Every day since Thanksgiving, Ben Shafer-Rickles has been sitting on a New York City sidewalk from just after sunrise until well past sundown. If he leaves, his territory will be compromised, so all day he sits, beside a dense miniature forest, and barks at passersby.

“Hola! Quieres un arbol pequeno? Una gordita? Este cuesta veinticinco pesos.”

“Hey what’s up brother how you doing? How’s that tree doing?”

“Hi there are you looking to buy a tree?”

This winter, Ben is the man with the Christmas trees in Washington Heights — a neighborhood in Manhattan just north of Harlem. He is sharing an apartment for the month with eleven other tree sellers, but he calls a little 6-by-4-foot plywood shack he built on the sidewalk his “home.” He knows all of the local business owners, and he says they look out for him.

Ben describes himself as an extrovert who has trouble slowing down. One reason this job appeals to him is that it ties him to a street corner, day in, and day out, as one of the fastest-paced cities in the world rushes by. Sometimes, there’s nobody around and he’s alone with his thoughts. He says, “the hardest part of this job is doing nothing.”

When there is foot traffic, he channels his energy into courting customers.

“I’ll be here next year and you’ve got to tell me how it’s growing,” he tells a woman with a stroller, who is examining one of his few potted trees. “I bet it’ll be alright.”

“Yeah right!” she says, with a Spanish accent.

“You’ve got a kid I’m sure you can take care of a few things!” They chat. He coos over her three-month-old baby and she asks where he’s from.

“I’m from upstate and I live in California now,” he tells her. “But I love this neighborhood so much I come back here for a month every winter.”

“Yeah right,” she says again, sweetly.

Ben isn’t lying: he flew from sunny California for this job, selling trees on the sidewalks of New York City in the dead of winter. But why?

Duck Farmer Turned Tree-Seller

The short answer is: Money. Christmas trees in New York City are a peculiar market, and Ben’s making way more than the generic sidewalk salesman. His employer pays a salary plus commission after a certain quota for the month, which, Ben says, comes out to considerably more than a month of working a full time job for $20 an hour. For a lot of the flexibly employed people selling Christmas trees, it’s enough to live a couple months of the new year without having to work.

But he’s also in it for the adventure. Ben is currently transitioning between careers. He’s been working as a carpenter in the San Francisco Bay Area for the last year or so, but when he gets back he’s going to put some of his earnings from this gig towards training in massage therapy. Before carpentry, he says he was the biggest duck farmer in Vermont. An ecology major out of University of Vermont, he left agriculture when he realized he didn’t enjoy running a farm as a business.

“It’s not profitable to raise a hundred ducks, but if you raise a thousand it is,” Ben says. “I found myself making moral compromises and the welfare of my animals suffered.” He says that one night, a weasel broke into his barn and killed close to a hundred of his stock. When he saw the carnage, his immediate reaction disturbed him. “The first thing that came to my mind was ‘Oh shit I just lost a ton of money.’”

At around the time Ben was thinking of giving up the farm, one of his old travel buddies came into town. He says she knew exactly where he was “at” — “Which was that I didn’t know where I was at,” — and offered to hook him up with her gig tree-selling in Manhattan.

So he sold his farm and moved to a busy New York City sidewalk for a month while he planned his next move.

