“Some doctors would say, ‘Clowns don’t belong in hospitals’…well, neither do children.”

~ Michael Christiansen, inventor of “clown care”

![]()

It’s shortly after 2 PM at the Boston Children’s Hospital, and the halls are quiet. Nurses murmur patient updates, a medical cart can be heard faintly rolling down the corridor, and an EKG machine chirps like a forlorn, mechanical bird from room 303. It’s a calm, unexceptional scene in a building laced with sadness: behind each door, a child lies bed-ridden.

Suddenly, the toot of a horn, joined by the jolly pluckings of a ukulele, can be heard echoing in the stairwell. Then, in a flurry of whistles, goofy laughs, and loud, floppy footsteps, two figures enter the ward and make their way to the receptionist’s desk. As the sounds draw nearer, small, bald heads eagerly rise from pillows, and smiles unfold. The clowns have arrived.

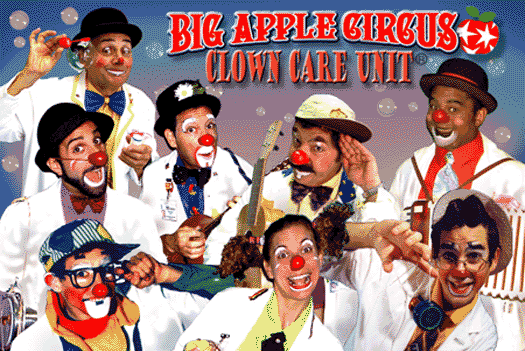

As part of the Big Apple Circus’ ‘Clown Care Unit,’ the two entertainers will make the rounds at the hospital, brightening patients’ day with humor, and giving them an opportunity to reclaim what they rarely get in their lives: control.

For Michael Christiansen, the clown who founded the program, this is the culmination of a decades-long dream to bring joy to lonely, sick children.

Portrait of the Artist as a Young Clown

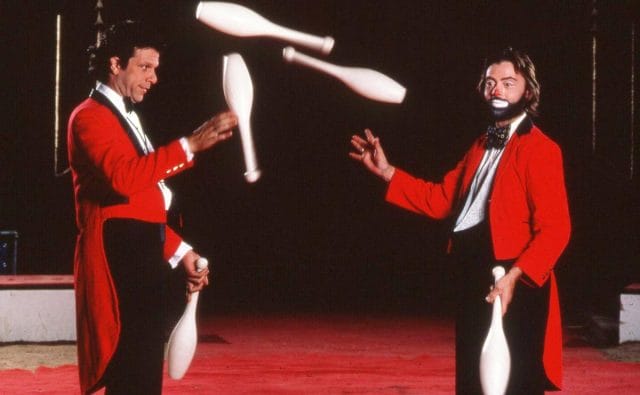

Michael Christiansen (right) and Paul Binder juggling; via Circopedia

Born in Walla Walla, Washington in January of 1947, Michael Christensen endured an “unhappy, dysfunctional” family life throughout much of his youth. He found solace in humor and, in his late teens, enrolled in the University of Washington’s newly-established Professional Actor Training Program.

Graduating in the tumult of the late 1960s, Christensen joined the legendary San Francisco Mime Troupe, a politically-charged, controversial street theatre company, and found himself at the apex of the burgeoning counter-culture movement. Here, he met Paul Binder, an enthusiastic, like-minded juggler looking to start a new project. The duo spent a few months supplementing their $30 per week income — Christensen found work on an apple orchard, and Binder drove a taxi — then, the two met up in London and started what was to be a “great adventure.”

“We juggled for 18 months, from London to Istanbul,” Christensen tells us. “Paris was our base: we got a job at Casino de Paris, a Moulin Rouge-type show, and performed there in front of curtain while they changed the huge set in between scenes.”

After a year and a half on the road, the transient circus lifestyle had exhausted the duo, and they returned to the U.S., where Christensen settled in Seattle on a regional theatre contract, and Binder disappeared into the ether of New York. Then, in 1976, Christensen received a call. “Paul rang and said he’d dreamt of this idea to create a circus. He said, ‘I asked my cat if it was a good idea, and the cat said yes,’” recalls Christensen. “Then Paul asked if I would help him launch it.”

