With an estimated 3.5 billion fans, soccer is the world’s most popular sport. Stadiums like FC Barcelona’s Camp Nou sometimes house over 100,000 fans and often exceed maximum capacity. Combined with the charged environment, it’s a recipe that can lead to riots and stampedes.

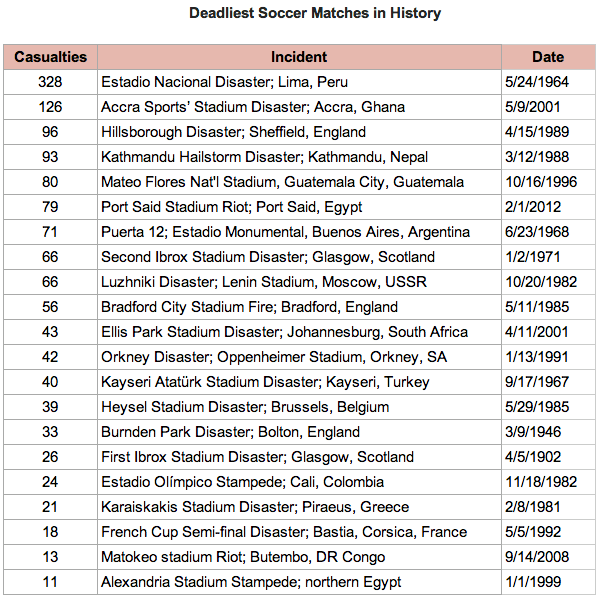

Often, police forces present at the matches aren’t equipped or prepared for these situations; even in the event that they are, a long list of incidents attests to their general inability to control large crowds of soccer fans. Of history’s 35 deadliest sporting disasters, 22 (63%) occurred at soccer matches — easily trumping the second deadliest sport for spectators (racecar driving):

Data via Wikipedia; excludes aviation disasters and indirect incidents (ie. The Soccer War of 1969)

Below, we’ll take a look at the three deadliest ever — The Estadio Nacional Disaster (Peru), The Accra Sports Stadium Disaster (Ghana), and The Hillsborough Disaster (England) — all of which were the result of police mismanagement.

1. The Estadio Nacional Disaster

On May 24, 1964, the national teams of Peru and Argentina were pitted together in the penultimate qualifying round for the Tokyo Olympics’ tournament. The match, hosted by Peru at Estadio Nacional (National Stadium) in Lima, drew a maximum capacity crowd of 53,000 — 5% of the capital’s population at the time.

The game was passionately contested by both teams, and with two minutes of normal time remaining, Argentina led 1-0. Then, miraculously, Peru scored an equalizing goal — but it was disallowed by the referee, Ángel Eduardo Pazos (an Uruguayan who was thought to have been biased toward an Argentine victory). In a span of ten seconds, thousands of Peruvian fans went from unadulterated joy to fury.

The disaster began when one spectator — a bouncer named Bomba — ran onto the field and smacked the referee; when a second fan joined in, he was brutally assaulted by the police with batons and dogs. Jose Salas, a fan who was present at the match, told the BBC that this was the disaster’s catalyst. “Our very own policemen were kicking him and beating him as if he were the enemy,” he recalls. “This is what raised everybody’s anger – including mine.”

As the assault unfolded and frustration over the referee’s call mounted, dozens of fans stormed the pitch, and the crowd began hurling objects at the police and officials below. A riot ensued, and police launched tear gas canisters into the crowd, which prompted tens of thousands of fans to attempt to flee the stadium via its stairwells. When fans reached the bottom of these passageways, they found that the steel gates leading out to the street were locked shut; as they attempted to run back up, police threw more tear gas down into the tunnels, inciting a mass hysteria and causing an enormous crush.

Salas was among those trapped in one of the stairwells, and estimates he spent two hours in a crowd packed so tight that his feet did not touch the floor. Finally, the gates were unhinged by the immense pressure of bodies, and Salas escaped — but others weren’t as lucky.

In the aftermath, 328 people were killed from asphyxiation and/or internal hemorrhaging, though it’s likely the death toll was higher. Allegations later surfaced that the government had downplayed the number of fatalities and covered up the deaths of multiple people killed by police gunfire.

The judge in charge of investigating the events, Benjamin Castaneda, accused the then interior minister of orchestrating the pitch invasion and the brutal police response, in order to incite the crowd to violence – thus providing a pretext for a violent crackdown. The show of strength was intended, he said, to “make the people learn, with blood and tears” the risks they ran if they challenged the authorities. Jose Salazar, a journalist who’s written extensively about the disaster speculates that the police’s actions were calculated to subdue Peruvians’ “leftist” attitude at the time:

“In Peru, people were talking for the first time about social justice. There were a lot of demonstrations, worker movements and communist parties. The left was quite powerful, and there was a permanent clash between the police and the people.”

Many details surrounding the incident are still unclear, and Peru’s Ministry of Interior has never fully attempted to explore them. To this day, the Estadio Nacional Disaster is the worst in the history of association soccer.

2. Accra Sports Stadium Disaster

Almost exactly 37 years later, on May 9, 2001, a nearly identical disaster occurred. Ghana’s two most prominent teams — Accra Hearts and Asante Kotoko — came together for a match at Accra Sports Stadium that would become the deadliest sporting disaster in African history.