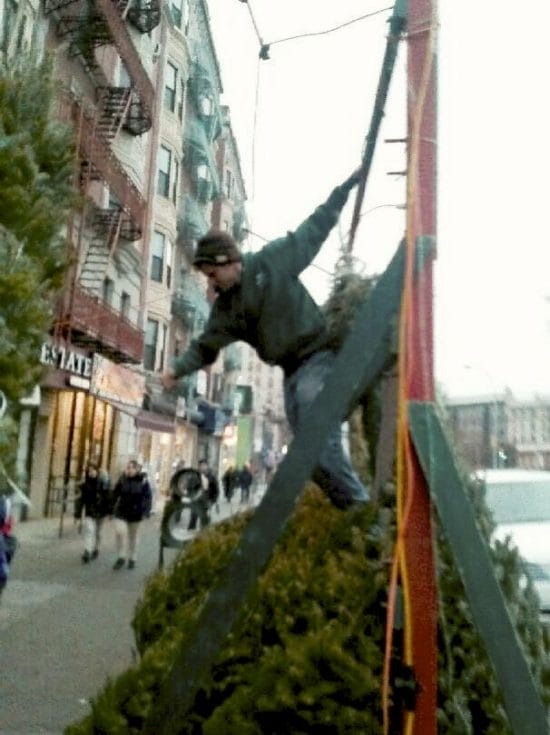

Ben Shafer-Rickles, slinging trees

Ben says he picked up the basics of the product pretty quickly: Fraser firs shed less, Balsams smell better, trees should be kept away from radiators and watered regularly. That’s about it. Trees are pretty different from ducks, but his farm background did help him understand exactly what he was selling in this concrete jungle.

“People have no connection to – I hate to use the word, but – nature. I see people who come by every day just to smell the trees,” Ben says. “Buying a tree here is their equivalent to going into the woods with a chainsaw and cutting one down with their hands.”

A lot of the other tree-sellers Ben has met are similar to him in a lot of ways. They’re young — Ben is 26, and his business partner, Joel Shupack, is 28. They’re able-bodied — not everybody can spend twelve hours every day for a month on a New York sidewalk in the dead of winter. And, for the most part, their lives are pretty flexible — not everybody can take off for a month for this kind of thing, either.

Joel, a folk musician and radio producer, also worked with Ben last year. They partnered up last fall when Joel rolled onto Ben’s duck farm in the middle of a cross-country bicycle concert tour. Joel says that now that he’s settled into a much stabler life in Portland, where he has a girlfriend and works at a bike shop, this year’s tree sale season has been a lot more taxing.

In any case, Ben says, the gig is worth it, at least in monetary terms. Though the boys bought their own plane tickets, once they were in the city their living expenses are negligible. The company rents them an apartment, customer tips cover food, and a lot of the neighboring shopkeepers pummel the salesmen with hospitality. “I had to start drinking coffee without sugar last year,” Ben laughs. “Because people were bringing me so many free cups I thought I was going to get diabetes.” What’s more the company pays for their lodging and their subway trips.

Where does all the money for salaries, apartments, travel come from? Well, for one, Ben and Joel sold 800 trees last year, at an average of $45 per tree. Their company – whose name they’ve asked we not print — has many other lots like Ben and Joel’s. They’re making hundreds of thousands of dollars in revenue in a month of sales, and they’re supposedly one of the smaller players in the New York City Christmas tree game. For another, the New York City Christmas tree game is completely unregulated – at least, so far as the city is concerned.

The Year the Mayor Ruined Christmas

New York City’s first Christmas tree lot was established on a sidewalk in 1851, according to a 19th Century New York Times article:

“Mark Carr, a jolly woodman, dwelling among the foot-hills of the Catskills, conceived the brilliant idea that New-York wanted Christmas trees, and he could make money by furnishing them. About two weeks before Christmas he drew two large shed-loads of these trees to the river with his oxen, and started with them to the Metropolis. Here he paid his silver dollar for the use of a strip of sidewalk on the corner of Greenwich and Vesey streets, and at once flung out his mountain novelties, which found buyers at good prices.”

Back then, a lot of things in New York City were sold on the sidewalk – Christmas trees, fish, meat, hotdogs, newspapers, milk. Sidewalk selling was enjoying an unregulated heyday, especially food vending. This had its upsides as well as its downsides. On the one hand it meant many immigrant entrepreneurs could sell knishes out of a cart with minimal start-up cost. On the other it meant they weren’t legally bound to wash their hands. It also meant that some of the processed ingredients they were using were pretty gnarly, because the factories the ingredients came out of weren’t held to any standards either.

At the turn of the century – as part of a movement inspired by Upton Sinclair’s novel The Jungle, about the meatpacking industry in Chicago – regulation started to develop, alongside a sense of consumer rights. As factories and brick and mortars started to have to conform to new laws, street vendors followed.