On New Years’ Day, 1976, Christensen arrived in New York and the two began the difficult task of raising $250,000 to make their project, the Big Apple Circus, a reality. By then, both were fairly well-known performers in the clown world: they’d not only toured with the French circus, but had appeared on Sesame Street several times, and had put together a formidable routine.

“We networked, and had these big presentations for investors with open rehearsals,” says Christensen. “One person led to another person, until we were put in touch with Alan Silfka, this venture capitalist and businessman who fell in love with us and the circus, and became our founding chairman.”

In July 1977, inside a little, green, 900-person canvas tent in Battery Park, New York, the Big Apple Circus made its debut. From its onset, the production was a not-for-profit operation — one set on providing affordable entertainment to Americans. But the Big Apple Circus’ most gratifying work was yet to come, and Christensen would be right in the middle of it.

The Birth of ‘Clown Care’’

By early 1985, the Big Apple Circus had grown larger than Christensen had ever imagined: it made multiple television appearances, cameoed in a Hollywood movie, and more than a million people came to see the show each year. With special performances offered for the hearing and vision impaired, as well as autistic children, it was among the most accessible, open-minded circuses in the world.

But behind his toothy, on-stage grin and clown make-up, Christensen harbored a terrible sadness: he’d just lost his older brother, Kenneth, to pancreatic cancer. The performer was “leveled” by his grief, and, as a means of coping, decided he’d completely surrender himself to any charitable request that came his way.

“Right before my brother died,” says Christensen, “he gave me this old doctor’s medical bag, thinking my clown persona might have some use for it.”

Serendipitously, Christensen received a call from a doctor at New York Presbyterian Medical Center. She’d seen him perform a few months earlier, and asked him if he’d be willing to provide a little entertainment at ‘Heart Day,’ an event for children who’d recently had open-heart surgery. After visiting the facility and taking some notes on the patients, Christensen rallied a team of clowns from the Big Apple Circus and put on an impromptu show:

“I headed over to the heart day with two other clowns —‘Grandma’ an ‘Mr. Gordoon’ — and we did what we did best. I put on a white coat and became ‘Dr. Stubs.’ we lampooned, and did all the things medical doctors did — eye tests, hearing tests, and the like — as clowns. There was one little girl who had a heart transplant; we had her do a red nose transplant on one of the doctors. It was 20 minutes of the most fulfilling work I’d ever done.”

Christensen was so taken by the experience — bringing humor and joy to ill children — that he initiated a dialogue with the hospital’s director of pediatrics, and began building the framework for a joint clown-doctor partnership. In short time, he was able to secure a grant from New York’s Altman Foundation, and spent the next five weeks “conceiving the theoretical foundation of hospital clowning.”

Michael Christiansen as ‘Dr. Stubs’; via Circopedia

While others had toyed around with the idea of bringing humor and performance into medical facilities (notably the physician Patch Adams, who was portrayed by Robin Williams in a 1998 film of the same name), no organization had ever been put in place to integrate clowns on a larger scale. Christensen’s vision, inspired by the death of his brother, was simple but poignant: to bring “wonder, awe, and excitement” to terminally ill children in hospitals across the United States.

“I have a tremendous amount of respect for [Patch], but we are very different: he’s a self-proclaimed political activist, whereas I am a self-proclaimed professional idiot…we share the same goal of humanizing and integrating joy into healthcare, but we approach it quite differently.”

As the Big Apple Circus continued to take off in 1986, Christensen launched a new division of the company, the Clown Care Unit: “a group of professional clowns, trained extensively in hospital procedures, circus skills, and improvisation.” Working in teams of two, the clowns would visit pre-approved patients at children’s hospitals and brightened their day with 15 to 20-minute routines. After a wave of press, hundreds of hospitals across the country, each paying for Big Apple’s services through fundraising, were eager to be a part of Christensen’s philosophy:

“The goal was to put the child in charge. Hospitalized children aren’t in charge of anything, so we immediately put them in control of us. They were taking care of us instead of being taken care of; we were there to point out what was right with the kids, not what was wrong with them. We were interested in transcending their diseases and sicknesses, and igniting that wonderful kernel of imagination of awe and wonder inside of them.”

For participating clowns, this was no easy task. Christensen’s performers were required to not only be well-versed in the artistry of performance, but to also be well-steeped in hospital procedures and protocols — universal precautions, hygienic practices, and patient histories included.

