Ephemerisle 2009, (photo: Liz Henry)

About a hundred miles east of the Pacific Coast, the San Joaquin River and the Sacramento River collide with the east side of the San Francisco Bay. The result is a sprawling delta, as socially and politically fraught as it is beautiful. Dragonflies mate in its marshes, children wade, and vacationers fish, carefully avoiding the 800-foot cargo ships that slice like metal icebergs down deep-water channels from the bay. 40 miles northeast, in Sacramento, California’s congress hotly debates how to ration the state’s diminishing supply of fresh water.

Once every summer, for one week, the Delta gets even more surreal. A couple hundred people, many of them members of the San Francisco tech community, float a bunch of boats into one of the more spacious coves, drop anchor, and lash their craft together into “islands.” There, they form an ad hoc, quasi-techno-utopian society.

This is Ephemerisle: the strangest, most anarchic, boisterous and “buoyant” party-cum-libertarian-social-experiment on earth. The festival was started by people with the ultimate goal of floating free from California and its turmoil, from the United States and its economic regulations, and getting away from it all, literally.

Step 1 to Colonizing the Open Ocean: Throw a Festival?

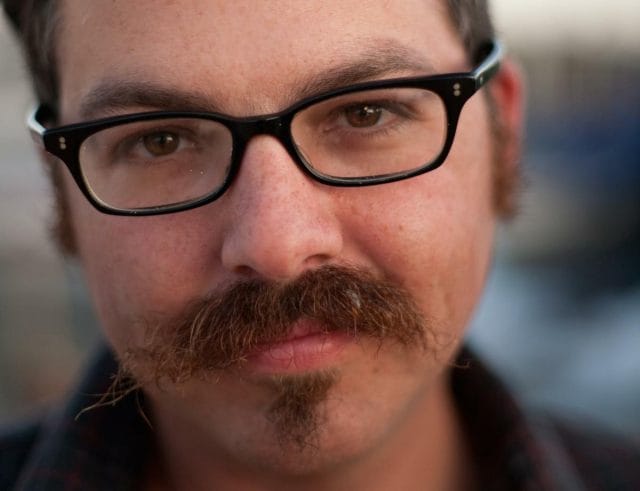

Patri Friedman, 2011 (photo: Hannu Makarainen)

Ephemerisle was the brainchild of Patri Friedman, a small-statured software engineer with a dark beard and bright demeanor, grandson to the Nobel-winning economist Milton Friedman. Milton Friedman was a famous advocate of classical liberalism, free markets, and small government. In the early 2000s, his grandson was in a graduate program in computer science at Stanford University, and had some pretty radical ideas about how to put his grandfather’s ideas into practice.

“I want to live in freedom,” he wrote, “(by which I mean at least libertarianism, if not anarcho-capitalism). Unfortunately, no such political system is implemented on a significant scale anywhere in the world.”

Thus, he concluded: “I am interested in helping to create a new libertarian country.”

There were, of course, obstacles to this goal. To Patri’s eye, one in particular stood out: “[A]lmost all land is controlled by governments, which tend to be very reluctant to give up sovereignty.” Like many before him, Patri looked to the ocean as his frontier.

If you’re a certain distance from the coast of any country, you’re in international waters. If the vessel you’re on is registered under a country’s flag, that country’s laws apply. If the vessel isn’t registered, most bets are off (with a few notable exceptions — laws against piracy still apply, for example). Boats in international waters have been used to circumvent regulations on gambling, surgeries, broadcast bandwidth, and more.

Although it’s been the ambition of many separatists, nobody’s ever been able to establish a sovereign state on the high seas. Of the attempts that have been made, none could have been called successful, (the closest call, the Principality of Sealand, was an old military fort off the coast of the UK, held by the family of a pirate radio DJ since the 1960s. The fort used to be in international waters, but the UK has since extended its territorial waters, technically annexing Sealand.)

That’s because seasteading, the establishment of permanent dwellings on the open ocean, is hard. A lot of things we land dwellers take for granted — not-drowning, charging a laptop, having food to eat today and tomorrow and the next day — become a lot more challenging on the open ocean. It should be no surprise that many, many people think seasteading is impossible.

