It’s hard to think of a greater constant throughout history than how mothers feed their newborn babies. Across cultures and times, babies have relied on their mothers’ milk for nourishment.

Alternatives have always existed. Families employed wet nurses or modified animal milk for babies whose mothers could not breastfeed, chose not to, or died during childbirth. And beginning in the late 19th century, companies began producing infant formula, a standardized modification of cow’s milk meant to resemble breast milk. But the alternatives were more of an exception than the norm.

In a relatively short period from the early 1900s to 1970, however, mothers opted en masse to bottle feed — first with homemade modifications to animal milk and later with standardized formulas like Similac of Abbott Laboratories and Enfamil of Mead Johnson & Company. By 1972, only 22% of American mothers breastfed their babies.

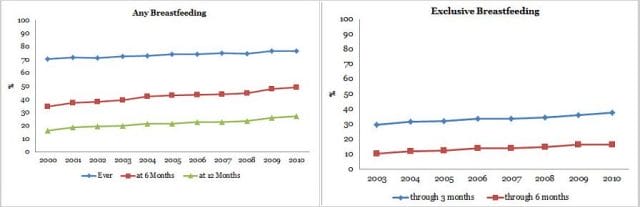

This sudden change in something as fundamental as how parents feed newborns only took two generations, yet it nearly reversed in equally short order. The number of breastfeeding mothers rose steadily beginning in the mid seventies to almost 60% of mothers in 1982 and, after a brief decline, around 70% today.

On one hand, the story of how parents chose to feed their newborns infant formula and the switch back to breastfeeding is that of a growing medical consensus about the benefits of breast milk and a refutation of manufactured alternatives’ ability to match nature’s formula. (The arrogance of thinking that science could do in 40 years what nature perfected over millennia, as some doctors have put it.) Today the healthcare industry extols the benefits of breastfeeding, which are taught in medical curriculum and promoted by major public health initiatives.

But the sudden change in baby nutrition resulted from more than the conclusions of the medical profession. Economic forces, health fads, and marketing played leading roles not only in the decisions made by parents, but also seemingly in the recommendations and conclusions of medical professionals — a reminder of the susceptibility of even a question as important as how best to raise healthy babies to something other than a scientific process.

“Breast is Best”

During consultations with medical staff and from helpful pamphlets, expecting parents learn about the benefits of breastfeeding over using a commercial formula approximation. Breast milk is the ideal nutrition for infants — easily digestible and leading to correct weight gain, with many more ingredients than formula including antibodies to boost babies’ immune systems. Breastfeeding leads to fewer doctors visits and reduced risk for problems like ear infections, diarrhea, asthma, and respiratory illnesses. It helps mothers space births, lose pregnancy weight, and bond with the newborn. It’s even linked to higher IQ scores.

If all that is difficult to remember, advocates use the more memorable phrase “Breast is best.”

Despite the avalanche of medically advocated benefits, new parents usually leave American hospitals with a discharge bag full of free samples of branded infant formula — although the formula starter packs dutifully declare that “breast is best” alongside their pitch for the value of their product.

Breastfeeding advocates bristle at hospitals’ compliance with this “marketing” tactic of giving out free samples. Many women need formula due to prescription drug use or illness, or because trouble with the process renders them unable to breastfeed. And all but the strongest breastfeeding proponents note that the choice belongs to mothers, who may prefer using formula to allow others to feed the baby, due to difficulties breastfeeding, or to avoid personal discomfort. But advocates see these samples as lending an imprint of medical approval to formula that inhibits progress toward goals like the 82% rate of breastfeeding targeted by the United States Breastfeeding Committee.

In addition to efforts to ban these sample bags from hospitals, efforts to increase breastfeeding rates include public awareness campaigns including “Breast is Best” television and print advertisements by the US Department of Health and Human Services (HHS), advocating workplace protections for breastfeeding mothers like longer maternity leave and breaks to pump milk, and pushing to make breastfeeding in public socially acceptable (as it’s extremely difficult to breastfeed every few hours when it is seen as indecent).

