On March 4, an editor at The Atlantic asked Nate Thayer if he could write a condensed version of a story he’d published on NKNews about Dennis Rodman’s visit to North Korea. Thayer expressed interest. The editor responded:

Thanks for responding. Maybe by the end of the week? 1,200 words? We unfortunately can’t pay you for it, but we do reach 13 million readers a month. I understand if that’s not a workable arrangement for you, I just wanted to see if you were interested.

Thayer decided that he’d had enough of his writing being undervalued:

I am a professional journalist who has made my living by writing for 25 years and am not in the habit of giving my services for free to for profit media outlets so they can make money by using my work and efforts by removing my ability to pay my bills and feed my children.

He then published the email exchange on his blog. In the firestorm that followed on Twitter, a senior Atlantic editor, Alexis Madrigal, published an article in response. He titled it “A Day in the Life of a Digital Editor, 2013.” While he expresses sympathy for the plight of Thayer and the thousands of freelancers working “for peanuts,” he makes the case that this is the reality of journalism in the digital age:

Then the digital transition came. The ad market, on which we all depend, started going haywire. Advertisers didn’t have to buy The Atlantic. They could buy ads on networks that had dropped a cookie on people visiting The Atlantic. They could snatch our audience right out from underneath us. And besides, who knew how well online ads worked anyway? I mean, who knows how well any ads work at all? But convention had established that print ads were a thing people paid X amount for, and digital ads became something people paid 0.10X for.

In other words (of his):

So far, there isn’t a single model for our kind of magazine that appears to work.

Hard Choices

Madrigal presents the following strategies that a digital editor can take:

1. Write a lot of original pieces yourself. (Pro: Awesome. Con: Hard, slow.)

2. Take partner content. (Pro: Content! Con: It’s someone else’s content.)

3. Find people who are willing to write for a small amount of money. (Pro: Maybe good. Con: Often bad.)

4. Find people who are willing to write for no money. (Pro: Free. Con: Crapshoot.)

5. Aggregate like a mug. (Pro: Can put smartest stuff on blog. Con: No one will link to it.)

6. Rewrite press releases so they look like original content. (Pro: Content. Con: You suck.)

He then focuses on strategies three and four to explain why editors cannot pay a good wage for online content. It’s a fascinating look behind the choices faced by a struggling industry, and he offers authoritative data to back it up.

However, his presentation of data is hard for outsiders to follow. He jumps from example to example, once describing an editor with a $1,000 monthly budget to spend on freelancers, but without explaining how large a site may have a budget that size or what explicit benchmark that editor would need to hit with his $1,000.

Therefore, we decided to crunch the numbers ourselves to see if news sites can pay decent rates for online content.

By The Numbers

The Atlantic, like most news sites, does not have online subscriptions. Digital advertising is the sole major revenue source. According to Madrigal, the number of unique visitors is essentially the only metric that matters for hitting advertising numbers.

So, we’ll look at how much it would cost to hit The Atlantic’s 13.4 million visitors per month exclusively by paying journalists for original content. Of course editors use the other strategies listed above, but running the numbers for purely original content will shed light on the problems faced by journalists writing original stories.

Here is what Madrigal says on the number of visitors an article will bring to The Atlantic website:

While the top six or seven viral hits might make up 15-20 percent of a given month’s traffic, the falloff after that is steep. And once you’re out of the top 20 or 30 stories, a really, really successful story is only driving 0.5 percent or less of a place like The Atlantic‘s monthly traffic. But that’s the best-case scenario. In most cases, even great reported stories will fizzle, not spark. They will bring in 1,000 or 3,000 or 5,000 or 10,000 visitors. You’d need thousands of these to make a big site go.

Following this logic, let’s say that the 30 most viral articles drive 25% of the month’s traffic. That means The Atlantic needs to bring in another 10 million visitors from its other articles. If we say each article averages 5,000 visitors (to take the midpoint of Madrigal’s provided range), that means an additional 2,010 articles or blog posts for a total of 2,040 articles a month.

Paying a dollar per word has long been a conventional solid rate in journalism (despite inflation), and Madrigal cites it as such. Given this decent freelance rate, how much would it cost to produce all 2,040 articles?

