“I have developed…an unenviable celebrity.”

~ Charles Babbage

![]()

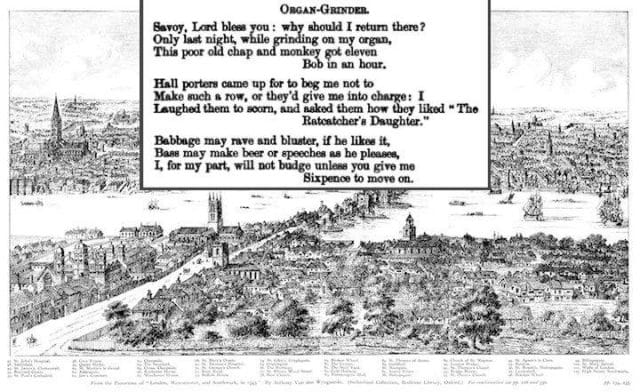

Street musicians really pissed off Charles Babbage.

“The great encouragers of street music belong chiefly to the lower classes of society,” he wrote in a not-isolated example of looking down his nose at people. He pointed a finger at the taverns. Such carousing caused the city’s less savory elements to get out of hand. London’s masses should spend their time doing something besides disturbing the peace with horns and organ grinders.

“It not infrequently gives rise to a dance by little ragged urchins, and sometimes by intoxicated men, who occasionally accompany the noise with their own discordant voices,” he wrote. In short, street music “destroys the time and the energies of all the intellectual classes of society by its continual interruptions of their pursuits.”

He wanted them banned. He needed to focus. He may not have been one of London’s friendliest faces, but he was certainly one of its greatest minds. After all, he was trying to construct the world’s first computer.

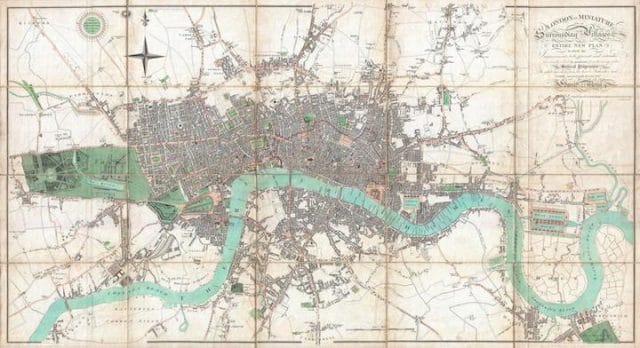

The king’s sonic highway

In the early 1800s, the Industrial Revolution forced Englanders to the cities as employment shifted from farmland to factories. Municipalities weren’t necessarily ready for the influx. People lived on top of each other, in tight apartments with thin walls. Metal carriage wheels ground on cobblestone. Kids played games on the sidewalks. Street vendors pushed their carts and shouted to attract business. Throw in the factories, and the clanging, ringing, smacking and bells and whistles — it was all a hurricane over London’s soundscape.

And as geography lecturer Dr Paul Simpson of Plymouth University points out:

“Technological advances in sound amplification and recording led to the ability to mechanically reproduce sounds beyond their initial taking place and/or makes previously imperceptible sounds audible…The clarity and definition of the pre-industrial soundscape really became a disorientating and indistinct noisescape.”

Victorian London was just loud.

Sound takes a real hold on our brains. We can change our gaze to avoid words or pictures. We can stop touching something. We can hold our noses. But you can’t selectively not-hear sound waves. And music cuts deeply. Melody heightens emotions and feelings, like love. Some researchers suspect — but certainly haven’t proven — that humans sang to one another before we started talking. Those tone detection mechanisms are buried deep in the brain.

And street musicians weren’t just innocent artists. Buskers were notorious (as some still are today) for planting themselves outside restaurants and stores, blaring noise, holding the soundscape hostage until someone forked over a few coins so they’d move on. But even for the honest artists, Babbage argued that people can’t walk into a public area and build a building — why should they be able to walk into a public area and fill it with noise?

“I have spared neither expense nor personal trouble in endeavouring to put a stop to this nuisance,” he noted.

