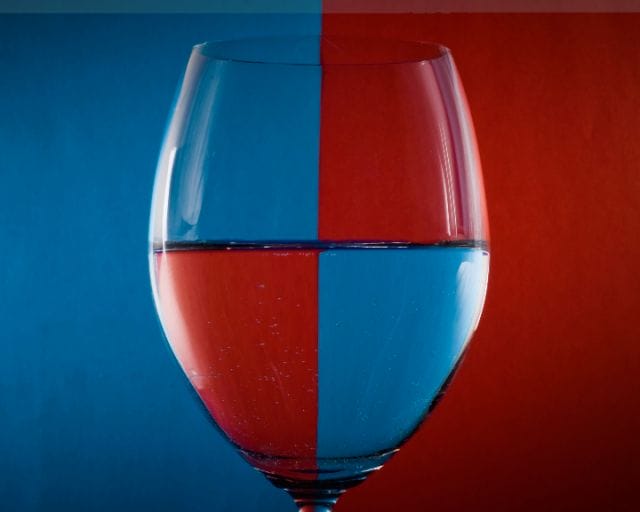

Photo credit: Pen Waggener

If you head to Ray’s and Stark Bar in Los Angeles for a $25 house made pasta or a $30 steak, you will not just be poured a glass of tap water. At Ray’s and Stark Bar, servers hand patrons a 46-page “water menu” that contains descriptions of 20 different bottled waters along with tasting notes for each, prices from $8 to $20 per bottle, and quotes from Wallace Stevens and Leonardo da Vinci. Confused? General Manager and “water sommelier” Martin Riese can help answer the inevitable question, “Isn’t it all just water?”

“Yes and no. They’re definitely all water. So they all come from the same ‘source’ because [they were] all rainwater at some point,” Riese told an incredulous Conan O’Brien, who invited him on to late night television to explain why the world needs water sommeliers. But when they are “raining down on different salts and layers of the ground — like wine kind of — [they] take minerals with them so they taste differently. You can say this water comes from Spain, it tastes more salty and bitter than a water that comes from the Finnish Islands.”

Riese, who hails from Germany, points to his accreditation from the German Mineral Water Trade Association and his own enthusiasm for the tastes of different waters as job qualifications. The press dubbed him a water sommelier, and he embraced the title as a “water expert” sounds more like a municipal worker testing a reservoir’s pH level than someone advising diners in a chic L.A. restaurant.

Riese’s efforts to turn water into wine have not been greeted warmly. “When I started the program,” he told Vice, “you wouldn’t believe the amount of hate emails I received from unreasonably pissed off people.”

The problem with mocking Riese, however, is that his choice of career seems rather astute. In 2012, Americans drank 9.67 billion gallons of bottled water. Can it really be that stupid to be a water sommelier in a country where people drink more bottled water than beer?

Too Good for Tap

In the United States, bottled water is a $12 billion industry based on people paying from 240 to 10,000 times as much for a product that flows out of their taps for less than half a penny per gallon.

Environmentalists absolutely hate this parallel system. Many people in countries that lack a dependable municipal supply of clean water do rely on bottled water. In the United States, however, where safe drinking water flows out of taps and public water fountains, the bottled water industry is almost pure waste. Each liter of bottled water requires roughly three liters of water to produce. During a recent vote that banned the sale of bottled water on San Francisco property, Board of Supervisors President David Chiu held a bottle of water filled a quarter of the way up with oil to demonstrate the amount of oil used to manufacture and transport each bottle.

It may make sense to buy Perrier or San Pellegrino if you like sparkling water. And sure, people may prefer to buy a bottle of water during an excursion rather than schlep around a water bottle. But why do so many Americans buy bottled water every grocery trip when it’s already available at home for free?

One reason is the perception that bottled water is cleaner and healthier than the stuff we get for free. The images printed on bottles of water of remote springs and snow capped mountains suggest the water comes from select, untainted sources. In fact, from 25% to 50% of the bottled water Americans buy is simply municipal tap water. Moreover, as any hiker can tell you, you need to filter out harmful microorganisms from mountain spring water just like any other source. Water sources that don’t require any treatment are rare, and as in the case of Hetch Hetchy Reservoir in Yosemite, which supplies San Francisco’s drinking water, they are not the exclusive source of private water labels.

Environmental groups also rebut industry claims that bottled water is healthier. While manufacturers tout the purification methods they use, the regulatory standard to which manufacturers are held is that of tap water. While consumers may worry about water picking up contaminants from municipal pipes, some studies suggest that plastic bottles could release harmful contaminants when stored for a long time. Tests by the Natural Resources Defense Council found, for example, that in one fifth to one quarter of the brands they tested, at least one sample was contaminated at higher levels than state laws or other guidelines.

The other reason that Americans spend millions on bottled water is one which Riese, who does not drink tap water, would support: taste. “Smell this tap water. It smells like chlorine,” Riese told the LA Times last year. “As a restaurant person here in L.A., I can say I would never drink that water. When you have good food, good wine and good spirits, you don’t want to contaminate that with this water.”