In the 1930s, New York City’s mayor, Fiorello La Guardia, tried to clear many street vendors off the streets entirely – including Christmas tree sellers. According to some historians, he was both trying to make the streets more auto-friendly, and force a large part of the working immigrant class out of the “lowly profession” of street vending, and into the official economy. Many of his efforts were successful, but not all of them. In 1938, he required a license to sell Christmas trees in New York City. These licenses were apparently difficult enough to get that many sellers didn’t get them, and everybody was upset – especially the people who couldn’t find a Christmas tree that year.

Mayor Fiorello La Guardia, who failed to regulate the street-side sale of Christmas trees

That year the New York City council, overriding La Guardia, voted for what the New York Times has called Ye Olde Coniferous Tree Exception:

“The city’s administrative code allows that ”storekeepers and peddlers may sell and display coniferous trees during the month of December” on a city sidewalk without a permit, as long as they have the permission of owners fronting the sidewalk and keep a corridor open for pedestrians. (The law originally cited Christmas trees, [not “coniferous trees,”] but the religious reference was removed in 1984.)”

Today, although street vending is common in New York, regulation is king. Street vendors of food need licenses to operate legally, which can take years to acquire. Although the trade of knock-off handbags and jewelry is still bustling, it’s been driven off the sidewalk, behind close doors. Sidewalk artists have to tailor their booths and displays to meet city guidelines, and often get fined for things like a stand being too large.

Christmas trees, however, have retained their exceptional status. So far as the city is concerned, you don’t need any kind of permit or license to sell that Christmas tree on the street. And your lot can look as kooky, big, or cluttered as you want.

This kind of makes sense: The city’s appetite for Christmas trees is as voracious as ever. There still isn’t enough rentable outdoor space to house all the trees the city consumes, and it’s illegal in New York to sell them indoors – they’re too much of a fire hazard. Plus, unlike with knock-off handbags which threaten the fashion industry, or street food which competes with local restaurants, there aren’t more-powerful, established and regulated sellers for these sidewalk sellers to compete with. Christmas trees aren’t as bold visual statements as some art displays, and customers only want the trees as ornaments, only for a few weeks out of the year, so as long as they don’t spontaneously combust, “quality control” isn’t really an issue. Consumers appreciate the convenience of sidewalk tree selling, and it doesn’t seem that anybody has reason to push for regulation, at least not anybody powerful.

Permits, licensing, coded infrastructure, and sales tax, all cut into a business’ operating cost. Not having to deal with them means a larger percentage of a tree seller’s revenue is pure profit. This is where “all that money” for Ben and Joel’s salary, housing, and transit comes from.

The Dark Side of Unregulated Retail

Ben and Joel’s “home” for the month

But to say that the Christmas tree market in New York is entirely unregulated is somewhat inaccurate. The Christmas tree market might not be regulated by the city government, but there are plenty of rules a tree seller has to observe, and plenty of butts he has to kiss. For those who don’t, they say, there are major consequences.

Sidewalk tree sellers do have to pay a kind of rent. Getting store owner’s “permission” to set up on there sidewalk usually entails giving them money, because if you don’t another tree seller will. Ben says he’s paid off all of his neighbors – a barber, a spa, a 99 cent store, an apartment building, and a real estate office – in order to set up where he has.

Another limitation a sidewalk tree seller has to conform to is that he can’t set up too close to another sidewalk tree seller, because there’s a chance the established seller’s employer will send some goons to break the intruding seller’s kneecaps, take all his cash, and mess up his trees. That’s what Ben and Joel seem to think, at least.

“It’s a very secretive business,” Joel says. “There’s a lot of money in it, and a lot of cash floating around at any given time. Nobody wants any scrutiny, so there’s a lot of mystery around things.”