Seasteading’s proponents say it isn’t impossible, it just has a funding problem: existing solutions cost money to implement, and the solutions that don’t exist yet cost money to develop. But even they admit it’s a hell of a funding problem. The funding necessary to launch even the simplest floating city was in the billions, leaving most proposed projects dead in the water, so to speak.

Still of a floating city in “Waterworld” (1995)

Patri dreamed up the festival, Ephemerisle, originally as an answer to that funding problem.

He was inspired by the writings of Wayne Gramlich, an older programmer and aspiring seasteader whose work Patri found online. Instead of planning elaborate floating metropoli, Gramlich proposed seasteading the ocean much like American settlers homesteaded the midwest: one by one, or family by family, on a budget. To this notion, Patri suggested another way to baby-step towards seasteading:

“[Previous seasteading] projects all suffered from too much ambition. They attempted to tackle a difficult problem all at once, rather than dividing it into realistically small pieces. Realistically small, for a country, may not merely mean space, it may also mean time.”

Patri had already witnessed one temporally limited proto-country: Burning Man, a massive, spectacular, week-long art festival in the desolate Black Rock Desert, Nevada. There, tens of thousands of people camp together in an ad hoc city of art, inclusion and radical self-expression. The feats of engineering, social organization, and creativity that tens of thousands achieve, given one a week in a wasteland chemically incapable of supporting life, inspired Patri. It also struck him as a potentially “harnessable force.”

Perhaps, Patri thought, he could throw a festival like Burning Man on a temporary seastead in international waters. It could be a “raft-up” — attendants could boat out to the event and lash their vehicles together to make a large, artificial island. Because the “island” would only exist for the duration of the festival, Patri named it “Ephemerisle,” a portmanteau of ephemeral and isle.

Unlike Burning Man, where participants are still subject to the laws of the United States, Ephemerisle would offer attendants true autonomy from American government. Also unlike Burning Man, which bans cash transactions between participants at the event, Ephemerisle would embrace money and commerce, as a respected feature of society. And also unlike Burning Man, Ephemerisle would be unticketed, free to anybody who could get there.

If people liked the festival enough, Patri thought, they might start staying out there for longer year after year, and invite their friends. It would grow both temporally and in population. For that to happen, the island itself would have to grow, too. Over time, maybe these people would be motivated to solve a lot of seasteading’s hard engineering problems, so Ephemerisle could continue to grow. As Patri later explained his thinking:

“If there was some difficult but solvable technical problem that those people had to solve that to get Burning Man to a place where they didn’t have to pay a large portion of ticket fees, […] [and] where they didn’t have U.S. legal requirements, could that community of […] amazing builders and creators […] solve that problem? Hell yes.

That community of inspired enthusiastic people, they could solve a technical problem, no problem. […] They solve a lot of really tough problems because they’re inspired to do so.”

Patri bought “ephemerisle.com” in 2001, and “seasteading.org” in 2002 (he has said of Ephemerisle, “One third of the reason why I wrote all of this down and put up a website about it is because I really like the name.”) For a long time, not much happened. He reached out to and befriended Gramlich, who also happened to live in the Bay Area. In 2002, the two of them floated a few homemade crafts onto Patri’s pool and called them “poolsteads” (“Might stick a plant or two on top just for fun.”)

Then, half a decade later, Patri and Gramlich met Peter Thiel.

The Vision Meets the Money

Seasteading Contest Winner András Győrfi’s design for a modular seastead

Patri was, and still is, a man of many blogs. He’s blogged about everything and anything: seasteading, fatherhood (he has two children), romance, libertarian politics, novels, and nutrition. In 2007, he announced that he and Gramlich were working on a book on seasteading. Eventually, his blogs found their way to the screen of an independently-minded libertarian venture capitalist, bent on funding ideas most sane people thought were crazy.

Enter Peter Thiel. The year is 2008. Thiel was a founder of PayPal, an early investor in Facebook, and a founder of the venture capital firm Founders Fund. Founders Fund specializes in “revolutionary technologies,” claiming in its manifesto that VC culture’s shift to “incrementalist investments” has held back innovation. “We wanted flying cars,” they write, “instead we got 140 characters.” In 2008, Thiel himself had funded anti-aging research via the Methuselah Foundation, and the Singularity Institute, (which would later become the Machine Intelligence Research Institute: MIRI).

