An image from the film “Snowden” depicting a polygraph test

You’ve been arrested for a brutal murder you didn’t commit. The evidence is circumstantial, but the police are convinced you’re the killer. The prosecutor offers you a deal. They’ll drop the charges, but only if you take a polygraph test to prove your innocence.

What would you do?

Unfortunately this is no hypothetical, but rather a scene from a real life nightmare.

In 1978, Fred Ery was working in his general store in Perrysberg, Ohio, when a masked assailant burst in and shot him. Before he died on the operating table, he was able to tell his wife the name of his killer, and even gave detectives his address. It seemed like an open-and-shut case, and police soon had Floyd “Buzz” Fay’s house surrounded.

Fay later failed a polygraph test not once but twice. With the results admitted into evidence during his trial, he spent the next two and a half years in prison before he was exonerated when the mother of the real killer came forward. During this time, Fay became a vocal campaigner against the polygraph, even appearing on NBC’s “Today” show after his release to call for polygraph tests to be banned from criminal trials.

Nearly 40 years later, the polygraph still commands something of a towering cultural presence in modern day life. From Hollywood movies to infamous criminal cases to daytime television, it’s used as a definitive arbiter by both the justice system and entertainers.

But can a machine really detect lies?

How the Polygraph Captured Our Imaginations

The polygraph is based on the theory that the act of lying elicits an emotional response, and that measuring this response can distinguish lies from the truth. This idea can be traced all the way back to the Inquisition, when suspects were sometimes made to swallow bread and cheese. If the food stuck to their palette, the lack of saliva was seen as an indication of a guilt.

In the early 19th century, American psychologist William Moulton Marston—building on the work of others before him—carried out research that claimed to show a correlation between systolic blood pressure and lying. Though this research attracted skepticism, Berkeley police officer John Larson used it to create the first polygraph machine in 1921, which measured both blood pressure and breathing rates.

Larson’s protege Leonarde Keeler later refined this ‘cardio-pneumo psychogram’, making it portable and adding a way to measure electrical activity in the skin. In doing so, he created the prototype for the modern-day polygraph, which today measures a range of physical changes that examiners claim can be used to detect deception.

The creators of the polygraph were instrumental in its early adoption. Using a combination of clever publicity stunts and support from police and justice officials, they ensured it became known for solving crimes that police alone couldn’t.

The polygraph’s first major test came just months after its invention, when the San Francisco Call and Post arranged for John Larson to test murder suspect William Hightower. Larson was convinced that Hightower was lying, and the paper’s resulting headline boldly declared: “Science Indicates Hightower’s Guilt.”

It was a remarkable publicity coup for Larson’s nascent machine, helped by Berkeley police chief August Vollmer, who touted the machine as a “lie detector” to the waiting press. Vollmer was a leading figure in police reform in the 1920s and one of the polygraph’s earliest backers. He saw the machine as a way to further scientific interrogation and end the so-called “third degree”: the police practice of obtaining information by beating suspects up.

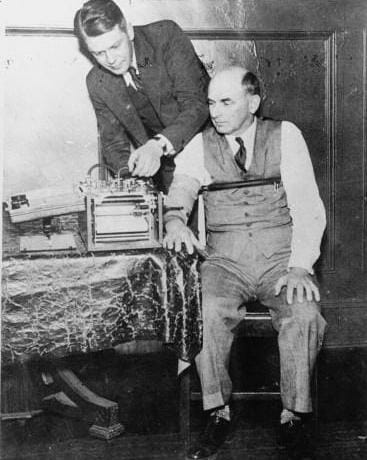

Both John Larson and Leonarde Keeler were called upon numerous times to test suspects in criminal cases, and the polygraph became a significant factor in a number of trials. Keeler was known to be a master of eliciting confessions purely by hanging the threat of the polygraph over suspects. He even appeared as himself in the 1948 film “Call Northside 777”.

Leonarde Keeler testing a witness at a trial. Photo via Wikipedia

Meanwhile the self-styled “father of the polygraph,” William Moulton Marston, lobbied hard for its use in the courtroom. He even wrote a book called Lie Detector Test. Ever the self-promoter, Marston—who also created Wonder Woman—pushed the polygraph into its first forays as an object of cultural fascination. In 1938, he appeared in Gillette advertisements claiming that the polygraph showed the company’s razors were better than the competition.

