Over the past four years, the rock band Phish has generated over $120 million in ticket sales, handily surpassing more well known artists like Radiohead, The Black Keys, and One Direction. Since their start 30 years ago, Phish has consistently been one of the most popular and lucrative touring acts in America, generating well over a quarter billion dollars in ticket sales.

Yet, by other measures, the band isn’t popular at all. Only one of their original albums has ever made the Billboard top 10 rankings. None of their 883 songs has ever become a popular hit on the radio. They’ve made only one music video to promote a song, and it was mocked mercilessly by Beavis and Butthead on MTV.

If the traditional band business model is to generate hype through the media and radio airplay, and then monetize that hype through album sales and tours, Phish doesn’t fit the model at all. For a band of their stature, their album sales are miniscule and radio airplay non-existent. And so when the “music business” cratered in the 1990s because of file-sharing and radio’s importance declined because of the internet, Phish remained unaffected and profitable as ever.

Phish doesn’t make money by selling music. They make money by selling live music, and that, it turns out, is a more durable business model. This wasn’t some brilliant pre-calculated strategy by the band or its managers; it’s the business model that sprung forth from the kind of music the band makes. The band developed the kernel of this musical style during their first five years when they played almost exclusively in bars in Burlington, Vermont, and slowly, but organically, grew their audience.

During this period they maniacally focused on improving the quality of their music through intense practice and frequent gigs at bars. And while at first these gigs were relatively unsuccessful, over time their audiences grew, the band started to make money, and then, after five years of obscurity, they were profitable before anyone in the music industry knew who the hell they were. And with profitability came the freedom to make music on their terms.

In the parlance of startup language, Phish bootstrapped their business rather than seeking support from institutional players like record labels, talent agencies, and concert promoters. And that’s made all the difference.

10,000 Hours of Jamming

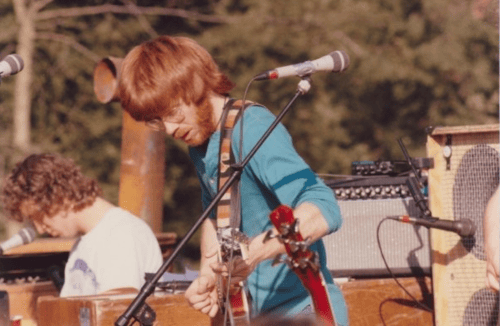

The band Phish got its start in 1983 at the University of Vermont (UVM) where Trey Anastasio, Jon Fishman, and Mike Gordon were all students. Page McConnell, a student at nearby Goddard College, joined the band two years later. Since then, that’s been the core band – Anastasio on lead vocals and guitar, Gordon on bass guitar, Fishman on the drums, and McConnell on keyboard / piano.

A popular theory these days for explaining “genius” is Malcolm Gladwell’s theory of 10,000 hours. In his book Outliers, Gladwell posits that natural talent is a necessary, but not sufficient, condition for achieving greatness in a given field. What is also required is putting in thousands of hours of “deliberate practice” to achieve virtuoso status in fields ranging from software development (Bill Gates) to physics (Robert Oppenheimer).

The band Phish appears to be another case in support of Gladwell’s theory that deliberate practice at an early age leads to “outlier” performance. Anastasio, the band’s frontman, started playing the guitar at the age of seven and was in serious bands by middle school. Fishman, the drummer, started playing at the age of five. McConnell started playing the piano at the age of four. By the time they entered college, not only were they accomplished musicians, but what united them was their preference for practicing music over attending class.

From the band’s early days until the late 1990s, they showed a near fanatical obsession with practice. Fishman, the drummer, remembers college:

“Basically I locked myself in a room for three years and played drums and went to band practice.”

The same level of intensity was brought to band practice. Gordon, the bassist, relates an eight-hour, chemically-assisted, practice session that was not atypical:

“Trey used to take fresh chocolate and vanilla and maple syrup and all these natural ingredients and make four small cups of hot chocolate that had a half-ounce of pot in them. … [So] we started this jam session and it ended up going for eight hours.”

Even as the band became popular a decade later, they practiced together using highly analytical listening exercises. Phish biographer Parke Puterbaugh explains one of these exercises:

The best known was called “Including Your Own Hey.” These exercises, which formed a large part of their practice regimen from 1990 through 1995, are not so easy to explain but important for understanding how Phish could maintain a seemingly telepathic chemistry in concert.

“‘Hey’ means we’re locked in,” explained Anastasio. “The idea is don’t play anything complicated; just pick a hole and fill it.” They explored different elements of music—tempo, timbre, dynamics, harmonics—within the “hey” regimen.