Patri and Gramlich had not made much technical progress on seasteading since 2001, but their thinking on the subject had significantly developed. Patri and Gramlich envisioned a future in which thousands, if not millions, of artificial islands dotted the oceans. Their idea was that archipelagos of these micronations would increase market competition between governmental systems, and lower the cost to an individual leaving a system they didn’t like:

“Rather than adapting policy to voter preferences, local governments can keep policy constant and allow consumer-citizens to adopt whichever bundle of services best matches their preferences. If consumers can vote with their feet, local government planners do not face the same information deficit as central government planners.”

Patri and Gramlich theorized that this competition for citizens would drive up the quality of governing systems, and allow people better and more granular choices. They even suggested the islands could be designed so that individuals who wished to change affiliation could just untie their house and the “land” it was built on, and float away.

Apparently this vision fell into the category of “flying car” visions of the future. Thiel, Gramlich, and Patri met, and Thiel invested $500,000 for the partners to found the Seasteading Institute. Thiel’s eventual total investment in the Seasteading Institute was a reported $1.25 million in 2011.

Poke around the Seasteading Institute’s website and you’ll find “8 Moral Imperatives” to make seasteading possible. Whether or not you believe their claims, seasteading — or at least its rhetoric — had gone from one man’s heart’s desire to help start a libertarian country, to a philanthropic cause to save the world via its economies.

“It is a way for people to unilaterally bring about change and make the world a better place,” Peter Thiel said in 2009 as the keynote speaker at the first Seasteading Conference.

And part of that mission was Ephemerisle.

Although Patri said most of those resources were going towards a “top-down approach” — investing in businesses and engineering research — Ephemerisle remained part of the plan. “We see it as a parallel, cheaper, bottom-up option,” he said in at the first Seasteading Conference, days before the first Ephemerisle, “that reduces our risk by having it in our portfolio.” In addition to trying to architect and engineer the world’s first floating countries, the Seasteading Institute started planning a big, floating party.

The Man Who Made Things Float

Chicken John Rinaldi at the first Ephemerisle, 2009 (cropped photo: Christopher Rasch)

“Patri is a slick little shit, isn’t he?” San Francisco artist Chicken John Rinaldi tells us. “Swindling millions of dollars for absolutely nothing.”

Chicken John is the man who built the first Ephemerisle. When planning the event, Patri asked his friends in the Burning Man community a lot of questions about how to organize a festival. He was also asking people whether they knew anything about boats, about floating platforms, about camping for extended periods on water.

And he kept getting the same answer: “Well, I don’t know. Call Chicken John!” At least, that’s what Chicken John says.

Chicken John was a member of the famed Cacophony Society, the artists, street artists, and performance artists who organized the first Burning Man, and the first Santacon. In 2007, he ran for mayor of San Francisco, telling the Chronicle, “The government should be like someone you want to invite to the party, not someone you would call to do your taxes.”

Chicken John knew a thing or two about boats, because of a series of collaborations he did from 2006-2009 with street artist Swoon. “Swoon makes boats,” Chicken John wrote of the projects. “Well. She causes boats to be made. Like static electricity causes lightning and thunder.”

The premise was simple. Swoon would design towering Winchester mystery structures out of trash and scrap. She and her friends, including Chicken John, would voyage on and live on them for months at a time — part as art, part as an experiment in communal living, and part just for fun. Chicken John’s job was to stick recycled motors on the junk boats, make them go, and make sure they didn’t sink.

“I knew what I was doing, I’m a mechanic,” Chicken John tells us, about starting the project in 2006. “But I didn’t know how anything floated, I had no idea. Nothing. From nowhere.”

He learned. They took their first boats down the Mississippi in 2006 and 2007, and another fleet down the Hudson in 2008. “Eventually we packed them all in shipping containers, and then floated across the Adriatic Sea,” Chicken John says. On that voyage, they took their craft 250 miles from Slovenia to Venice. “We crashed the Biennale while Yoko Ono was getting her lifetime achievement award.”

One of Swoon’s Swimming Cities, docked (photo: RJ)

When Patri approached him in 2009, Chicken John might have been the world’s leading expert on the mechanics and perils of doing weird stuff on the water, including living on it. He was also a self-described rich, white Republican, which might have made him seem more culturally approachable to the likes of Patri and Gramlich. Patri commissioned him to build Ephemerisle 1.0’s central platform.