In the world of criminal justice, the polygraph promised to do something previously considered impossible, to break a habit as old as man. However, despite the enthusiasm of police and prosecutors, it was immediately hampered by a 1923 U.S. Supreme Court ruling that ruled out polygraph evidence until it was “sufficiently established to have gained general acceptance” by the scientific community.

Courts of appeals have generally upheld this principle in the years since, which has made the use of polygraphs in formal legal contexts a rarity. But there have been exceptions, like in the case of Floyd “Buzz” Fay, where individual judges allowed polygraph evidence. In rare cases, both the defence and prosecution agree on the admission of polygraph evidence.

A 1998 Supreme Court ruling further upheld the consensus on polygraph evidence, stating that “A fundamental premise of our criminal justice system is that ‘the jury is the lie detector.’”

Nearly one hundred years since its invention, the polygraph has never been able to achieve the scientific consensus the courts required. Instead it lurks in the background of the justice system, used by police to obtain confessions, or by suspects desperate to prove their innocence. It’s widespread only where the Supreme Court ruling does not apply: daytime television and intelligence agencies like the CIA.

The reason for this is simple. The polygraph can be an effective interrogation tool. But when it comes to detecting lies, it simply doesn’t work.

The Science Doesn’t Lie

The question of whether polygraphs can detect lies is an open-and-shut case.

There have been relatively few scientific studies on the polygraph, but a National Research Council study from 2002 is the most comprehensive to date. Asked by the U.S. Department of Energy to investigate the polygraph, the NRC considered all previously published scientific studies and relevant data.

The NRC ultimately concluded that for people “…untrained in countermeasures, specific-incident polygraph tests can discriminate lying from truth telling at rates well above chance, though well below perfection.”

But the study also concluded that “…truthful members of socially stigmatized groups and truthful examinees who are believed to be guilty or believed to have a high likelihood of being guilty may show emotional and physiological responses in polygraph test situations that mimic the responses that are expected of deceptive individuals.”

To put it bluntly, the polygraph can be an effective interrogation tool in the hands of the right examiner, but there’s a real danger of the test producing ‘false positives’ (misclassifying innocent people). And minorities facing biased assumptions of their guilt are especially likely to be nervous during a polygraph and fail the test.

The NRC further found that when it came to screening intelligence employees, the polygraph’s “accuracy in distinguishing actual or potential security violators from innocent test takers is insufficient to justify reliance on its use in employee security screening in federal agencies.”

Intelligence agencies therefore run the risk of obtaining ‘false negatives’ (failing to detect enemy spies), making the polygraph a potential danger to the state as officials can be lulled into a false sense of security.

Photo by Gabriel Rodriguez

Despite this, the polygraph is widely used by government agencies in the United States for screening purposes, while most federal law enforcement agencies still use it as an interrogation tool. In some states, the polygraph is even extending its reach, and is now used to monitor compliance on Sex Offender Treatment Programs.

Today there’s an active community campaigning against the polygraph, often under the banner of the late U.S. Senator Sam Ervin, who famously described it as smacking of “20th century witchcraft.” This small group of campaigners includes those wronged by the tests, such as Floyd “Buzz” Fay, former police and FBI agents who warn of the dangers of continued polygraph testing, and even scientists concerned about being screened by the U.S. government.

George W. Maschke, a former Army Intelligence Officer and a founder of AntiPolygraph.org, says he is one of the polygraph’s unseen victims. After years of public service, he applied to work for the FBI, only to be branded a liar by a polygraph examiner and permanently disqualified from employment. According to Maschke, use of the polygraph should be ended because polygraphy “…is a pseudoscience that relies on deception by the polygraph operator and public ignorance of the trickery on which the procedure depends.”

Proponents of the polygraph—led chiefly by the American Polygraph Association—claim that the test has a proven track record amongst government and police officials, hence why it’s still in use to this day.

Despite such claims, even the APA’s own arguments acknowledge that the polygraph is not a lie detector test. “Though it is colloquially referred to as a ‘lie detector’ test as a term of convenience,” the APA writes, “science and scientific reason do not suppose that the polygraph actually measures lies per se.”