While today Phish is well known as a “jam band” that improvises on stage, it wasn’t until 1993, 10 years after their formation, that the band really unveiled this skill according to the band archivist Kevin Shapiro:

“Before 1993, it had seemed to be a very practiced, concise show that flowed real fast and didn’t necessarily have any huge improvisational moments. All of a sudden there were huge improvisational moments everywhere.”

Before Phish achieved any success, they worked hard at their craft. At the peak of their success, they practiced just as hard, if not harder. Later, they would abandon these regular practice sessions, which could either be seen as a cause or a symptom of the problems that lead to the band’s breakup in 2004.

The Slow, Linear Rise of Phish

“Burlington is an excellent womb for a band. It’s relatively easy to get a gig, you get paid decently, and it’s not a cut-throat situation at all.”

– Jon Fishman, Drummer

Phish’s first gig was playing an ROTC Ball in late 1983 before they had even settled on their eventual band name. If you’ve ever heard them play, you already know that their music probably wasn’t the best choice for future army officers and their dates to boogie to. Eventually, the band was drowned out when someone put on Michael Jackson’s “Thriller” and the evening was resurrected – from the ball attendees’ perspective at least.

After a brief detour when Anastasio was suspended from the UVM for sending a human heart and hand through the US Postal Service as a prank, most of the band transferred to Goddard College where they could pursue a self-directed study of music. During this period, they started to regularly play gigs at local bars.

Phish’s first regular bar gig was weekdays at 5 PM. The few people who came were their friends. After the ROTC dance debacle, they couldn’t even get booked for campus gigs, let alone real music venues. But they stuck with playing bars at off-peak hours and eventually the audience swelled modestly from their friends to their friends and friends of friends.

Phish biographer Parke Puterbaugh comments:

This all worked to Phish’s advantage, as they weren’t swamped by success but experienced a slow, steady climb, during which they nurtured their craft in an environment where they gained a following one fan at a time. They gradually cultivated a varied audience of college students and hipsters from Burlington and environs.

At this time, Phish started to display the organic growth in their fanbase that would characterize the rest of their careers – they would win over fans one at a time through their live performances and those fans would recruit their friends to come to the next show.

Eventually, Phish was invited to play at a more popular local bar called Nectars. At Nectars they moved from the the upstairs stage to the main stage. Band frontman Anastasio remembers:

“Usually there wouldn’t be that many people at the beginning of the night. People would come and go, and it would just kind of swell. Eventually, it started getting really packed, which is why we had to stop playing there. But for a long time, it wasn’t.”

Eventually they started to get a lot of stage time at the more popular bars in Vermont. During this time, they honed what would become their signature talent – keeping a live audience enthralled, dancing, and having fun all night. Drummer Fishman describes the freedom to experiment they had during this time:

“For five years we had Nectar’s and other places around town to play from nine until two in the morning,” recalled Fishman. “We’d get three-night stands, so we didn’t even have to move our equipment. Basically, the crowd was our guinea pig. We’d have up to five hours to do whatever the hell we wanted.”

A fan reminisces what it was like to hear Phish in those days:

“They sort of sucked when we first started seeing them,” admitted Tom Baggott, a Phish fan and acquaintance. “They were getting it together. They were sort of sloppy, you know, but that was the fun of it. That was the magic of it. It was like there was a big joke going on and all the early Phish fans knew the punch line—which was that this was gonna be something big.”

These insanely loyal fans not only dragged their friends to shows, but also started taping the shows and passing out the tapes to friends. Rather than squelch this “piracy,” the band encouraged it. Not only did it provide great marketing that lead to larger show attendance, but it helped develop an obsessive fanbase that would later desire to collect everything about the Phish experience: rare tapes, concert experiences, official albums, and merchandise.

After years of honing their craft on their homecourt of Burlington, Vermont, they got their big break in 1989. Or rather, they manufactured their big break. The Paradise Night Club, a 650 seat venue in Boston that was a proving ground for rock bands, refused to book the band. By this time, Phish had two buddies serving as their business managers who were responsible for booking gigs. The managers took a gamble and decided to rent out The Paradise and take the risk of selling the tickets themselves.

With the help of their now diehard fans, Phish sold out all 650 seats. Many of their fans trekked down from Burlington. One fan organized two buses from Burlington that brought almost a hundred fans. The rabid fan base that Phish had cultivated from its 5 years of gigging in Burlington paid off big time.

