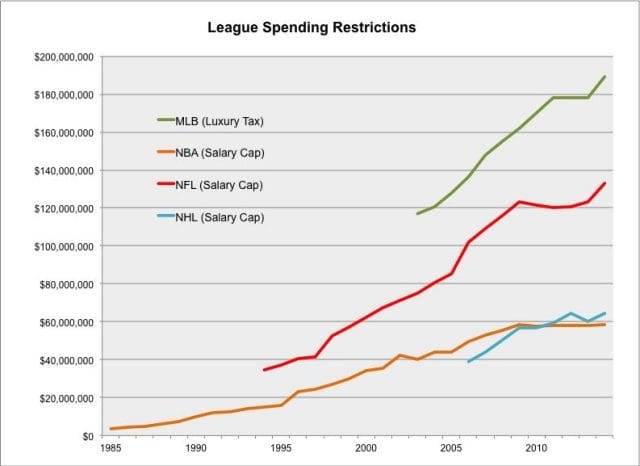

As sports have become more lucrative, salary caps have increased:

*Due to an ongoing Collective Bargaining Agreement negotiation, the 2011 NFL season was uncapped. In this chart, 2011 is simply represented as the average between 2010 and 2012.

**The NBA figure is misleading, since there are so many exceptions that over two-thirds of the league exceeds the soft cap.

Today, salary caps are controversial. Its critics often argue on the grounds of antitrust, but the existence depends on whether you view a league’s franchises as a single, unified entity or a collection of individual firms. This classification came up in the 1922 Baltimore Federal Baseball Club v. National League case, in which a unanimous ruling held baseball exempt from antitrust laws. Nearly a century later, the courts delivered a different decision in the 2010 American Needle v. NFL Supreme Court case, which declared that the NFL’s collective apparel licensing was in fact subject to examination under the Sherman Antitrust Act.

The Case for Salary Caps

Salary cap proponents argue that caps are effective and necessary. They give poorer, small-market teams a chance to compete, and this competitive balance draws in fans and benefits the league as a whole.

A substantial body of academic literature supports this claim. A 2011 paper in Economic Inquiry that investigated salary caps, salary floors, and revenue sharing found that “the effect on club profits, player salaries, and competitive balance crucially depends on the mix of these policy tools.” Another 2011 University of Alabama paper that focused on baseball argued that the sport has a severe competitive balance issue that negatively affects fan interest. Other studies have shown that salary caps have effectively promoted competitive balance and concluded that forbidding leagues from operating as a single entity would hurt revenues.