The job also came at an immense emotional cost for the clowns. “The clowns had to be supported emotionally,” says Christensen. “A lot of natural feelings came up when doing the work: fantastic ones like joy, wonder, and sense of triumph, but also the more difficult ones like loss, grief, helplessness, fear, and anger.” In the early days, the clowns would have a once-a-week meeting where they could express their feelings with one another; today, they have access to a team of professional psychologists.

Hospital clowns entertain a young patron; via Children’s International

In his years as a ‘clown doctor’, Christensen experienced some of the greatest moments of human connection in his life. He relates one tale:

“I was at a hospital in Seattle, and inside this doorway, there was an Arab woman with her 9-month-old baby. Neither I, nor the other clown, spoke Arabic, but we both spoke baby fluently. So, we looked at baby, and together went “Naaaa-na-na-na-naaa!” The baby just burst into an ear-to-ear grin, and the mother melted. We stood there, playing this silly game with that lovely baby, just bathing ourselves in that baby’s moment of joy and the mother’s gratitude. I wasn’t sure if 1 minute, 5 minutes, 10 minutes had passed: that moment took on another kind of sense of time, where everything around me just faded away.”

Other times, relationships with patients ended in devastation.

In 1990, Christensen befriended Carmelo, a 41-pound 14-year-old with kidney, lung, and heart malfunctions as a result of repeated bouts with pneumonia. Carmelo became so smitten with the clowns, that he decided to be one: after repeated pleas, he was accepted as a member of the Big Apple crew, and began making rounds with Christensen, playfully spraying other patients with a toy squirt gun. On one visit Carmelo looked up at Christiansen with wide eyes and said, “I look just like you, only smaller; does that mean you’re like, my dad?”

Months later, Carmelo’s organs gradually began to fail, and he passed away.

Whether or not clown care provides any merit beyond improved morale in medical settings is a matter of debate, though medical research on the topic has suggested that it does. A 2014 paper in European Journal of Clinical Immunology monitored 91 children who were being entertained by clowns during allergy skin prick tests and found that the clowns’ presence significantly decreased the levels of anxiety and pain perceived by the children. Countless other academic reports have defended clowns as “therapeutic vessels.” Even Thomas Sydenham, the father of clinical medicine, trumpeted the medical healing powers of funny men: “The arrival of a good clown,” he wrote in 1660, “exercises a more beneficial influence upon the health of a town than of twenty asses laden with drugs.”

While Christiansen adamantly believes in the power of humor at clinics, he is not quick to attribute it as a healing agent:

“There are a lot of modes of thought out there about the benefits of humor in healthcare settings: people sometimes call us therapeutic clowns, healing clowns, or therapists,” he says. “But we can’t stand in a hospital doorway looking into a sick child and think about therapy. We can’t think about being psychologists. We can’t think about what positive effects being a professional idiot has on children. We simply have to be open and receptive, with no agenda other than to identify that little spark of wonder and magnify it. When we do that, the room fills with vitality: that alone is our reward.”

Clown Care Goes International

Christiansen’s efforts have come with another reward: since launching his clown care unit in 1986, dozens of other like-minded efforts have popped up all around the world.

“Members who worked with us took the idea to Europe, Germany, Italy, Brazil, Canada,” he says. “It’s gone world-wide now.” A quick comb of the Internet verifies this: this author was able to find more than 60 clown care organizations spread across 35 countries, most all of which cite Christiansen as their influencer.

Though Christiansen retired two years ago from Big Apple’s Clown Care Unit, the fruits of his labor continue to ripen: today, the unit boasts some 75 professional entertainers — magicians, musicians, puppeteers, storytellers, mimes, singers, actors, and acrobats — who collectively visit more than 250,000 hospitalized children each year. From some great, expansive clown haven in the sky, he’d like to imagine his brother is smiling down at everything that has unfolded.

“It all started with that doctor’s bag he gave me,” he smiles. “Who would have ever thought what would come out of it?”

![]()

This post was written by Zachary Crockett. You can follow him on Twitter here.

Our next post examines which college majors are the most expensive for textbooks, and which books resell at the highest loss. To get notified when we post it, join our email list.