After Phish sold out The Paradise, doors were open to them. Phish biographer Parke Puterbaugh relates the scene in the Boston music industry:

Beth Montuori Rowles recalled the reaction at Don Law’s office the next day: “Jody Goodman, who was the club booker at the time, was like, ‘Does anybody know who this band Phish is? They sold out The Paradise last night. How did that happen? I’ve never even heard of them before. They’re from Vermont. What is this? They sold the place out!’

“All of a sudden it was like the radar’s on them. The next time Phish played in Boston, the Don Law Company promoted it. They wanted a piece of it. End of story.”

Phish started touring in progressively larger venues. Still, the growth was never exponential or Bieber-esque. In an interview with High Times, Anastasio reflects:

“If you look at the whole 17 years of Phish, it was an exact, angular rise. It was at the point where our manager used to be able to predict how many tickets we were going to sell in a given town based on how many times we had played there previously. Every time we played, it got a little bit bigger, and it kept getting a little bit bigger.”

Shortly after selling out The Paradise, despite not a single music label or management company knowing their name, the band was profitable. Rather than rushing to put out a Top 40 hit, the band could focus on doing more of what was already earning them money, making music and touring.

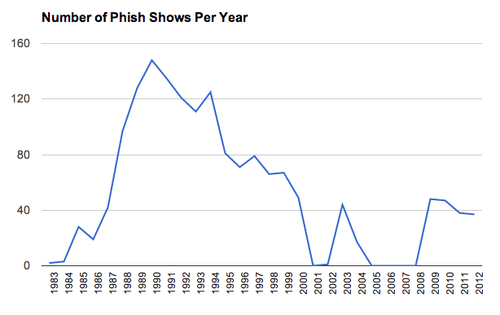

From here on out, the band rapidly accelerated the number of shows, performing well over a hundred times a year all over the country. By the end of 1994, they sold out the Boston Garden for a New Years Eve show. They were cemented as a big time band that could sell out arenas, bring tens of thousands of fans to remote weekend festivals, and generate tens of millions of dollars in ticket sales per year. They were bona fide rock stars.

From here on out, the band rapidly accelerated the number of shows, performing well over a hundred times a year all over the country. By the end of 1994, they sold out the Boston Garden for a New Years Eve show. They were cemented as a big time band that could sell out arenas, bring tens of thousands of fans to remote weekend festivals, and generate tens of millions of dollars in ticket sales per year. They were bona fide rock stars.

Why Do People Like Phish?

So what exactly is this form of music that Phish learned how to play in Burlington, Vermont, that has inspired such a loyal following?

Among people that don’t frequently listen to Phish, it can be hard to ascertain why the band is so popular. But if you spend any time sampling the YouTube videos of the band’s live performances, you’ll see ample evidence that people love Phish.

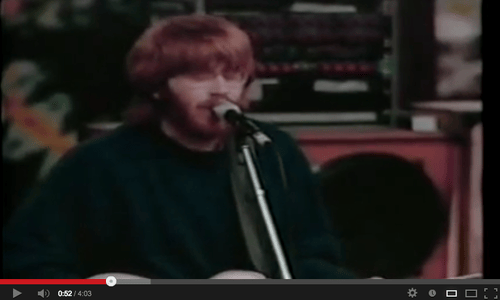

In this relatively early video, you can get a sense of the effect the band has on its audience. Even as the band plays a slow melody, the audience raucously bounces around, captivated by every note.

So, why do people love Phish? Partly because the band is comprised of immensely skilled musicians. Their years of intense practice means that not only are their individual skills strong, but as a collective entity, they know how to play with each other. They are skilled musicians, but listeners disdain virtuoso musicians every day. The band’s technical skill cannot completely explain their rampant popularity.

The first part of the answer is that Phish’s live performances are built around an interaction between the band and the audience. That’s the product that Phish sells, the interplay between the band and audience. The audience is an integral part of the show.

When the audience hears the right cue from the guitar, the fans know to chant “Wilson,” and they know that Wilson is the antagonist from Anastasio’s senior thesis, an epic musical composition. When the song “You Enjoy Myself” comes on, the audience roars with delight when the guitarists jam while jumping on trampolines, even though they know it’s coming. As you listen to live recordings of Phish, you notice that for every note the band plays, the audience provides a response that guides the band. It’s the back and forth between the audience and the band that creates the live musical production.

Remember, it took a decade of practice before Phish really started improvising on stage at a grand scale. If going to a U2 concert is like purchasing a mass produced print, a Phish show is like buying a unique painting. The band has never played the same set list twice and you never know when a ten minute song could morph into a thirty minute improvised jam.