This reflects the fact that modern day examiners—perhaps in light of the scientific consensus—concentrate on what they see as the strengths of the polygraph, and steer clear of the sensational claims made by Keeler and Marston.

These examiners are so important to the polygraph’s success precisely because it’s not the machine detecting lies, but rather the person behind it—at least according to former examiner Doug Williams.

Williams was imprisoned for helping people “game” the polygraph, and he has described the machine as an “insidious Orwellian instrument of torture.”

“There is no such thing as ‘lying reaction,'” he has said in interviews. “What the polygraph operators are claiming is that every time your breathing becomes erratic, your blood pressure increases, and the sweat activity on your hands increases, that this reaction indicates deception. The problem is that the scientific evidence all proves that while this reaction may be induced by the stress of lying, about fifty percent of the time, the problem lies in the fact that simple nervousness, embarrassment, [or] even the tone of the examiner’s voice can elicit a reaction that would brand you as a liar.”

There’s also likely a wide gulf between examiners’ perception of their ability to detect lies and the reality. There have been a number of studies on “human lie detecting”, and the scientific consensus is that people who believe they can detect lies, such as police officers, are actually little better at doing so than members of the public.

Pinocchio’s nose remains the only true lie detector test. Screenshot from Disney’s “Pinocchio.”

Of course the polygraph’s reputation hasn’t been helped by the ones that got away, and infamous cases from enemy spies to mass-murderers have littered the machine’s record since its invention.

Perhaps most notoriously, when Gary Leon Ridgway was suspected of being the Green River Killer in the 1980s, he joined hundreds of other suspects who were questioned and asked to provide DNA samples. DNA science was still developing at the time and did not connect him to the case. When Ridgway agreed to take a polygraph, he passed easily, removing himself from suspicion.

It wasn’t until 2001 that those DNA samples could be conclusively linked to the victims, and in 2003, Ridgway finally stood up in court and confessed to the murders of 48 women who he had dumped in Seattle’s Green River. Of Ridgway’s polygraph test, his attorney Eric Lindell told the BBC, “He said he didn’t do anything special to pass it. He just relaxed. But then he is a unique individual.”

Ridgway exemplified what’s known as the polygraph’s “psychopath problem”. This is the theory that a psychopath’s lack of anxiety and emotional response would allow a percentage of the population to “beat” the test.

But campaigners don’t believe the polygraph has a problem with a segment of the population. They instead argue that anyone can beat the polygraph with a simple set of techniques known as countermeasures. The most famous of these is the tack-in-the-shoe method, whereby a suspect presses down on the tack to produce increased physiological responses at the right moment. Another is to practice a consistent breathing rate between 15 and 30 breaths per minute.

In reference to such techniques, former FBI crime laboratory official Drew C. Richardson told a Senate panel in 1997 that “… both my own experience and published scientific research has proven that anyone can be taught to beat this type of polygraph exam in a few minutes.”

Due to these abundant shortcomings, polygraphs are not used by police or in courtrooms in most of the world. Polygraphs are an example of American exceptionalism.

The Polygraph Bluff

So if the science is clear, why is the polygraph still so widely used today across government agencies and police departments in the United States, and in a smattering of other countries such as Israel and Canada?

One reason is that proponents of the polygraph have had nearly one hundred years to lobby for its use, and police and justice departments are loath to give up a powerful interrogation tool, regardless of the scientific consensus against it. We also know that institutional culture is incredibly hard to change once it’s in place.

Many American detectives to this day cling to interrogation techniques designed to produce confessions, despite a lack of scientific evidence supporting them. Consider the Reid Technique, which was developed in the 1940s (by a polygraph examiner) and aims to make suspects more comfortable with confessing a crime. To do this, investigators assume an understanding demeanor while assuring the suspect there is no doubt of their guilt, before giving them morally acceptable justifications for the crime.

Even though the technique has been found to produce false confessions—a landmark 1955 confession extracted by Reid himself was proved to be a false 33 years later—and inspired the Supreme Court to require Miranda rights, American police forces continue to employ the Reid Technique.

