![]()

Blue Moon Brewing Company — the producer of the much-loved Belgian-style wheat beer — has all the aesthetic trimmings of a small, artsy brand.

On the company’s website, hand-painted posters of small towns, farmers’ markets, and open fields dance across the screen in a colorful montage. The top of each page is adorned with wood panels; the bottom of each page is a faux-burlap sack. A “Meet Our Brewers” section elaborates on the “down-to-earth” micro-brewery expertise of its team members.

Most fancifully, Blue Moon Brewing Company relates its founding story — a tale that makes it sound like a tiny, authentic operation that started in a garage:

“At Blue Moon Brewing Company, we believe brewing is an art. And it’s been that way since our head brewmaster and founder, Keith Villa, first created Blue Moon Belgian White Belgian-Style Wheat Ale back in 1995 in downtown Denver, Colorado.

…Everything we do flows from our artistic approach to brewing. We carefully select quality ingredients to go into each of our beers. Then we spend time making test batches until we arrive at a balanced, flavorful beer that we all enjoy drinking. And that is why we say our beers, and everything we do, are Artfully Crafted.”

But a look beyond the company’s artsy advertisements and “craft beer” claims reveals an entirely different story — a story chock full of misleading labels, consumer deception, and sneaky marketing by a big-name beer brand.

While Blue Moon passes itself off as a craft beer, it is, in reality, a product of MillerCoors, the second-largest brewing conglomerate in the United States.

How Coors Frankensteined a “Craft” Beer

Despite America’s gradual decline in per capita beer consumption, “craft” breweries have experienced tremendous growth.

The Brewers Association, a widely-recognized organization whose purpose is to “promote and protect American craft brewers,” essentially wrote the constitution for what qualifies as a “craft” beer. By definition, they declare that a craft beer must fit within the following guidelines:

* An American craft brewer must be small, independent and traditional.

* Its annual production must be 6 million barrels of beer or less.

* Less than 25% of the craft brewery must be owned or controlled (or equivalent economic interest) by an alcoholic beverage industry member that is not itself a craft brewer.

“Craft brewers maintain integrity by what they brew,” adds the Association, “and [they maintain] their general independence, free from a substantial interest by a non-craft brewer.”

From 1989 to 1999, the number craft breweries in the U.S. rose from 246 to 1,564; after a brief period of stagnation, a second boom in 2007 saw craft breweries explode in popularity. Today, there some 2,768 of these breweries in operation in the U.S.

Noticing this rising craft beer trend, Coors, one of America’s largest brewers, wanted to get in on the action. Keith Villa, a worker at the company’s Coors Field brewery in Denver, was tasked with developing a beer to compete in the emerging craft market. In 1995, Coors released the product of Villa’s labor: Blue Moon Belgian White — a cloudy wheat beer with a hint of orange.

But Coors had a problem: their massive brand, and its association with shitty, watered-down beers, did not mesh well with its attempt to pass off Blue Moon as a quality craft beer. According to Coors’ then-CEO, Blue Moon had an identity problem:

“[Our consumers] think that all products brewed by a particular brewery taste the same, and their mind is closed. We have proved that we…can brew great craft beer. But the consumer says that doesn’t really compute.”

His solution was obfuscation. “The specialty products will not say ‘Coors,’” he candidly told a sociologist in 1995. “We want them disassociated from the Coors family.”

The motive of his rationale is simple: studies on organizational behavior show that, as consumers, we believe smaller companies produce higher quality products. Often, we favor products that we perceive to be “made by traditional methods” (ie. craft beers) because these products generate “status:” they allow us to openly display our sophisticated palates and refinement. If we knew that a fine brew like Blue Moon came from the same company that made Coors Light, we wouldn’t as readily consume it.

How Blue Moon Misleads Its Consumers

Over time, Blue Moon’s ownership has gotten a bit more complex. In 2005, Coors merged with Canada’s Molson, to form the Molson Coors Brewing Company. Two years later, this company partnered with another goliath, SABMiller, to form the joint venture MillerCoors.

Today, MillerCoors employs a variety of tactics to ensure that: 1. Its customers are uninformed about the true origins of Blue Moon, and 2. It is able to pass off Blue Moon as a craft beer, and, as such, keep it relevant in the eyes of its craft-crazed consumers.

According to the stipulations laid out by the Brewers Association, Blue Moon is far from being considered a craft beer, and MillerCoors knows it — yet they have still marketed it to consumers as a craft beer.

As craft beers really started to take off in 2010, MillerCoors realized it had to do everything it could to conceal its association with Blue Moon, and make it seem as if it were an artisan brew. That August, the conglomerate created “Tenth and Blake Beer Company,” and used it as a subsidiary of sorts for their “craft” beers, Blue Moon included. Then, MillerCoors went about branding their new company as a craft beer enthusiast’s wet dream. Here’s the “About Us” blurb from its Facebook page:

“Tenth and Blake is building the beer drinker’s beer company! We’re made up of passionate brewers and merchants of the world’s finest specialty brews, celebrating the joy of beer with our customers and consumers.”