Next, Phish is an immersive world that fans can get lost in, not unlike Tolkien’s Lord of the Rings trilogy. There is a mythology about the band and its shows and history. Just as a fan of Lord of the Rings may have memorized Frodo’s family tree, a Phish fan knows what Gamehendge and Rhombus are.

Fans don’t merely go see Phish, they collect Phish experiences. They track the number of concerts they’ve gone to, which songs from the band’s catalogue they’ve heard, and which venues they still need to see Phish perform at. Due to the bands improvised and varied sets, Phish fans constantly collect new experiences. Popular shows like Gamehoist, Big Cypress, Clifford Ball, and Salt Lake City 1998 have taken on near mythological proportions.

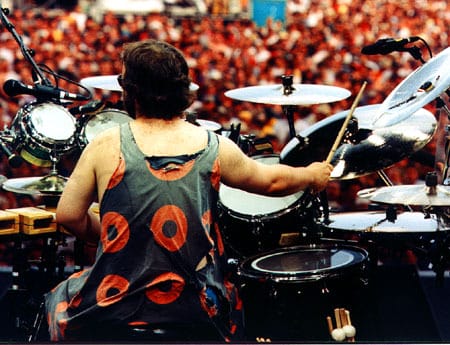

Finally, it seems that Phish puts on a show. The band might be flying through an arena playing on a giant hot dog, playing an eight hour set till sunrise, or pretending that Tom Hanks is on stage with them. There is a whimsy and unpredictability to their shows. The drummer occasionally plays a vacuum cleaner on stage, and almost always wears a woman’s dress while performing (except when he performs naked). At any Phish show, something strange, amazing, or unique could happen. For the diehard fan, the fear of missing out on one of these shows drives them to try to attend every one.

It’s worth noting that all of these reasons why people do like Phish also completely explain why other people don’t like Phish.

Almost none of the experience of watching Phish live translates over to their recorded music. Their studio recorded albums, without the excitement and energy of the audience, sound comparatively sad and lonely; almost like the difference between eating a great meal with a group of friends versus all by yourself. Same food, different experience. And while the music may demonstrate technical prowess, the complicated, layered 30-minute jams performed by the band don’t translate well to the radio.

Some people in this world love Phish more than you can possibly understand. This author’s wife is one of those people. As a compromise, one Phish song was selected to be performed during the dancing portion of this author’s wedding reception. When that song came on, half the dance floor cleared out. They stood to the side and stared with befuddlement as the other half of the attendees danced to a slow, strange, and seemingly undanceable song. The Phish fans were in rapture because their favorite band was blasting through the speakers and they knew that if Tweezer was performed now, that Tweezer Reprise would make an appearance at the after party.

The Business Model

From 1989 onward, before the band had even been signed to a record label, Phish was profitable from live touring. Keep in mind, they had been at it for 5 years, scraping by on gigs in Burlington’s bars. During that time, they developed their most valuable asset, the ability to enthrall fans through live music.

Because Phish achieved financial independence before the music industry even recognized them, they more or less could do whatever they wanted. The took their early profits and started their own management company, Dionysian Productions. They hired a staff of 40+ people that handled their elaborate stage productions and back office operations. They built their own merchandise company so that their shirts and other paraphernalia reflected the band’s artistic sensibilities. They even started a mail order ticket company so that fans could send them money orders and buy tickets directly from the band.

In 1991, they signed with a major record label, Elektra (owned by Warner). As they had the leverage in the relationship, Phish never really had a lot of conflict with their label about artistic control. They didn’t need money from album sales because they made money from live shows, so they never had to dilute their artistic vision to get radio airplay and sell albums. Of course, the result of this artistic freedom was that they never sold albums at a rate commensurate with their popularity.

Perhaps more so than any major musical artist today, the Phish business model is derived from having hard core fans of its live music. When Madonna sells out arenas across the country, she’s selling tickets to her various fans that live everywhere. When Phish sells out arenas or festivals across the country, it’s because the same die-hard fans fly across the country to see the band. In the rare instances where fans don’t make the trek and the shows don’t sell out, the band punishes the no-shows by performing a particularly epic set. In a forum where ardent Phish fans compare how much money they had spent on going to see the band, the answers were in the tens of thousands of dollars.

So while Phish undoubtedly has fewer fans than Madonna, the ticket revenue per fan is way higher because fans loyally attend multiple shows. Not since the Grateful Dead has a band built a following as loyal as Phish. And like the Grateful Dead, Phish merchandising is a big business as fans gobble up Phish t-shirts, baby-onesies, and hats.