Due to the heated nature of the rivalry, extra security had been ordered, and trouble had been anticipated. When the match ended in a 2-1 Accra Hearts victory, the match lived up to its expectations: angry Kotoko fans began ripping plastic chairs out of the ground and hurling them onto the pitch. As with the Estadio Nacional Disaster, police responded by launching tear gas and firing plastic bullets into the crowd — not just at those guilty of hooliganism, but at everyone present.

A massive stampede of 40,000 fans rushed to exit the stadium, resulting in packed corridors; by the time the masses had cleared, 127 lay dead, most from compressive asphyxiation. Abdul Mohammed, a 35-year-old mechanic who was at the game, was trampled and laid out beside those considered dead. He recalls waking up with a sharp breath just before being dragged off to the morgue:

“A lot of people were on top of me that night. Blood was all over as people were crushed to death. I tried to force myself out, but my strength had gone. I didn’t know how I passed out. It was a big miracle for me to have my eyes opened at the mortuary, else I would have been buried alive.”

Incredibly, the Accra Disaster was the last of four soccer-related incidents in Africa in a one-month span. Four weeks prior, on April 11, 2001, 43 people had been killed in South Africa’s Ellis Park Stadium when police fired tear gas and caused a stampede. On April 29, 8 fans were killed at a Democratic Republic of the Congo match, and on May 6, one person passed away after a soccer riot in the Ivory Coast.

3. Hillsborough Disaster

April 15, 1989, will forever be remembered by English football fans as the deadliest match in European history — and an inexperienced police force was largely to blame.

The match — a Football Association semi-final between Liverpool and Nottingham Forest — was highly anticipated. As per custom, a neutral venue was selected (Hillsborough Stadium, in Sheffield, England); opposing fans were segregated, with Liverpool fans placed in the “Leppings Lane” stand. A high volume of Liverpool fans in conjunction with limited entry to Leppings Lane (there were only seven turnstiles) led to severe overcrowding outside the venue. To relieve the crowding, David Duckenfield — Chief Superintendent, and the police officer tasked with overseeing the match — opened an exit gate that led to two already packed enclosures.

Nearly 3,000 eager fans poured in through the gate — nearly double the safe capacity — crushing those already inside the sections; moments after kick-off, a defense barrier snapped, and the crowd rushed forward, while those up front fell to the ground and were trampled. Pressed up against a chain link fence, dozens more were crushed to death before the eyes of policemen, players, and officials on the field. Six minutes into the match, the chaos was so intense that the game was stopped.

As the crowds were gradually reduced, victims were laid out on the pitch, carried on makeshift stretchers constructed out of advertising boards. In the aftermath, 96 were killed by asphyxiation, and 766 others faced grave injuries.

When Duckenfield was questioned, he inaccurately stated that the exit gate had been trampled down by the fans rather than opened by the police themselves. Additionally, he lied about securing prompt medical treatment: only 14 of the 96 victims had been admitted to a hospital (a later report concluded that as many as 41 of these deaths could’ve been avoided with a prompter response).

The Taylor Report, an inquiry into the matter filed in 1990, found that “the main reason for the disaster was the failure of police control.” Subsequently, it was determined that Liverpool fans had not been at fault for the deaths, and that the law enforcement present at the game had fabricated 116 statements relating to the disaster.

The Dangers of Police Mismanagement

A variety of causes have sparked soccer disasters. For instance, the 1988 Kathmandu Stadium Disaster (the fourth largest in history) was provoked by an especially brutal hail storm, which led to a human crush. Another, The Post Said Stadium Riot of 2012, was the result of a dispute between Egyptian fans: armed with knives, swords, clubs, and stones, Al-Masry supporters rushed those in favor of Al-Ahly, killing 79.

But even in these extreme cases, police were blamed for incompetence, unpreparedness, and inappropriate use of force. In Kathmandu, riot police beat fans fleeing the hail; in Egypt, they failed to do anything to stop the open murders, and refused to open the gates for fans attempting to escape. In countless other instances — The Puerta 12 Tragedy, The Orkney Disaster, The USSR’s Luzhniki Disaster — riot police’s actions only served to exacerbate the issues at hand.

In fact, in 18 of soccer history’s 22 disasters with over 10 fatalities, the police forces manning the crowds were found to be at fault to some degree (though the “offending” officers were rarely prosecuted or charged).

The astronomical amount of money spent on security at soccer matches doesn’t seem to alleviate this fact. South Africa, for instance, spent $133 million on security guards for the 2010 World Cup, only to have them all go on strike over unpaid wages in the middle of the tournament; the South African police dealt with the problem by firing a procession of tear gas and rubber bullets at them. Similarly, Brazil invested nearly $900 million on high-tech vehicles and surveillance equipment for the 2014 World Cup, and employed an astonishing 25,000 security officers to control the 75,000 fans attending the final match (that’s one officer to every three fans). It didn’t work out particularly well: one 23-year-old match-goer was killed by authorities for merely smuggling a bottle of Pepsi into the stadium.

Based on past precedent, it seems a boosted police presence at soccer matches does not correlate with safety.

This post was written by Zachary Crockett. Follow him on Twitter here, or Google Plus here.