In order to sell Blue Moon as an artsy, hand-crafted, small batch beer, the big-name brand decided it best to exclude any mention of its name from packaging. On bottles sold in the U.S., the beer was marketed as an exotic Belgian beer, with labels harping on the brew’s “artistic approach” and unique blend of flavors:

In the U.S., Blue Moon labels read, “Belgian-Style Wheat Ale”

Bottles in the U.K. went even further. Not only did they omit the beer’s Coors origin, but the the label championed it as a result of “old-world, handcrafted tradition,” and explicitly listed it as a “North American Craft Beer.”

“[We’re] just a bunch of friends having fun making great beer,” reads the story on the back. “What’s not to love about that?”

In the U.K., Blue Moon labels read “North American Craft Beer”

But both countries’ products — and most of Blue Moon’s products world-wide, for that matter — share one thing in common: nowhere on the packaging is there any indication that the beer is a product of MillerCoors, the second-largest brewer in the United States.

The Brewers Association, which fights for the rights of craft brewers, took issue with this in a statement a few years ago:

“The large, multinational brewers appear to be deliberately attempting to blur the lines between their crafty, craft-like beers and true craft beers from today’s small and independent brewers. We call for transparency in brand ownership and for information to be clearly presented in a way that allows beer drinkers to make an informed choice about who brewed the beer they are drinking.”

By obfuscating its brand name on products like Blue Moon, Coors is violating the consumer’s right to know who he is supporting, and where his beverage comes from.

Charles Bamforth, a professor of brewing sciences at UC Davis and one of the world’s foremost authorities on beer, finds this off-putting.

“I believe that there should be a clear statement on any beer’s label that shows the name of the parent brewing company,” he tells Priceonomics. “If a company is proud of itself and also wants to let a beer be judged on its merits, then I see no reason why that company should not clearly boast of its provenance.”

At the same time, Bamforth cedes that MillerCoors has a defensible reason behind its actions. “There are many people who automatically rubbish the products of the [major breweries] no matter how good they are; the mentality of such critics is equally as crazy,” he adds. “The drinker should judge those beers on their qualities, not on the label.”

This is precisely what Anheuser-Busch, America’s largest brewing company, used to do. When they released Shock Top Belgian White in 2006 to compete with Blue Moon, they similarly marketed it as a craft beer — despite having a market share of nearly 50% on the brewing industry. But unlike MillerCoors, Anheuser-Busch openly (and proudly) donned its name on the product:

Early Shock Top Belgian White labels clearly listed “Anheuser-Busch” as the beer’s parent company

In an interview with a market researcher, an Anheuser-Busch spokesperson elucidated an entirely different strategy to that of MillerCoors:

“Our name is on our beers right now. We are who we are, and we’re certainly not going to try to fool beer drinkers or hide behind another name. That’s the worst thing you can do. We made a conscious decision about that because we think we brew very high quality beers. We should be proud of that and we are”

Of course, this attitude didn’t last long. A few years later, when a research team found that “30 percent of [craft beer consumers] would not buy an Anheuser-Busch product,” the company withdrew any indication of its name from its website and labeling. Not even the product’s fine print identifies the mega brand behind it.

Plenty of other “craft” brews are equally deceptive: Red Hook, Kona, Leinenkugel, Magic Hat, and Goose Island — each revered as a small, independent brand — all downplay their ties with mega breweries.

***

In this world of deceptive “craft” beers, Blue Moon is heads and shoulders above its competitors.

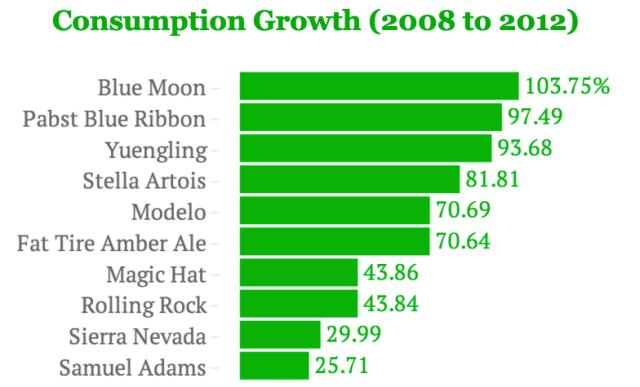

MillerCoors’ 2014 annual report boasts of Blue Moon’s “73 consecutive quarters of growth” — a Herculean feat for any company, nonetheless a brewery. Today, Blue Moon sells more than two million barrels of beer each year, which is equal to 15% of all craft beer sales in the U.S. The company’s rising sales numbers place them as the fastest-growing beer in the country:

Consumption figures specific to the U.S.; Data via Quartz

At the end of the day, despite Blue Moon’s flagrant disregard for transparency, beer critics still tout it as a decent brew. Beverage reviewer Beer Advocate gives it a 77/100. Brothers Jason and Todd Alström, who run the popular site, rate it as an 87, or “very good,” but add a disclaimer: “Everyone who buys this beer who [we] know did not even have a clue that it was a Coors product.”

Blue Moon seems to thrive, in part, due to its fans’ obliviousness — and MillerCoors’ strategy of deception has paid off. No matter what it tastes like, it’s still important for consumers to realize that the only thing “crafty” about Blue Moon is its marketing.

![]()

This post was written by Zachary Crockett. You can follow him on Twitter here.

To get occasional notifications when we write blog posts, please sign up for our email list.