When file sharing and piracy ravaged the music industry, Phish was insulated because their primary business was selling access to live music, not recorded music. In fact, the band was able to take advantage of the trends of digital downloads and streaming. They bundled digital downloads of live performances with ticket sales so that everyone who attended a show could download its broadcast the next day. And those that can’t attend shows live can pay to stream the performance from Phish’s website. While technological advancements made it harder for some artists to profit from their work, if anything, it made it easier for Phish to do so.

The Rise and Fall and Rise of Phish

In 2004, Phish broke up. There are a lot of reasons given: rampant drug use by the band, the financial pressure of having over 40 people on payroll that needed to be paid whether the band was touring or not, or that after 20+ years of a grueling tour schedule, the band had simply run its course.

In an interview with Charlie Rose right after the breakup, frontman Anastasio gave a compelling reason for the breakup – the passion for making great music together was no longer there. Anastasio tells Rose, how once felt about the music:

“You know, it was like — the only thought was about the show. I mean, I used to lock myself in my hotel room, as soon as the concert was over. For years, I would run back to my hotel room and start working on the set for the next night. And even though there wasn`t really a set list, there kind of was. Like I knew what was going on. And I was working and working and working, you know, oh my God, for hours, ripping pieces of papers up, books, you know, and I`d like you to practice them, come on, guys, everybody in the practice room. And then hours before the show, songs we hadn`t played in a while — I mean, it was just like a heavy work ethic until we got on stage. And then it was just a celebration.”

The band that practiced so diligently for most of its tenure stopped practicing together in 1998. By 2004, fans began commenting that the musical quality of the band was declining. What could have been a triumphant final show in Coventry, Vermont, was a disaster. Not only did rain and mud wreak havoc on the weekend, but the band’s music performance was universally panned. The musical geniuses of Phish went out with a whimper.

Phish Inc started to become a more bloated, drug-polluted entity precisely when their desire to make great music together was waning. And so, it was time to call it quits.

Until, that is, it was time to call it unquits. The band reunited in 2009 for a three-night show in Hampton, Virginia. The announcement sent a shockwave through the Phish community and an even greater shock wave through the Ticketmaster ordering system. The heavy traffic crashed the site. In the five years they were broken up, the band cleaned up, streamlined their staff, and gradually rebuilt the personal relationships between the band members. And so, in a testament to the strength of the following they built, they reunited and have generated over $120 million in the four subsequent years.

Conclusion

The members of Phish knew they wanted to make music since they were little kids. And they worked at it harder than anyone else. They have generated hundreds of millions of dollars in concert sales, but their roots were humble and their growth was slow. They spent five years in the relative obscurity of Burlington, Vermont, perfecting their craft. And through that process, they learned how to entertain a live audience. That turned out to make all the difference.

Every time Phish played, their audience grew only slightly. But devoted fans evangelized their music and the word spread. Growth was slow, but it compounded until suddenly the band could sell out 650 seat clubs. And then one day they could sell out Madison Square Garden four nights in a row. And some of those fans attended the show all four nights and the the ones who didn’t wished they had.

Phish worked long and hard to become great musicians and performers. This has lead to a durable business model built around live concerts. Could another band replicate their success? Maybe. But how many of them would quit before realizing how good they could be? Or would the band be discovered by the music industry too early and release a major label record that flops?

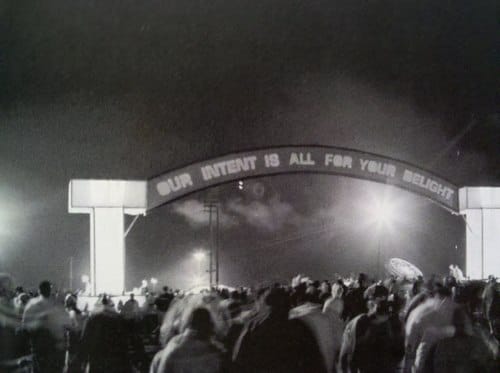

At a Phish show in 2003, the crowd was greeted by a giant banner proclaiming, “Our Intent Is All for Your Delight.” It’s Phish’s pure devotion to music that makes them beloved of their fans. It’s also what ended up making them gob fulls of money, so that worked out nicely.

This post was written by Rohin Dhar. Follow him on Twitter here or Google. After researching this story and finding out how hard Phish works at their craft, he’s finally agreed to attend one of their shows with his wife this summer. If you want to read more about Phish, this biography is excellent.