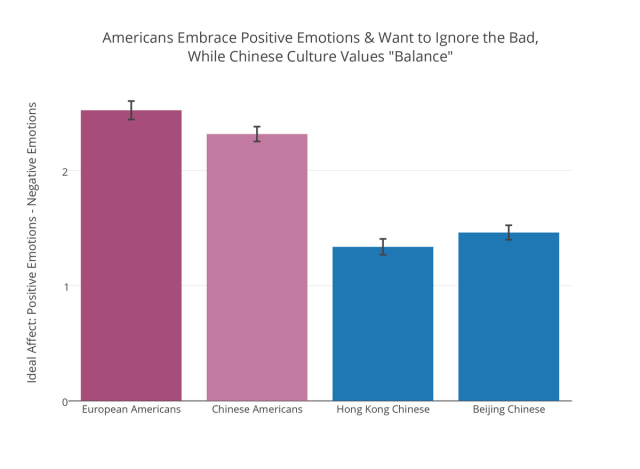

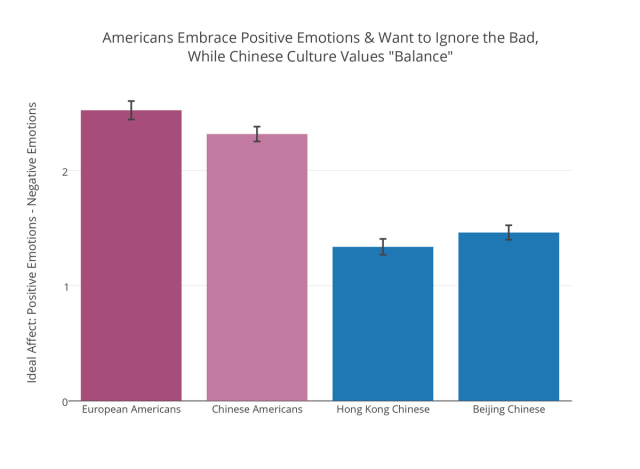

Rosie Cima, Priceonomics; data Sims et. al.

Everybody wants to feel as good as possible, and avoid negative feelings as much as possible — right? Wrong.

According to studies in cross-cultural psychology, the kind of emotional life people want varies a lot from culture to culture. In the West, we tend to assume that everybody wants what we do: to optimize for our own happiness, enthusiasm, and excitement. People from east Asian cultures tend to value calm, relaxed, and peaceful experiences over “exciting” ones. Psychologists say this difference is expressed in social behavior. One example is that, in a study, Asian participants were more likely to favor calm classical music over more exciting classical music that was louder or faster-tempo. Another example is that the drugs most commonly abused in the United States are stimulants, like cocaine and amphetamine. In China, they’re opiates like heroin.

The differences go deeper than that. Stanford University psychologists Tamara Sims and Jeanne Tsai recently conducted a series of studies, in collaboration with researchers at the Chinese University of Hong Kong. According to their findings, compared to ethnically-European Americans, people from Chinese cultures care less about having positive feelings, and about not having negative feelings, at all. As a consequence, Chinese people are more likely to experience “mixed emotions” — negative feelings, alongside positive ones.

“It is impossible to be happy forever,” a Chinese student in Hong Kong is quoted in the paper. “I think life is sometimes up and down. I want to have both balanced sadness and happiness.”

Palm Pilot Happiness Program

Happy people; photo: Marc Kjerland

Earlier research had already shown that, in addition to the ideal emotional life varying from culture to culture, the emotions people actually experience vary as well.

In the United States, people who report generally experiencing high levels of positive emotions tend to report experiencing low levels of negative emotions. Among East Asian samples, negative and positive emotions are “typically unrelated or even positively correlated” (i.e. the more “good” feelings subjects feel, the more “bad” feelings they also feel). In studies of momentary — not general — emotions, negative and positive emotions were negatively correlated across the board, but much more strongly for North American, compared to East Asian, samples.

“[Few studies] have examined how people’s ideal affect shapes their actual affective experiences,” they write. “Does wanting to experience positive and negative affect make individuals more likely to actually experience a mix of positive and negative affect?”