“I was like, sure, I’ll do your project for you,” Chicken John says. He says he thought the seasteading aspect of the festival was “for fun,” or “funny,” and didn’t know the seasteaders were serious when he agreed to work with them. “Anybody who says they’re going to build seasteads on the open ocean is an asshole and a swindler. Yeah, sure we’re gonna build seasteads on the ocean. And then the moon!”

When Chicken John joined, Patri had already changed his position on what qualified as a “realistically small” first version of the festival. They were still going to start small in terms of duration and population — 100 people, one weekend. But given the state of seasteading technology, and the dearth of practical nautical experience within the institute, (“The prototypical seasteader was a nerdy tech entrepreneur,” Patri told us), debuting the festival on international waters was deemed too ambitious. The first Ephemerisle had to take place somewhere with calm waters, predictable weather, and easy access.

They chose a spot on the San Joaquin-Sacramento River Delta called “Disappointment Slough.” It was close to a marina that often rented out houseboats, designed to be lashed together for large parties. “It’s very common to tie boats together like that,” Chicken John says. “It’s the best way to anchor a bunch of boats close together — if you anchor them separately, the waves smash them together and you damage the boats.”

The boats weren’t designed for large waves, which is something the Seasteading Institute hoped to figure out in later years, as international waters were still on Ephemerisle’s roadmap. The second Ephemerisle was to take place on the San Francisco Bay, one year later. “After that,” he had said, “this is a big step that may take more than one year, we’d like to take it to the coast. […] And then, the ocean.”

Ephemerisle 1.0

Ephemerisle 2009 (photo: Christopher Rasch)

The first Ephemerisle was documented in an eight minute video by Jason Sussberg — at the time a Stanford MFA student in film. About a hundred people showed up on eight houseboats, which they eventually lashed to Chicken John’s platform. There was food, drink, dancing and general revelry. As Reason Magazine’s Brian Doherty claims in the film, it delivered on its main promise: “There’s a central space, 100 people are on it, enjoying themselves, most of the little things are docked to it.”

But there was also a lot that went wrong — things went over budget, and building the island and its platforms took twice the time expected (“We have a lot of optimists here,” someone observed, as construction that was supposed to be complete Friday morning continued into Saturday.) Merely anchoring a single boat in a current proved more challenging than expected.

The film ends with a shot of Patri on a derelict ship, soberly recapping the weekend’s lessons. “I think I have a better idea now of just how hard […] the ocean is,” he says to the camera. “[Water] makes everything more difficult, it makes everything more expensive, it makes everything take longer. I think seasteading is still worth going after in spite of that.”

Doherty also brings up a criticism in the film: “I’m not entirely certain I can see the throughline between this and the end of seasteading goal. Seasteading has to involve economic activity, and this is not that. You’re like building a cult around seasteading! This is great! We’re all in this together-”

Lonely Island’s “I’m on a Boat!” starts playing in the background, and Doherty starts laughing and drops the rest of his sentence. “And the dance party has begun!” he says, waving a can of PBR at a group of people singing atop a houseboat.

Chicken John at the first Ephemerisle, (still from Jason Sussberg)

All the shots of Chicken John in the 8 minute film are of him working. “There’s not a lot of people here that are very salty,” he says in one clip, meaning nobody there knew much about being on the water.

“They basically spent a bunch of money on a weekend camping trip and it failed miserably,” he tells us, of that first year.

According to him the build was even more difficult than the documentary conveys. He had to enlist help from the local marina just to cart his materials out. “I thought that Patri and his community would provide me with people to help me out,” Chicken John says. “And then it was just me.” When the weekend was over, seemingly through further mismanagement, he was abandoned at Disappointment Slough:

“I had one guy helping me out. And Monday morning that guy was gone. He was gone, his houseboat was gone. They just left me with this giant platform. And, honestly, it was scary. What happened if I dropped my cellphone into the water? There was nobody fucking there.”

Chicken John also says he fronted all the money for the platforms, and then had to push the Seasteading Institute to reimburse him. “It made me violently ill,” he says. “If I was 20 instead of 40, I would have beat them to an inch of their fucking lives.”