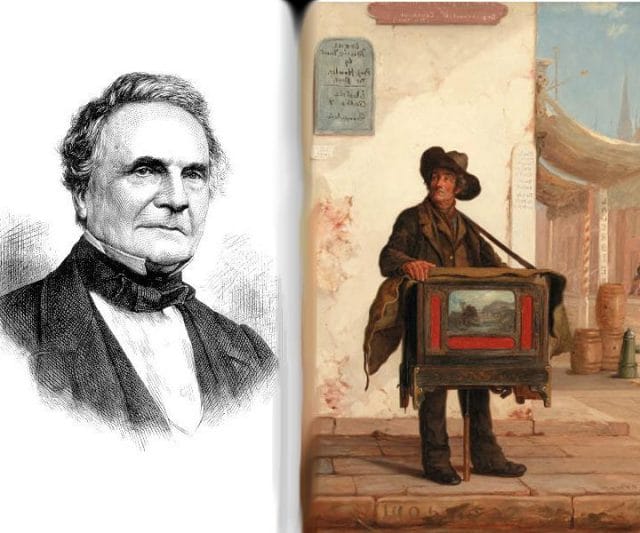

Making a different engine

The son of a wealthy banker, Babbage was a curious child whose family provided financial support for his studies and inventive pursuits into adulthood. The Lucasian mathematics professor at Cambridge from 1828 to 1839, a position held by Isaac Newton and Stephen Hawking, he was popular within high society London, known for advancements in cryptology and co-founding the Analytical Society, which worked to reform the mathematics Newton had taught. But his crowning achievement was designing three computational engines.

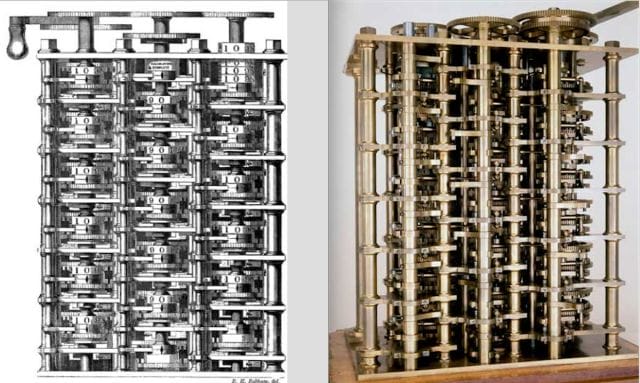

In 1821 he began blueprinting the first version of a “Difference Engine” — basically a calculator. Doron Swade, curator at the Computer History Museum and Babbage authority, notes that the Difference Engine was needed because people still made critical errors when calculating large sums, like for maritime tables where mistakes caused shipwrecks. Babbage did finish a portion of it that still works today, but the overall construction of the machine stalled in 1832.

Babbage’s attention then shifted to the “Analytical Engine”, a machine with many of the features of a modern computer. As The Computer History Museum describes:

It was programmable using punched cards, an idea borrowed from the Jacquard loom used for weaving complex patterns in textiles. The Engine had a ‘Store’ where numbers and intermediate results could be held, and a separate ‘Mill’ where the arithmetic processing was performed. It had an internal repertoire of the four arithmetical functions and could perform direct multiplication and division. It was also capable of functions for which we have modern names: conditional branching, looping (iteration), microprogramming, parallel processing, iteration, latching, polling, and pulse-shaping, amongst others, though Babbage nowhere used these terms. It had a variety of outputs including hardcopy printout, punched cards, graph plotting and the automatic production of stereotypes – trays of soft material into which results were impressed that could be used as molds for making printing plates.

Babbage worked closely with Ada Lovelace — often considered the world’s first programmer — to build out the capabilities for the Analytical Machine. But by the 1840s, he had again moved on to a third machine, an improved Difference Engine (No. 2). This version would work with thirty-one digit numbers and tabulate polynomials to the seventh order. The design required approximately a third of the parts required in Difference Engine No. 1, while providing similar computing power.