It is not simply a battle between formula companies and mothers. The push to increase breastfeeding rates also inspires strong feelings. Many mothers resent the perceived message that feeding a baby formula makes them negligent mothers.

One TV ad from Health and Human Services begins with a pregnant woman riding a mechanical bull. She then falls as the screen reads, “You wouldn’t take risks before your baby is born, why start after? Breastfeed exclusively for 6 months.” A voice then lists off some of the benefits of breastfeeding.

One mother wrote online in reaction:

I wish there was a way to sue the pants off of them for putting that on the air. That commercial probably just made some poor woman, that’s sitting there trying to breastfeed, no milk coming out, her nipples bleeding, and her starving child screaming, cry her eyes out. Assholes.

Despite the huge move toward a return to breastfeeding, practice remains divided between breastfeeding and using formula. While 70% of American women now breastfeed at some point according to the Center for Disease Control, that number has remained fairly flat over the past decade. Further, under 50% of women breastfeed through six months and only some 15% of women breastfeed exclusively as advocated by the World Health Organization.

Percentage of children who were breastfed, by birth year. Source: CDC

From Wet Nurses to Nestlé Good Start

Although today’s mothers mainly choose between breast milk or a formula made by a company like Nestlé or Gerber, alternatives to nursing have a long history.

From BC times until the 19th century, the main alternative was a wet nurse — a woman who would nurse someone else’s baby after giving birth herself. Although often found through social networks, in many times and places, wet nursing could be a solid profession, often regulated by governments to make sure women were healthy and not neglecting children of their own. Although in other times, including in early America, slaves were forced to serve as wet nurses for their masters.

In different places and times, people also used foods ranging from animal milk to options like the Greek preference for wine and honey to supplement or replace breast milk. Families used wet nurses or other foods when a newborn’s mother died during childbirth, when an upper class woman did not want to breastfeed for social reasons, or when women needed to work.

In the 1800s, using animal milk (known counterintuitively as “dry nursing”) replaced wet nursing as the primary option in the U.S. and Europe. Different designs of cups rose and fell in popularity, aided by the invention of the rubber nipple in 1845, until the glass baby bottle became standard.

Doctors noted that dry nursed babies suffered from cases of diarrhea and other problems that proved fatal at their young age. Spoiled milk and unclean feeding vessels led to mortality rates as high as ⅓ among non-breastfed newborns in the early 1800s. Although the cause was not fully understood until the development of germ theory, the newly created field of pediatrics sought to correct the situation. Chemical analyses of breast milk led to the creation of additives and formulas to make cows milk better resemble breast milk, and companies created the first mass produced formulas with pediatricians’ support in the 1860s and 1870s.

Although commercial formulas appeared on store shelves and in commercials in the 19th century, modified animal milk remained more popular. Most parents found the nearly $1 per can formula too expensive.

Breastfeeding alternatives grew safer thanks to pasteurization, refrigeration, and understanding of hygienic practices to protect newborns from spoiled milk and bacteria. In the 1920s and 1930s, studies showing that dry nursed children fared just as well as breastfed children made doctors and parents confident in the use of these alternatives. Doctors showed patients how to modify animal milk until the ease and lowered cost of commercial products led to their widespread use in the fifties. No exact data on breastfeeding rates exists before the 1950s, but sources report rates declining until by 1972 only 22% of American mothers breastfed.

“Ethical” Marketing

Given that the “breast is best” message is delivered through a bullhorn by medical associations and public health groups, we imagined doctors and formula companies butting heads over the marketing and distribution of baby formula. But for fifty years, formula companies marketed (and often distributed) their product exclusively through doctors.

Physicians expressed concern about companies advertising food for newborns in the late 1800s due to the high mortality rates seen among bottle fed babies. This resulted in a preference for breast feeding, but also a push by doctors to lead the charge for cleaner milk supplies and doctor oversight of the feeding process. Physicians began preparing breast milk alternatives in hospitals and recommending that parents make frequent trips to the pediatrician’s office to oversee the feeding process.