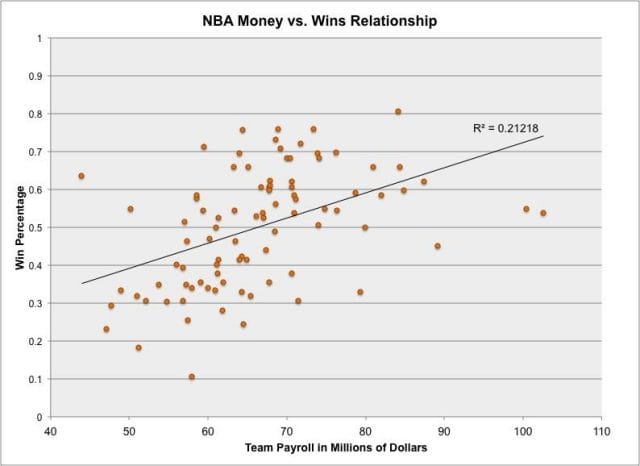

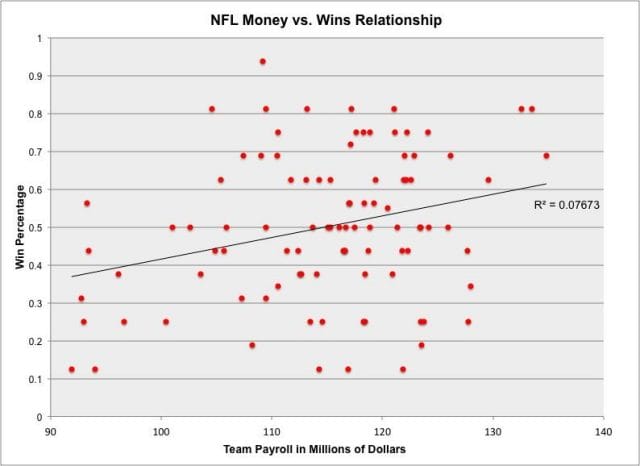

The case for salary caps is strongest for sports in which the correlation between money and wins is relatively strong. There have been countless analytic studies on this subject, and they have largely shown that these strong relationships occur in sports with a) small year-to-year variation in player performance, which makes it easier to accurately spend money and b) a large season sample size so that inferior (often poorer) teams are weeded out.

Here’s an example of the money vs. performance relationship in the NFL (a league with narrow talent variation, a 16-game season, and single game playoffs) and the NBA (a league with wide talent variation, an 82-game season, and 7-game playoff series).

As expected, the NFL — which still has variation in spending despite a hard cap — has a rather weak money vs. performance correlation compared to the NBA. (The correlation in the NBA would be much stronger if not for a maximum salary on individual players, which artificially limits their value and allows General Managers to assemble super-teams under the cap.) The stronger NBA correlation suggests that in the absence of spending restrictions, teams might gain a significant edge, which could cause overall league revenues — and in turn player salaries — to decline as a select few teams in large markets or with wealthy owners dominate each and every year.

There’s historical precedent for this concern: In 1884, the Union Associated baseball league folded after a single season when the St. Louis Maroons ran away with first place by 21 games. Similarly, the All-America Football Conference folded after four years in the late 1940s. The Cleveland Browns tore through the league, losing only three games in four years — a performance so dominant that it literally destroyed the league.

Cap proponents also point to modern examples like the English Premier League (EPL), where a lack of spending restrictions has led to incredible disparity between payrolls. The wealthiest clubs buy up the best players and dominate; only four teams (Manchester United, Manchester City, Chelsea, and Arsenal) have won the league since 1995. (Those four teams also largely dominate the 2nd- and 3rd-place finishes.)

With this extreme inequality, the EPL reportedly took in over $5 billion in revenue last year — half that of the NFL — with much of that revenue concentrated among the top 4-5 teams while mid- and smaller-tier clubs languished. However, the Union of European Football Associations recently announced a set of regulations known as Financial Fair Play to balance spending among the top teams. Deloitte describes the new protocols effect in the 23rd edition of the Annual Review of Football Finance:

The signs are that most clubs are adopting a more financially robust and balanced approach to the way they run their businesses, and they must continue down this path if they are to safeguard the long-term financial health of the game.

Along these lines, cap proponents often argue that financial restraint is necessary to keep franchises — and their valuable brand identities — afloat for generations. In largely restriction-free English soccer, there is a vast graveyard of defunct clubs, many of which spent themselves into oblivion. The sink-or-swim spending atmosphere of the Football League Championship — the second-tier league below the EPL — has led nine of its 24 teams to employ player payrolls greater than that of their revenues, endangering long-term stability. Comparatively, in the four major American sports, no team has folded since the Dallas Texans closed shop back in 1952.