Note how Babbage’s ideas were “engines.” These were machines, in the real sense. But this was the mid-1800s. Babbage was drawing up his schematics almost exclusively with ink and paper. There was very little “prototyping”. The designs had to be perfect.

Man without a pause

Babbage was an excitable guy when it came to any of the city’s “street nuisances.” In 1857 he penned an article in Mechanics Magazine that counted the source of 464 broken plate glass windows around London. At 55 occurrences, “Persons throwing stones” was the leading cause, and “Drunken men, women and boys” ranked at tenth with fourteen shatterings. He also stood before Parliament and argued against the popular street game of (essentially) hitting a piece of wood with a bat (called tip-cat) and rolling hoops.

Yet the street musicians during Babbage’s time weren’t going to just walk away. This was their livelihood. They sought to teach Babbage a lesson, playing outside his window incessantly.

“I have developed…an unenviable celebrity,” Babbage once wrote, “not by anything I have done, but simply by a determined resistance to the tyranny of the lowest mob, whose love, not of music, but of the most discordant noises, is so great that it insists upon enjoying it at all hours in every street.”

After a painful surgical operation, Babbage was certain that a brass band had conspired to keep him awake with their playing. Being bed-ridden with the band not far outside his window, Babbage said he was “compelled passively to submit to my tormentors.” Another time he sent his servant after the band and eventually called the constable. The law officer took down the musicians’ names and addresses. But the next day the department informed a frustrated Babbage that all nine band members had provided false information. Even on his deathbed in 1871, Babbage’s son writes that a guy kept encouraging kids to whack tin pails outside his window.

However it isn’t correct to cast Babbage’s plight as his alone or even something unique to London. He was simply one of its highest profile fighters. There were plenty of other voices at the time, including Charles Dickens. And the noise problem was growing across the industrializing world, in places like Germany, the Netherlands, New York and Chicago. In 1928, echoing Babbage, Henry Spooner of the London Polytechnic School of Engineering wrote that future generations would look back on an age in London that “tortured the thinkers” and “deprived countless invalids and workers of recuperative sleep.”

But at least at the legislative level, Babbage did get his way.

In 1864 lawmakers passed a new version of The Metropolitan Police act, known as Bass’s Act, which gave the police the power to tell street musician to scram or even arrest them. But there was only so much they could do. London continued to grow and so did the noise (and bigger problems for the cops). The Anti-Noise League formed in 1934, and doctors took up the cause, claiming the racket was a public health issue. As S.P. Signal points out in a history of noise pollution, only in the decades after World War II did cities really begin adopting standards to quiet things down.

Pride and pertinacious

In 2002 the London Museum of Science (LMS) finished building a version of Difference Engine No. 2. It weighed five tons, measured eleven feet and contained 8,000 parts. Construction took 17 years. And that was the thing. Though he managed to construct a portion of Difference Engine No. 1, Charles Babbage never saw his seminal inventions completed. In fact LMS’s version was the first time anyone had completed these machines, a full 153 years after Babbage died.

Doron Swade oversaw the reconstruction and points out that some historians attribute Babbage’s shortcoming to limits on Victorian part-smithing. On a reasonable budget, one simply couldn’t buy that many tools, gears and levers with that level of precision. But Swade points out that other machines, some of them pointless, were built at the time with the same level of complexity as the Difference Engine. The holdup went deeper than that. Compensation, funding from the British government and a discontinuity in negotiations were critical, Swade says, but the irascible genius’ personality probably had more to do with the failure than anything. He even had explosive meetings with Prime Minister Robert Peel.

“Babbage had lots of pride and hubris. He behaved as though being right entitled him to be rude. His quarrels with the British government and with chief engineer Joseph Clement might have doomed the project,” Swade notes.

“Only years later did we recognize the potential and power of the underlying machine architectures…We can now say with some confidence that had Babbage built this Difference Engine, it would have worked.”

![]()

This post was written by Caleb Garling. You can follow him on Twitter at @calebgarling.

Our next post is explores why men don’t volunteer as much as women. To get notified when we post → join our email list.