To reiterate: in reality many of these posts will come from strategies 1, 2, 5, and 6. They’ll be aggregations of good content or posts written by staffers that summarize another site’s article with some additional analysis. But we are looking at the feasibility of a journalists’ utopia: filling the entire site with original content from real reporters. (Although arguably it’s not a utopia, just what journalism used to more or less look like, plus a website and tweeting.)

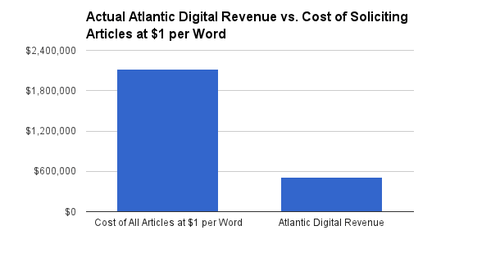

To get a representative word count per online article for The Atlantic, we took the average word count of the top 3 stories under each of the 9 sections on TheAtlantic.com. We calculated an average of 1,042 words per article. Multiply that by 2,040 articles a month and you get 2,125,680 words a month. At $1 per word, that means soliciting original content to meet your 13.4 million visitor traffic goal costs $2,125,680 per month!

If we compare this to The Atlantic’s actual monthly revenue from digital advertising in 2010 – roughly $6.1 million annually or just over half a million dollars per month – then The Atlantic can’t even come close to covering the costs of paying good wages for online content.

How much could The Atlantic pay writers for content with their digital ad revenue? Twenty-four cents a word. At 24 cents per word the digital revenue just covers the cost of paying writers. Of course, that doesn’t account for other costs: web hosting, editorial staff, tech staff, rent, and so on. So a site like The Atlantic would have to pay even less than 24 cents per word to break even online.

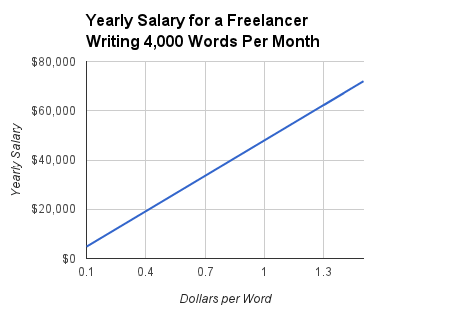

Thayer complained that contributing his writing for free wouldn’t “pay my bills and feed my children.” How about 24 cents per word?

Not likely. Twenty-four cents a word means $480 for a 2,000 word feature requiring 1-2 weeks of interviews, research, writing, and editing. Let’s use the maximum average word count a freelancer can produce from the American Society of Journalists and Authors (pdf) of 4,000 words per month. (This strikes us as low, but in addition to the time spent researching, writing, and editing, a freelancer has to actively seek out assignments and work around unfamiliear workflows – a staff writer could produce more.) Twenty-four cents a word comes out to a lousy annual salary of $11,520. Earning a salary of $40,000 would require an impossible production rate of 13,889 words per month.

As an award-winning journalist being asked to work for free, Thayer has good reason to be frustrated. (Although he might not given all the evidence suggesting that he plagiarized the North Korea story.) But the numbers do support Madrigal’s point.

Conclusion

Online editors at large news sites simply cannot afford to fill their site with original content and pay journalists well for their reporting. Given their current revenue model (ads), sites must take advantage of the abundance of free content on the web to cheaply write and aggregate blog posts to drive traffic. The Atlantic has done so quite successfully, and has a team of over 50 journalists devoted exclusively to its online presence.

Unfortunately, as a number of commentators pointed out, the new breed of journalist that curates content and writes stories based on online research leaves less room for original reporting – at least online. So many people are willing to write for free (scholars and politicians looking for exposure, young kids looking for a break) that “if you run a magazine and you’re *not* asking people to write for free, you’re doing it wrong.”

Further, as another journalist points out, the Atlantic editor’s only mistake was to ask Thayer to write a condensed version of his story. She could have simply written a quick article with block quotes from Thayer’s piece. That’s how online journalism is done today.

Digital editors can’t fill their sites with original content and pay for it. Journalists shouldn’t hate the player, they should hate the game.

This post was written by Alex Mayyasi. Follow him on Twitter here or Google.

Editors note: Occasionally The Atlantic republishes Priceonomics blog posts. We like the increased exposure.