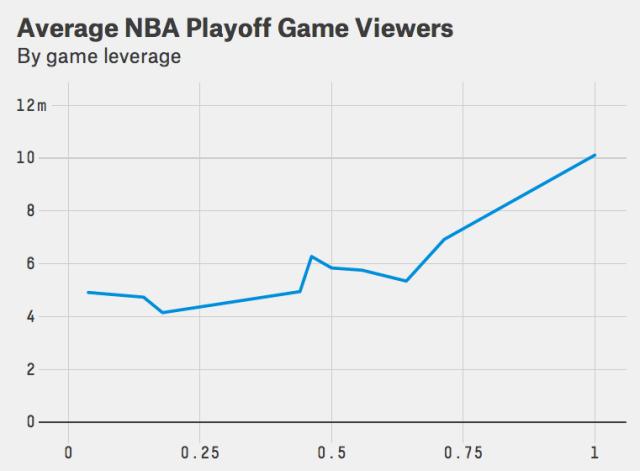

Cap proponents also claim that parity is necessary to grow fan bases across the country, and the numbers back this up. A 2009 article in the Journal of Sports Economics noted that “winning is an important determinant of attendance” for all 12 MLB teams in the study, and randomness and unexpected outcomes — common in leagues with great parity — attract eyeballs. While those opposed to caps argue that fans watch any game with the slightest uncertainty in its outcome, this ignores the larger picture. Yes, any individual game will always have some uncertainty, but postseason races or playoff series can easily be all but decided, and the data suggests that this inevitability turns away fans.

NBA playoff game TV ratings spike when the series is close, but they are far lower when one team takes a near-decisive lead. Here’s the average TV rating by leverage, a metric that measures the importance of a playoff game in swinging a series, for all 250 playoff games from 2011-2013:

Running a regression on this data, controlling for year, time, market size, round, and TV channel, shows game number in the series and leverage — both indicators of a close matchup — to be highly indicative of ratings. Similarly, MLB teams that fall out of contention early see their attendance languish in the second half of the season. Sure, the battle may be always in doubt, but if the war is all but decided, viewers appear to tune out.

The Case Against Salary Caps

Those against salary caps argue that a group of firms shouldn’t have the power to collude against labor wages and that salary caps do not enforce league parity, but instead merely tamp down costs for wealthy teams. In other words, caps are discounts for billionaires.

It’s not too difficult to see the logic behind this. In a completely free market, high-revenue teams would bid each other up to high figures for elite players, but salary caps serve as an insurance policy against each other. In uncapped baseball, Miguel Cabrera, worth only 5-7 extra wins per season (out of 162), can sign a 10-year, $292 million contract. Meanwhile, LeBron James’s value to his team is many multiples of Cabrera.

However, for the majority of his prime, LeBron has made roughly half what Cabrera now earns, and the four-time NBA MVP has taken notice. (It’s worth noting that the average NBA salary is actually far greater than that of MLB, but much of this is simply due to splitting revenue between far fewer players in basketball. Also, this extreme devaluation of NBA star talent is in some extent due to the overall league salary cap, but more so due to the individual maximum player salary, an extremely constricting clause that dramatically decreases parity as it facilitates the creation of super teams by allowing them to fit multiple salary-controlled superstars under the cap—something teams could never do without such measures. LeBron isn’t teaming up with Dwyane Wade and Chris Bosh if he can go make $45 million a year playing in Phoenix or Denver.)

Salary cap opponents also argue that spending restrictions are ineffective — if not outright detrimental — at achieving their intended goal of parity. David Berri, author of The Wages of Wins, finds that the implementation of caps and luxury taxes in the NBA, NHL, NHL, and MLB had a statistically insignificant impact on parity. He also calculates that perfect balance in the MLB would only result in a 15% increase in attendance. Similarly, a 2011 paper in the Journal for Economic Educators found that a cap in the NBA would actually hurt competitive balance, most likely due to exemptions which restrict player movement, and showed that revenue sharing is a much more effective way to institute parity. (The effects of revenue sharing on profit maximization and parity enforcement has been highly debated.)

At the furthest extreme, one study by antitrust economist Andy Schwartz noted that with all monetary incentives perfectly equal (at zero), college football severely obstructs the Coase theorem, which states that labor will find its way to locations in which it has the greatest utility, and has inequality on par with that found in the EPL. Other critics contend that salary caps and revenue sharing coddle underperforming franchises. Since owners know that losing seasons won’t put them out of business, these policies reduce the incentive to win. Rather than the EPL’s “sink-or-swim” format, American sports have more of a “swim-or-repeatedly tread water” approach.

Those against caps also note that playoffs encourage competitive balance in terms of championship totals. Elimination games or series spur randomness and frequently allow inferior (often low-revenue) teams to prevail in small sample sizes.