Many tree sellers don’t know much about the people they’re working for. They pick up the trees at a drop-off location, are told an average price at which to sell them. Somebody comes and collects their earnings at the end of the day. Though New York City tree sellers are mostly adventurous young travelers, they don’t comprise a broader community – Ben and Joel rarely spend time with other tree sellers outside of the apartment they share with coworkers. Tree selling companies seem to only hire out-of-state employees, and Ben and Joel say this is because native New Yorkers are more likely to have the local connections necessary to sell the company out to competitors, gangsters, or petty thieves looking to make a quick score.

“I’m pretty sure that my company probably has some people looking out for them,” Ben says, and asks us not to name his employers in this article. He says they’ve been “great,” and he “wouldn’t have come back if it weren’t for them,” as he thinks they treat their employees much better than many other Christmas tree companies he’s encountered.

Leaving the company anonymous might be a very wise move. There’s at least one suspected case of a Christmas tree company punishing its employees for merely speaking with the press. Kevin “the Myth” Hammer, the industry kingpin, denied two Quebecois employees payment in 2007 — allegedly as punishment for stealing from him, which the young men denied doing. This all happened shortly after they were quoted talking about their gig, and their shadowy employer, in an article in the New York Sun. The journalist hadn’t printed their names, but had described the interview as occurring over a meal of “chicken fingers and cognac,” which the Quebeccers said was referenced in their termination:

“After Hammer told us we weren’t getting paid, I got a text message from my supervisor that said: ‘Apparently you steal and talk too much. Chicken fingers and cognac are not a good combination.’”

Because Christmas tree retail is less regulated, labor practices seem to be, too. Ben and Joel are each working 12 hours a day for a month straight, with only a 6 by 4 plywood shed for shelter. It has a heater, but it still was none too cozy last year. “There was one night I just sat in the booth in all of my warm clothing,” Joel says. “And I couldn’t get warm enough. That’s all I did the whole night. I didn’t do any actual work — I literally couldn’t leave the shack.”

Ben and Joel have also asked us not to name their closest competitor, who opened a stand just a few blocks away from theirs this year – they say in violation of an inter-company agreement. Even though the other stand’s presence appears to have cut into sales, Ben and Joel say the competing company is more powerful than their own, and they’re are afraid to cross it. Joel says he’ll sometimes talk to other tree sellers he sees on the street about the business, and when he mentions this particular company’s owner, a chill often falls. “The fear I see on people’s faces when I mention him,” Joel says. “It’s unlike anything I’ve ever seen.”

Ben swears he’s not packing heat beneath the counter of his shed, “But I won’t say nobody is.” He says Joel, who works the night shift, isn’t armed either, though he’d have more incentive to be. Ben’s shift is from 8 AM to 8 PM, after which he often grabs a slice and hits the town, will sometimes catch a play on Broadway.

He rarely worries about his safety because the neighbors are looking out for him. A few weeks ago, somebody stole Ben’s phone out of the shed. “All the storefront owners came out and were infuriated that someone had taken something from me,” Ben says. Some of them spent hours trying to help him track it down.

Even in the city that never sleeps, a lot of the stores on his block are closed during Joel’s shift. His job is to sit on that street corner from 8 PM to 8 AM, rain or shine. “The things Joel sees,” Ben laughs. “I don’t know what he sees. I don’t want to know what Joel sees.”

3 AM Christmas-Tree Cowboy

The view from Joel’s window

One of Joel’s recent late-night customers pulled a bill out of his wallet that was folded up into the size and shape of “a wedge of Trident gum.”

“He unfolded this bill,” Joel says, “and took out another bill and emptied the powdery white contents of the first bill into it. Then he handed the first bill to me.”

The man with the powder wasn’t buying a tree, he was buying one of the 130 little wooden reindeer Joel has constructed out of Christmas tree scraps. The night shift is typically slower than the day shift, and he says it’s common for sellers to whittle to pass the time, and sell their crafts alongside the trees. He say that even with tree sales being down from last year because of their new competition up the road, he’s making more money this year because he’s sold so many of these reindeer. He also says we might be surprised by the amount of business he gets, “It’s New York City, I see people walking around with their kids at 3 AM — some people here just have weird schedules.”