To answer this question, they gathered a sample of people from several different Western and Eastern cultures: ethnically European Americans, Chinese Americans, Hong Kong Chinese people, and Beijing Chinese people. Participants were asked to carry a Palm Pilot with them for 7 days. The Palm Pilot prompted them, five to six times a day, to report on their actual feelings at the moment and their desired feelings. They answered questions like: “On a 5-point scale, how happy (or calm, enthusiastic, angry, anxious, bored, sad) are you? How happy would you ideally feel?”

By averaging the scores for ideal positive emotions (calm, enthusiastic, happy), and doing the same for negative emotions (angry, anxious, bored, sad), the researchers were able to calculate a difference score for positive and negative affect. The larger the difference, the more a subject wanted to maximize their positive emotions and minimize their negative emotions.

Rosie Cima, Priceonomics; data Sims et. al.

They found that ethnically European Americans tended to want to maximize positive and minimize negative emotions more than Chinese Americans, who in turn wanted to maximize positive over negative emotions more than Chinese people in Hong Kong or Beijing. They also found a strong correlation between these scores and actually experiencing “mixed” emotions (positive and negative emotions at the same time):

“We […] found that the greater the difference between ideal positive and negative affect (i.e., the more participants wanted to feel positive relative to negative affect), the lower the likelihood of experiencing mixed emotions.”

Yet another study reinforced this finding. In it, subjects were made to watch television clips. Researchers found that instructing subjects to focus their attention differently, correlated to differences in their emotional experience. People who had done an exercise prior viewing through which they were instructed to, “focus only on the good feelings,” and “try to ignore any bad feelings,” were less likely to experience mixed emotions viewing the clips.

Happy Individuals Versus Happy Community

Middle school classroom in China (photo: Rex Pe)

Chinese culture seems to value mixed emotions more than American culture does. But why? The researchers attempt to answer that question: They have evidence that it has to do with cultural attitudes towards independence and interdependence.

Prior to the palm pilot experiments, participants were also surveyed on how much they valued traits relating to independence, (including: “influential (having an impact on people and events),” “independent (selfreliant, self-sufficient),” “choosing own goals (selecting own purpose),”) and interdependence, (including: “politeness (courtesy, good manners),” “reciprocation of favors (avoidance of indebtedness),” “respect for tradition (preservation of time-honored customs).”

“Above and beyond the effect of culture,” the researchers write, “the more people valued independence over interdependence, the more they wanted to feel positive over negative affect. […] Cultural differences in how much people want to maximize the positive and minimize the negative are due at least in part to how much they value independence versus interdependence.”

Cultural studies have long categorized America as having an “individualistic culture” — promoting individual autonomy and interdependence. China, on the other hand, is understood to have a “collectivist culture” — promoting instead the interdependence of individuals and the notion of social harmony.

The researchers hypothesize that, when an individual’s value system puts more emphasis on the individual, as opposed to the greater good, their own happiness — and freedom from suffering — becomes much more important. “Because being a good independent self means differentiating oneself from others in positive ways,” they theorize, “individuals from these contexts want to stand out in a positive light, which also means wanting to feel good and not feel bad.”

In a collectivist society, on the other hand, feeling too good could be undesirable, if it poses a threat to harmony. And negative emotions might be seen as more advantageous in more collectivist cultures, for a variety of reasons.

“I’m writing a song all about you / A true song as real as my tears / But you’ve no need to fear it / Cause no one will hear it / Cause sad songs and waltzes aren’t selling this year.” – Willie Nelson

The first time an American teenager gets dumped, the stereotype is that they finally “get” country music, in a way they had never before. The unprecedented experience of loss lets them connect to humanity at large, and is a “silver lining” on a mostly unpleasant experience.

The researchers hypothesize that if someone places a higher value on interdependence, they’ll also place a higher-premium on this kind of suffering-derived understanding. “[W]hen individuals feel negative emotion,” they write in the paper, “they may attune more to others, which again would facilitate interpersonal harmony and help individuals fit in with other members of the group.”

This post was written by Rosie Cima; you can follow her on Twitter here. To get occasional notifications when we write blog posts, please sign up for our email list