Ephemerisle, Today

The chandelier boat

Six years later, Ephemerisle took place from July 20-26, 2015. In total there were an estimated 500 attendants, and the official event lasted seven days. Many participants were out there for ten, building up and taking down “islands.”

A 130-foot 1930s research vessel attended, as did a barge carrying a two-story RV covered in LEDs, and another with a DJ booth and a 10×2 grid of speakers. Ferries ran between islands throughout the weekend, some of them imaginative “art boats.” One was a small dance barge, “The Artemiid,” with a shade-structure that made it look like a giant nudibranch. By day, it shed and collected swimmers, and its fins rippled in the headwind when riders tugged on certain ropes and levers. Another art boat was a small dinghy, with a chandelier that dangled like an angler fish’s lantern. Another art boat was a Delorean chassis modified into a hovercraft.

The Delorean (still from Oceanus)

The event has grown in many of the ways predicted — it’s larger, grander, and lasts longer. But, even in its 6th year, Ephemerisle did not take place in the open ocean, nor just off the coast, nor in the bay. It still hasn’t made it out of the Delta it started in.

“I think the ways Ephemerisle has grown are the easy ones,” Patri tells us. “It’s still too early to tell whether it’s on the incremental trajectory to seasteading. Like, in some ways, it’s been really successful. But it also doesn’t look like it’s developing into autonomous independent communities for a week a year.”

The Seasteading Institute never sponsored a second Ephemerisle. Having gone uninsured the first year, they officially cancelled the event in 2010 when they couldn’t find insurance less expensive than $300 per participant. The community decided to have a party on the planned weekend anyways, under the name “Not-Ephemerisle.” They moved it a few miles to a cove called Mandeville Tip, where it is still held today. In 2011, the Seasteading Institute officially handed the event over to the community.

Patri left his position as president of the Seasteading Institute in 2011 to pursue a “Free Cities” project in Honduras. He’s now back in the Bay Area, working at Google again, and chairman of the Seasteading Institute’s board. He says the Seasteading Institute has refocused its efforts solely into more top-down, “less speculative” ventures.

“Over time, we’ve come to the viewpoint that we want to work with countries,” he says. “You have to be really big in order to actually start your own country.”

But even though the Seasteading Institute is no longer officially involved, it’s not clear that Ephemerisle is far off-track on the route to seasteading. The road might just be exponentially longer, and much murkier than Patri expected.

The Robert Grey at sunset (still from Oceanus)

One example of possible progress towards seasteading was Project Oceanus. They rented out the Robert Grey, a 130-foot, 1930s research vessel, and hosted daytime talks and night-time dance parties. Project Oceanus is in the process of acquiring 300 foot ship to fix up and turn into a live/work space on the San Francisco Bay. Their plan is, ultimately, to pilot it to the Pacific Garbage Patch and 3D-print the plastic into the foundation for a floating city.

Another example of progress is that, year to year, the community has built up nautical expertise. The Ephemerisle github and wiki are both chock-full of documentation: recaps on what worked and what didn’t year to year, diagrams on how to anchor a raft-up, or how to build a platform. Organizers say that they’ve been prototyping build designs in calmer parts of the San Francisco Bay during the year, and a Bay-based festival might not be far off.

This year, about 65% of the population of the festival stayed on an archipelago called “Elysium.” In Elysium, long narrow bridges made out of plywood and inner tubes connected small satellite groups of houseboat islands, and one sailboat island, to other floating platforms: a dance floor, a few platforms designated for lounging or meditation. Such a structure wouldn’t even have been conceivable in 2009. When Patri and his partner ferried in this year, this is where they stayed.

Elysium is run by Simone Syed and Scott Norman, managing partners at Velorum Capital (they are also a couple). Although Syed does not identify as a seasteader, she was brought to Ephemerisle in 2012 by friends in the community. Syed was horrified by the unsafe conduct of some of the attendants. (This included a young man who freaked out on acid, stripped naked, and sprinted away from the Coast Guard — first by swimming, and then, when he reached the shore, on foot. This year, Elysium held a race in his honor.) At first, Syed was so upset she resolved never to attend Ephemerisle again.