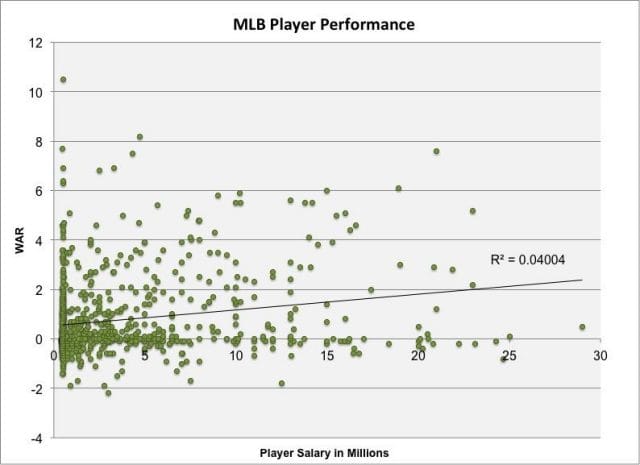

The need for spending limits will vary by sport, but the strongest case against a cap comes in the only game without one: baseball. Due to the sport’s inherent randomness — even over the course of a 162-game season — it’s extremely difficult to accurately spend money on player talent. In 2013, the correlation between player salary and performance was nearly zero:

While the concept of winning an “unfair game” was popularized by Michael Lewis’s 2003 book, Moneyball, lack of large payroll certainly hasn’t been too big a detriment for many teams. In fact, recent articles in The Hardball Times and Freakonomics show that the relationship between money and wins has decreased over time.

Are Caps Fair?

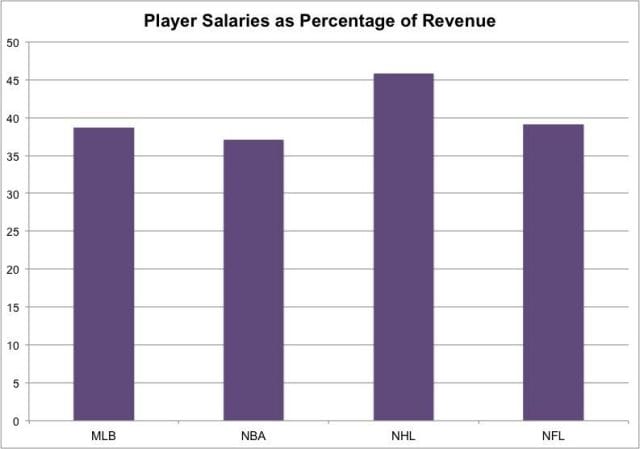

In negotiating salary caps, most leagues split mandatory sport-specific revenue roughly 50-50 between owners and players. In recent years, players have agreed to accept a smaller slice of the pie. In both the most recent NBA and NHL labor negotiations, players went from receiving 57% of basketball- and hockey-related income to 50% while NFL players went from a 50/50 split to 47%. When factoring in total league revenues, players’ shares are slightly smaller, but roughly equal across sports:

*Interestingly, the two leagues with hard caps distribute the highest percentage of total revenue in player payroll—a finding backed by academic research.

If caps or luxury taxes were removed, would players earn more? A 2007 Southern Economic Journal study found that revenue redistribution lowered MLB salaries by roughly 22% and had little effect on parity. In the NBA, the effect is likely stronger as over a dozen teams regularly brush up against an extremely punitive luxury tax and jockey for strategic revenue-sharing positions lower on the payroll rankings.

A 50/50 split may seem fair at first glance, but a number of arguments make the case that owners receive far too much of the pie.

The players’ declining share of revenue resulted from owners playing hardball in recent lockouts, as players realized that holding out for a higher share of revenues was not worth missing part of the season. After all, any additional revenue players could earn in the future would be negated by lost wages in the present. This provided owners with a huge bargaining advantage. While the players have limited career windows to earn money in the league, the owners have their entire lives and can afford to use this time advantage as leverage.

Owners also have the advantage of being the only show in town, as no viable alternative leagues exist to draw players. Leagues with competition have not had as much success implementing caps. The English Premiership rugby league installed a cap in 1999, but many of its star players moved to Japan and France, where spending was not restricted.