In the world of entertainment, the polygraph’s appeal is equally obvious, offering the prospect of drama and an instant decision. However, while a criminal suspect is at least afforded a degree of checks and balances, for the TV show participant, no such shield exists.

In the UK, “The Jeremy Kyle Show” uses a polygraph examiner to assert guilt in the cases of cheating partners or thefts within the family home. Neither Kyle nor those taking part acknowledge the show’s disclaimer that “The lie detector is designed to indicate whether someone is being deceptive. Practitioners claim its results have a high level of accuracy, although this is disputed.”

Ironically, daytime TV’s love affair with the polygraph is likely what keeps the machine and its advocates in business. A pernicious effect of the polygraph’s use in pop culture is that it bolsters the machine’s reputation. The more its reputation is reinforced by TV hosts’ credulous use of polygraphs, the more successful it becomes as an interrogation tool when used by the police or government agencies.

This may help explain why the American government continues to use polygraph tests. Both the CIA and NSA routinely screen prospective and existing employees, and the NSA even released a PR video on its use. Notably, American law has banned private employers from using mandatory polygraph tests since 1988.

A government training facility that includes training in polygraph tests. Photo by the Pennsylvania National Guard

Despite these agencies’ enthusiasm for the polygraph, history is filled with examples of enemy spies who passed polygraph tests undetected.

Amongst the most infamous is the case of Aldrich Hazen Ames, who spent 31 years as a CIA counterintelligence officer and analyst, despite being a mole for the KGB. He remains in prison after being convicted of espionage in 1994, and a letter he wrote from prison to the Federation of American Scientists sheds some light on why intelligence agencies use the polygraph:

Its most obvious use is as a coercive aid to interrogators, lying somewhere on the scale between the rubber truncheon and the diploma on the wall behind the interrogator’s desk. It depends upon the overall coerciveness of the setting — you’ll be fired, you won’t get the job, you’ll be prosecuted, you’ll go to prison — and the credulous fear the device inspires… Because interrogations are intended to coerce confessions of one sort or another, interrogators feel themselves entirely justified in using their coercive means as flexibly as possible to extract them. Consistency regarding the particular technique is not important; inducing anxiety and fear is the point.

We’re left then with a scenario that must often be little more than a charade, with both examiner and examinee aware of the polygraph’s shortcomings.

A 1983 report by the US Congressional Office of Technology Assessment concluded, “It appears that NSA (and possibly CIA) use the polygraph not to determine deception or truthfulness per se, but as a technique of interrogation to encourage admissions.”

This gets to the root of why such a derided technology is still widely used, and the answer leads all the way back to Leonarde Keeler’s famous ability to bluff suspects into a confession without even turning the machine on.

The polygraph survives on belief. Examiners’ belief that they can discover the guilty, and examinees’ belief that they can be discovered.

When people believe it works, the polygraph can discover deception at rates slightly greater than chance. But it comes at the cost of certifying many false results, especially when examiners test someone who understands the con and employs countermeasures.

The human cost in all of this is obvious. From Floyd “Buzz” Fay to Gary Ridgway to Aldrich Ames, the history of the polygraph is a history of failure, and the fact that the polygraph is still in use is in no way indicative of its abilities.

There’s a rich history of inventions that seemed too good to be true… and were. British businessman James McCormick was able to sell £50m of ‘bomb detectors’ (re-purposed golf ball finders) around the world before being jailed in in 2013. These useless wands turned up in the fight against poachers in Africa, Mexico’s drug wars, and the burgeoning insurgency in Southern Thailand. Until this year, they were still used in Iraq, a country that really can’t afford to use a fake bomb detector.

From miracle diets to get rich quick schemes, people will always be susceptible to ideas that seem too good to be true, and we should never discount our desire to believe. Especially when we’re being offered a simple solution to a complex problem.

The polygraph offers an enticing solution to an innately human problem, but at its heart, it’s a big lie. A pretence that a machine can uncover your hidden secrets, a clever tool of interrogation masquerading as scientific instrument.

Our next article investigates whether it’s true that most people order the second cheapest wine on the menu. To get notified when we post it → join our email list.

![]()

Note: If you’re a company that wants to work with Priceonomics to turn your data into great stories, learn more about the Priceonomics Data Studio.