In 1912, Mead Johnson & Company deferred to pediatricians’ careful protection of their oversight role and unveiled a formula at an American Medical Association meeting. Brochures given to doctors stressed that “the physician himself controls the feeding problems,” deferring to their expertise, and the formula containers allowed doctors to write in their names on the label with a reminder to visit their offices regularly. Writing in the American Journal of Diseases in Children, Doctors Greer and Apple note:

Mead Johnson began a trend in the industry by deciding that gaining the respect and goodwill of the medical community could be potentially more profitable than marketing the product directly to the public.

For decades, companies followed this script of marketing products through doctors who they hoped would recommend their formula or provide initial samples to new mothers. Companies provided free samples to doctors and hospitals (often providing funding in exchange for exclusive contracts), funded doctors’ conferences, nutrition research, and social events, purchased advertisements in their medical journals, and presented at medical conventions. The American Medical Association often gave out its “Seal of Acceptance” to formulas in response.

This approach, known as ethical marketing (“apparently without a hint of irony,” as one academic notes) for its aversion to advertising directly to parents, persisted as the almost exclusive means of advertising baby formula in the U.S. until 1989. Despite questionable sales tactics practiced by the formula companies, such as sending female sales representatives in nurse uniforms to maternity wards and newborn mothers’ homes to dispense mothering advice while promoting infant formula, the cooperative agreement did not end due to doctors’ unease. Instead, it ended when Nestlé, which had no market share in the United States formula market, decided to advertise to the public due to its inability to break other brands’ stranglehold on exclusive hospital contracts and doctor recommendations.

Instead, the first backlash to the promotion of baby formulas over breastfeeding in Europe and the United States occurred in response to actions far from home. The rise of formula created a billion dollar industry, but the end of the post-war baby boom sent companies abroad in search of profits.

When they did so in impoverished countries, they faced the same unhygienic conditions that led to high mortality rates among non-breastfed babies in the United States in the 19th century. Mothers buying formula lacked the knowledge, means, or access to clean water (to mix with the formula powder) and bottles. Or they diluted formulas with extra water when they could not afford enough, leading to malnourished babies.

In 1974, an antipoverty organization called War on Want published an investigation into the promotion and sale of formula products in the third world entitled “The Baby Killer.” While the companies protested that they intended the product for urban mothers capable of using it safely, the investigation charged that formula companies targeted hospitals where formula caused infant deaths and created ads to convince mothers that their breast milk was insufficient. One radio jingle for a product called KLIM that aired in the Congo in the 1950s went:

“The child is going to die

Because the mother’s breast has given out

Mama o Mama the child cries

If you want your child to get well

Give it KLIM milk”

Awareness of the problem led to outrage among the American and European public, a boycott of Nestlé — the most publicly prominent manufacturer of infant formula, and the creation of the International Code of Marketing Breast-milk Substitutes by the World Health Organization that called on countries to pass legislation controlling the marketing of formula and promoting breastfeeding as the best approach to feeding newborns. It called for formula companies to note the superiority of breast milk in all their materials.

After years of enjoying the favor of the medical community and acceptance by the majority of the public, formula providers found themselves distrusted and at odds with public health initiatives to promote breastfeeding.

A Medical Tale?

The boycott of Nestlé in the 1970s coincided with the beginning of an uptick in breastfeeding rates until a majority of women breastfed in the U.S. — even if they supplemented with formula. But while a public health crisis incited the backlash against formula in developing countries, the roots of the return to breastfeeding had less medical origins in the United States.

In the late 1800s and early 1900s, when doctors noted the link between alternative nursing methods and poor health among newborns, they focused on the problem of the general public and private companies (rather than medical staff) overseeing the development and preparation of infant formula. This is probably due to both:

1) Pediatricians desire to assert the importance of their newly created pediatrics specialty and to ensure regular business for themselves as expert preparers and providers of formula (as some critics charge) and

2) Their belief that formulas needed further development (and the later realization of the importance of preventing bacteria buildup).