Back to LeBron for a moment: The NBA superstar, who currently makes $20.6 million per year in the NBA, famously expressed interest in playing in Europe should someone offer a $50 million annual salary. The idea was not outlandish. James’s salary is limited by restrictions on maximum player salaries, there are some very wealthy European owners, and his true financial worth is estimated at between $40 and $50 million, even under the cap. No deal materialized, so James continues to play in the United States.

(Staying in America, however, would probably always be LeBron’s best option. While the four-time MVP has made only $126 million in salary over his career, he has also made $326 million in endorsements by playing in the most famous basketball league on the planet. It would be difficult to match that figure while playing in a little-known European league. One could argue that these endorsement opportunities are so profitable due to relative parity, which drives the NBA’s universal popularity.)

Owners always bring up annual revenues and costs when negotiating a salary cap, but only focusing on those figures is extremely shortsighted. When you consider that teams in every sport are rapidly gaining value, franchises could actually lose quite a bit of money each year, and owners would still make large capital gains to recoup those losses.

One could also ask whether sports franchises should turn a profit at all, given their status as luxury toys for billionaires. Owning a professional sports team is not like owning an insurance company; it’s more like owning a rare painting or a Ferrari — a status symbol. If the NBA approached a group of wealthy businessmen and said, “Ignore profits and just focus on this: You’ll become an instant celebrity, sit courtside at every game, and hang out with superstar athletes. How much would you pay for that lifestyle?” that would surely fetch a high price.

Malcolm Gladwell discusses this subject in a 2011 Grantland story, in which he notes that economists call these extra perks of owning something like sports team “psychic benefits”:

Forbes magazine annually estimates the value of every professional franchise, based on standard financial metrics like operating expenses, ticket sales, revenue, and physical assets like stadiums. When sports teams change hands, however, the actual sales price is invariably higher. Forbes valued the Detroit Pistons at $360 million. They just sold for $420 million. Forbes valued the Wizards at $322 million. They just sold for $551 million. Forbes said that the Warriors were worth $363 million. They just sold for $450 million. There are a number of reasons why the Forbes number is consistently too low. The simplest is that Forbes is evaluating franchises strictly as businesses. But they are being bought by people who care passionately about sports — and the $90 million premium that the Warriors’ new owners were willing to pay represents the psychic benefit of owning a sports team.

With these these points in mind, you can make a strong case that teams should not only lose money each year, but actually lose quite a bit of money. So while salary caps are hotly contested, we can offer some answers to the questions that motivated this article.

Are salary caps necessary? It depends on the sport, with randomness and season length being primary factors. In baseball, where greater financial resources is no guarantee of success, the MLB has done fine in terms of parity with limited restrictions. If the NBA got rid of all spending controls, however, deep-pocketed teams in New York and L.A. would inevitably dominate.

Are salary caps fair? Almost never — at least at current levels. The government allows American sports leagues to maintain a national monopoly in a way allowed in almost no other industry, and it accepts policies like salary caps that would normally run afoul of antitrust laws. Part of the onus on fighting this status quo lies on players’ unions to bring up psychic benefits at the CBA negotiating table. Another may involve wealthy investors starting their own leagues with more favorable player salaries — or perhaps, as one paper suggests, the government forcibly splitting up leagues as it once split up oil, aluminum, and tobacco cartels.

Having said that, the evidence suggests that some form of spending restrictions or revenue sharing is probably best for the quality and financial interests of the game. Sports owners, however, have arguable abused that leniency by extracting far too high a share of league revenues, even as there’s a line around the block of wealthy investors ready to throw down vast sums for sports franchises the moment they come up for sale to acquire the immense capital gains, annual profits, and perhaps most importantly, status and lifestyle that come with them.

That’s one more telling detail about the current state of affairs: Hundreds of players come and go every year, but owners cling on to franchises for life and routinely pass them down to their children after death. While there have been high-profile sales of the Los Angeles Clippers, Buffalo Bills, and Milwaukee Bucks in recent years, it’s rare teams actually hit the open market. Owners know how great a deal they’re getting – they get to own a fun toy that also appreciates in value. That’s not something they’re going to part with anytime soon.

This guest post was written by Jim Pagels. Follow him on Twitter here.