This is Joel’s second year working the night shift, and he’s pretty relaxed about it. He was jumpier last year, before knew the neighborhood. He now understands he’s not a target. The company collects Ben’s Christmas tree earnings at the end of each day shift, so Joel rarely has much cash in the shed. He says that most of his job is to just watch over the trees to discourage inventory theft, as the neighborhood’s night life goes by.

Joel’s reindeer

“I see drug-addicted kind of desperate-acting people,” Joel says. “And hustlers trying to get money off people in different ways. There’s a guy who says, ‘Oh I had a bus ticket to Philadelphia to see my family and I just lost it and I need $20.’ I see him every night: why isn’t he in Philadelphia yet?”

“I see fights, some of them really nasty. I’ve called the cops. I see a woman who comes up the block at midnight with an empty shopping cart and back down at 4 in the morning with an unbelievable number of cans. I see people going to work in the morning.”

Sometimes he’ll leave the shed to go to the bathroom, or buy food, and come back to see one of his trees “walking down the street.” The last time it happened: “It was 2 AM and I was kind of delirious and I thought, ‘Gee, I wonder where he got that tree,’” Joel says. “Then I thought, ‘Wait a minute I know where he got that tree!’”

He confronted the guy carrying the tree politely. The guy said, “Oh, I thought they were free,” and handed it back. Joel returned it to his lot and sat back down and waited out the rest of the night.

Ben relieves Joel at 8 AM every morning, and Joel goes out to “breakfast” and wanders around the city a bit. Sometimes he goes to the park and sit in the sun. Last week he went to the Museum of Natural History. “There’s a particular energy to a morning after staying up all night,” he muses. “You’re physically tired but there’s a euphoria because of the sunlight. Everything is so bright and beautiful.” Finally, he heads back to the apartment, and sleeps on whatever soft surface is available for as long as possible before his next shift.

Away from Home for the Holidays

The shed at night

In just a few days, early morning of December 25th, Ben and Joel will close up shop. They expect to have 15-20 trees leftover, which they’re told the city collects for mulch. When Joel gets back to Oregon in a few days, he’s going to get his sleep schedule back on track and go on vacation with his girlfriend. Ben’s visiting his family upstate, and then going on a road trip with a lover before returning to the San Francisco Bay Area.

Joel says one of the most common questions he and Ben get from customers is what they’re doing spending the Christmas away from their families. The thing about this is — Ben and Joel are both Jewish. Ben’s family was never particularly religious, and Joel whittled himself a menorah of a Christmas tree stump this year. As Ben put it, “We’re a couple of Jewish dudes selling Christmas trees on the street.”

Joel says it’s pretty common for non-Christians to sell Christmas trees, because the job usually involves being away from home for Christmas. “I think it’s kind of great,” Joel says. “If someone has to sell the trees, it should be someone who doesn’t have to miss out on the holiday.”

Even though they don’t celebrate Christmas, they’re extremely respectful of the emotional significance of what they’re selling. “It’s a weird job,” Ben says. “You’re dealing with much more than just money and trees.”

Sometimes a customer will try to buy a tree with a bag of change. When that happens, even if he’s been worn-down by a grueling daily grind, Ben will often just give the tree away. “This is a heavily Catholic neighborhood. For some people its super important that they do get a tree. I’m not trying to take their money.”

It seems that this kindness ultimately pays off: Last year Ben and Joel sold more trees than anybody ever had at their location. They’re doing pretty well this year, too, but neither of them knows whether they’ll be up to do it all over a third time next year.

If they decide not to give another month of their lives to the Christmas tree game, they’ll gift their jobs away — to whomever they think could benefit from a boatload of “quick” cash, and hundreds of hours “doing nothing” on a New York City sidewalk.

Our next post is about how the KKK was a giant, racist pyramid scheme in the 1920s. To get notified when we post it → join our email list.

This post was originally published in December, 2014, and was written by Rosie Cima. You can follow her on Twitter here.