Formula companies played into this desire for control through their “ethical marketing” practices.

As bottle feeding grew in popularity, doctors did know that breast milk was the best choice for babies. After all, they sought to make alternative nursing methods approximate breast milk. But doctors sought to improve the safety of formula rather than eradicate it. (After all, formula is not a choice for all mothers.) A 1925 report from the American Medical Association accepted that the industry would exist: “It is impractical at the present time to dispense entirely with all proprietary foods.” It did note “the dangers of artificial feeding” and the benefits of breastfeeding, but focused on the problem of formula “carried out without the supervision of medical men.”

So despite criticism of artificial alternatives, when formula makers bowed to doctors’ desire for control and studies in the 1920s and 1930s showed babies fed formula fared as well as breastfed babies, most doctors accepted these alternatives as safe and acceptable. The full medical literature on the benefits of breastfeeding that bombards new parents today is a more recent development that uses regression analyses to discover benefits of breastfeeding that are not plainly obvious. In contrast, doctors at the time were responding to a history of bottle feeding as bacteria-laden death traps that led to a mortality rate of ⅓ at one point in the 1800s.

The tarnished reputation of formula makers pushed women away from nursing alternatives. Theories about bonding with newborns helped pull mothers toward breastfeeding. Organizations like La Leche League International had long advocated and supported breastfeeding. While they learned about medical benefits from supportive doctors, they trumpeted the importance of mothers and children connecting emotionally from breastfeeding. In the 1970s, Dr. Fentiman writes in an article, “Marketing Mother’s Milk,” a theory of “bonding” through breastfeeding gained popularity among child-rearing experts. “It offered a quick fix to complex medical and social problems,” she writes, as it was, for example, seen as preventing child abuse. Although not the stuff of case studies and medical trials, ideas of the emotional connection helped make breastfeeding resurgent.

The rise of breastfeeding from the mid seventies to today, as well as its previous decline, also seem to match a zeitgeist and respond to economic forces more than medical consensus. In The Atlantic, Hanna Rosin writes of formula appealing to her Israeli parents’ aspirations “to be modern”:

Nestlé formula was the latest thing. My mother had already ditched her fussy Turkish coffee for Nescafé (just mix with water), and her younger sister would soon be addicted to NesQuik. Transforming soft, sandy grains from solid to magic liquid must have seemed like the forward thing to do. Plus, my mom believed her pediatrician when he said that it was important to precisely measure a baby’s food intake and stick to a schedule.

During a time when technology delivered higher living standards and canned goods and just add water mixes made cooking more convenient, formula seemed like a similar triumph of science. And just as women aspired to be modern working women (or needed to), it freed them from the necessity of bi-hourly feedings that would keep them in the home.

Fast forward to the late seventies and especially the 2000s, and the move away from infant formula dovetails with social trends: The rejection of canned goods and genetically modified foods in favor of organic and all-natural. The parenthood mantra of whatever is best for the child (even if that means the often difficult process of breastfeeding).

This recent, controversial TIME cover captured the (often criticized) way in which commitment to breastfeeding has become a yardstick for a mother’s devotion in some mothering circles.

This all leads to the uncomfortable realization that the switch to infant formula and then the push to return to breastfeeding had less to do with a careful medical consensus and more to do with social and economic trends.

The Science We Want to See

Despite the consensus that breast milk is the best possible nutrition for infants — advised for all mothers who can breastfeed — a number of dissenters argue that its benefits have been overhyped.

In The Atlantic, Rosin writes:

One day, while nursing my baby in my pediatrician’s office, I noticed a 2001 issue of the Journal of the American Medical Association open to an article about breast-feeding: “Conclusions: There are inconsistent associations among breastfeeding, its duration, and the risk of being overweight in young children.” Inconsistent? There I was, sitting half-naked in public for the tenth time that day, the hundredth time that month, the millionth time in my life—and the associations were inconsistent?