Taste is Tricky

Pools contain bacteria-killing chlorine so that you can keep swimming even as the kid at the other end secretly pees in the pool. Similarly, tap water contains trace amounts of chlorine as an insurance policy on clean drinking water. Municipalities generally concede that the taste of chlorine in tap water is potentially perceptible and not so pleasant; they also recommend getting rid of it not by spending over $100 per year on bottled water, as the average American does, but by letting water sit for a few hours in the fridge or buying a simple water filter.

But even without removing the taste of chlorine, Americans don’t seem to prefer the taste of bottled water over tap water once you remove the effects of brand names and expensive marketing campaigns. News organizations, public health commissions, and universities have all held blind taste tests with a mix of bottled water fans and tap drinkers. None has failed to find that people can’t tell which is which; all either found that people had no preference or preferred tap water.

As comedian Conan O’Brien puts it in the below segment while tasting waters under Riese’s supervision, “No! I don’t get anything! What do you taste?” Of the two waters O’Brien tries, one is 9OH20, Riese’s own designer water that “combines pristine spring water from the Northern California Mountains with carefully selected natural minerals to create a silky smooth, incredibly crisp taste.”

But you can’t simply dismiss Riese as a crank and call it a day, because there are taste differences in water. Waters have different levels of minerals present, which is why tap water tastes different when you travel. (As a child, Riese says he would taste the water constantly when his parents took him on vacation to check out the different tastes.) It’s these minerals that Riese points to as the source of water’s distinct flavors.

Environmental groups love to point to these blind taste tests as a sign that you should drink tap water over expensive, wasteful bottled water. But the tests actually tell us more about the fickleness of our tasting abilities than whether water can really taste all that different.

As Priceonomics has covered before, when people taste wine without knowing its price tag or brand, they’ll confuse red wine with white wine, name Two Buck Chuck California’s best Chardonnay, and confuse wines from France and New Jersey. That’s true of laymen and wine industry insiders alike, and our ability to discern high quality foods is just as surprisingly limited. This should make you think twice about paying 1000% markups for high quality wine and tuna, but it doesn’t mean you shouldn’t enjoy food and drink.

Why Designer Water Could Work

The question is whether the differences in water are so imperceptible that writing tasting notes — or doing anything other than running water through a filter — is completely ridiculous. On one hand, when we look at blind taste tests, Riese and premium water have just as much legitimacy (as measured by objective evidence) as award winning winemakers and fancy Bordeaux.

On the other hand, if someone has just drank coffee, Riese suggests they try a “water tasting” another day because it will be impossible to taste the different water flavors over the overpowering coffee taste. When Conan O’Brien eats a cracker during his water tasting to “cleanse his pallete,” Riese begs him not to. That’s a curious position given that Riese’s 9OH20 is designed for “perfect pairing with fine foods, fine wines, Scotch and other fine spirits.”

But that doesn’t mean that there is no chance designer water and H20 snobbery will catch on. Probably the best comparison to designer water would be premium vodka. As journalist Felix Salmon writes:

I am absolutely convinced, on an intellectual level, that the whole concept of “super-premium vodka” is basically one big marketing con. Vodka doesn’t taste of anything: that’s the whole point of it. As such the distinction between a super-premium vodka and a premium vodka is entirely one of price and branding. And yet, it works! The genius of Grey Goose was that it created a whole new category above what always used to be the high end of the vodka market — and in doing so, managed to create genuine happiness among vodka drinkers who spent billions of dollars buying up the super-premium branding. But if someone asks me what kind of vodka I’d like in my martini, I still care, a bit. And if I my drink ends up being made with, say, Tito’s, I’m going to savor it more than I would if I had no idea what vodka was being used.

The difference between high and low end vodkas, even, is generally the degree to which it makes you feel like you are dying. (This is not a slight; this author has enthusiastically attended vodka tastings.) It’s a difference that many believe can be simulated, like with tap water and “premium” bottled water, by running a cheap vodka through a water filter until it tastes almost like Grey Goose.

In both the vodka and water industries, marketing campaigns created a new market for a premium version of a beverage with barely perceptible differences — a characterization far more apt of water than of vodka. In both, the actions of customers have validated those products.

We do not want to see water turned into a premium product. The widespread, affordable availability of safe drinking water in the United States is a fantastic development that cannot be fully appreciated until you live somewhere (in the U.S. or abroad) without it; paying extra for an environmentally wasteful alternative seems silly. The vice chairman of PepsiCo, which makes Aquafina bottled water, once said, “The biggest enemy is tap water.” Another beverage industry executive has said, “When we’re done, tap water will be relegated to showers and washing dishes.” Treating branded water as special is the first step toward that.

The problem with mocking the water sommelier, however, is that Americans have already shown that they value water more when they have to pay for it — it’s an indefensible position for Americans to lambast Martin Riese while simultaneously spending over $9 billion on bottled water. The fact that a water sommelier exists is pretty funny. But the joke is on us.

This post was written by Alex Mayyasi. Follow him on Twitter here or Google Plus. To get occasional notifications when we write blog posts, sign up for our email list.