“But the people who come to Ephemerisle are some of the most brilliant people on the planet,” Syed says. “It would be a travesty if any of these individuals perished in an accident we could have prevented.” So she changed her mind, and decided to run her own island the next year, as a safety-first dictatorship:

“My friends and I realized we could create our own island nation state, and our own form of governance. The people we wanted to participate with us would buy into those rules. We ended up being the biggest island, the party island, but we had instilled a sense of personal responsibility in each of our crew members.”

Part of Patri’s original vision for Ephemerisle was that, while Burning Man celebrated artistic expression, Ephemerisle would celebrate “political” expression. Instead of art, people would build their own toy systems of governance — maybe one boat would merely permit nudity, for example, and another would require it. People could “vote with their feet,” in a toy way, and hang out at the boat with the best legal system for their immediate needs.

Syed’s decision to run her own island as a “benevolent dictatorship,” on the water went above and beyond that vision. And her emphasis on safety measures, and her relative willingness and ability to enforce them, might have legitimately saved the festival from disaster. Her partner, Norman, took over Elysium’s infrastructure, its engineering and architecture. As the leaders of Ephemerisle’s largest island, Syed and Norman are now the closest thing the festival has to head organizers.

Sunrise on the Delta

Syed says she doesn’t see Ephemerisle as a festival: her preferred label is “family gathering.” Though there were hundreds of people on her island alone, each boat was managed by one of her close and trusted friends. She sees the event as a community strengthener for people within her network. “I actually don’t go to Burning Man anymore,” she says, “because I would rather spend my time getting my archipelago situated.” Participants bond in a relatively isolated setting, in relatively close quarters, over challenging collaborations. They’ve learned to look out for each other.

As for Chicken John, who was abandoned at Disappointment Slough, he still comes every year. “To watch them fail,” he claims. “It’s hilarious.”

He patched things up with the community in 2010 when they helped him acquire his own houseboat — a flat-bottomed, 1940s “potatoe barge” that “looks like Popeye’s house.” He also runs his own, ticketed, floating festival, Camp Tipsy on Lake Ladoga, where people build and camp on Swoony structures. Now, in the weeks leading up to Ephemerisle, he makes a point of scanning the Facebook groups for people who need nautical advice. “I respond if I think I have anything I can add to be helpful,” he says. “Or zings. I’m there to zing. I’m a zinger. All in good nature.” He does the same at the festival itself, walking around, talking to people, tightening loose screws, helping where he can.

“I know Chicken,” Patri tells us with affection. “He’s kind of a completely insane and amazing person.”

The Purpose of the Party

Chicken John also raised the important question: The world clearly has many problems, which it will take a lot of work to solve. In the absence of a clear path to utopia, should people still spend their energy and resources on a party like this?

“It’s probably good that things like Ephemerisle keep happening, even if they’re failures,” Chicken John says. “But you’re looking at $60-80,000 in rented equipment there. It’s a lot of money — we could go buy 100 derelict boats. Or have a piece of property in the Delta and throw the party there. Or we could give the money to a battered women’s shelter. Or we could have a party for one night.”

“I don’t know, I’m one to talk. I just went on vacation to Cape Cod,” he adds. “It confuses me. I’m from the junkyard, I’m not from the silver spoon.”

The point certainly warrants consideration. A popular theory of innovation is that “the next big thing always starts out being dismissed as a ‘toy,’” as Chris Dixon put it. The idea is that truly disruptive technologies “undershoot user needs” at first. They get called toys because nobody knows what to make of them. But after a point, the technologies begin to develop much more quickly than the needs people know they have. That’s how a technology transforms a society, it solves the problems people never imagined technology could:

“The first telephone could only carry voices a mile or two. The leading telco of the time, Western Union, passed on acquiring the phone because they didn’t see how it could possibly be useful to businesses and railroads – their primary customers. What they failed to anticipate was how rapidly telephone technology and infrastructure would improve.”

Some toys, on the other hand, stay toys. Today, Ephemerisle is still in its toy stage. And like Patri said, “it’s still too soon to tell,” whether it’s building towards something greater. We’ll just have to wait and see.

This post was written by Rosie Cima; you can follow her on Twitter here. To get occasional notifications when we write blog posts, please sign up for our email list