After reviewing medical articles and finding a pattern of studies concluding that breastfeeding is “probably, maybe, a little better,” but also articles finding no benefits and flaws in studies that do, Rosin asks why the popular literature mentions none of this uncertainty and why she and so many mothers have become “breast-feeding fascists” over what seems like no more than minor benefits.

Studies and literature reviews like the 2001 article Rosin cites make up the ammunition for works including Joan Wolf’s book Is Breast Best? The primary complaint of skeptics like Wolf, drawn from reviews of breastfeeding studies published in medical journals, is that they struggle to control for context.

Breastfeeding rates are higher among wealthier women, who are more likely to have healthier infants due to their access to health care and better resources. Detailed regressions might still fail to account for all these factors, meaning that the benefits of breastfeeding might mostly reflect the benefits of an upper middle class upbringing over an impoverished one. Wolf and her fellow critics also draw from experimental evidence, such as studies comparing the outcomes of siblings who differ in whether they were breastfed or not, that don’t find many of the benefits found elsewhere.

The other major criticism of the breast is best consensus is that advice on breastfeeding’s benefits fail to give mothers a sense of the magnitude of the benefits. On an individual level, are the benefits significant? Or are they less impactful than some extra servings of vegetables or more helicopter parenting? Without this context, the formula or breast milk decision may not be a very informed one.

It seems that the popularity of breastfeeding and the way it fits into the current craze for all things organic and natural may bias the interpretation of scientific findings about breast feeding. We can see how scientists can “see what they want to see” by looking at examples in other fields.

In an article explaining why he “changed his mind” on medical marijuana use, Dr. Sanjay Gupta explains how the stigma of weed’s classification as an illegal substance (made more on the basis of its counterculture roots than medical findings) slanted the medical literature toward negative findings and prevented studies of its positive possibilities.

Science has long seen an evolutionary explanation for male animals’ (and humans’) promiscuity and the other gender’s chasteness. But in another example of how social forces sway scientific findings, new work suggests that no such (evolutionary) tendency exists among animals or humans. Instead, scientists interpreted and theorized according to victorian understandings.

Anthropologist Katherine Dettwyler pointedly shows how social forces impact advice on breastfeeding. Dettwyler advocates nursing children older than 2 years old, if desired by the parent and child, and based on comparisons with other mammals, she believes the natural nursing age for humans may be from 2.5 to 7 years.

Given the findings of breastfeeding’s benefits until age two, Dettwyler argues, there is no reason to believe all benefits would vanish after a child’s second birthday — just diminish gradually. But there is no evidence of medical benefits after two years of age for one simple reason: no one has done studies on it. Since society gets grossed out by four year old children nursing, only a small fringe looks for the benefits of breastfeeding toddlers. Even in this age of celebrating the many benefits and joys of breastfeeding.

Conclusion

Parents should not draw conclusions about the relative benefits of breastfeeding based off this article, as this (young, single, male, non-medical professional) author is not qualified to evaluate the conflicting evidence. And it’s important to note that most prominent critiques of breastfeeding’s benefits come from outside the medical profession. (Depending on your perspective, that could be because they fail to interpret the medical studies correctly, or because only outsiders boldly proclaim what researchers note in the diplomatic language of medical journals.)

There is also obvious common ground for both advocates of breastfeeding and defenders of formula. The strongest advocates of breastfeeding believe it should be a mother’s choice; the most stringent defenders of formula say that breastfeeding can be a wonderful experience for mother and child. Both sides have an interest in making it a real choice by supporting an enforced right for mothers to be able to nurse in the workplace and public, enjoy longer maternity leave, and make a decision based off a clear analysis of breastfeeding’s benefits without the manipulation of formula companies or oversimplifications of the research.

At the same time, the sudden rise of formula use and the equally sudden reversal that occurred with only partial connection to measured medical consensus is a reminder that a skeptic’s eye is always necessary.

This post was written by Alex Mayyasi. Follow him on Twitter here or Google Plus. To get occasional notifications when we write blog posts, sign up for our email list.