“Pie is…the secret of our strength as a nation and the foundation of our industrial supremacy. Pie is the American synonym of prosperity. Pie is the food of the heroic. No pie-eating people can be permanently vanquished.”

— The New York Times, 1902

![]()

In America, we often qualify our patriotism in strange terms.

According to Budweiser, a “true patriot” drinks beer from flag-embossed cans. WWE wrestling would have us believe that the spirit of the United States lies in roided-out biceps, scantily-clad women, and cut-off t-shirts. But above all else — ice cream, baseball, and hot dogs included — we take great pride in being “as American as apple pie.”

A brief search of The New York Times archive (which dates as far back as 1851) yields more than 1,500 results for the phrase “American as apple pie.” According to their journalists, here’s a short-list of things that qualify as such: Civil disobedience, hardcore pornography, corruption, lynching people, poverty and misfortune, political espionage, dirty tricks, antifeminism, President Gerald Ford, gadflies, juicy steak, urban Jews, Social Security, bologna, reproductive choice, marijuana, infidelity, racism, clandestine activities, “human guinea pigs”, censorship, President Bush’s mom, immigrants, addictive products, self-help books, and last but not least, Richard Simmons.

But there’s just one little problem with all this: apple pie really isn’t all that “American.”

Tracing the Origins of Apple Pie

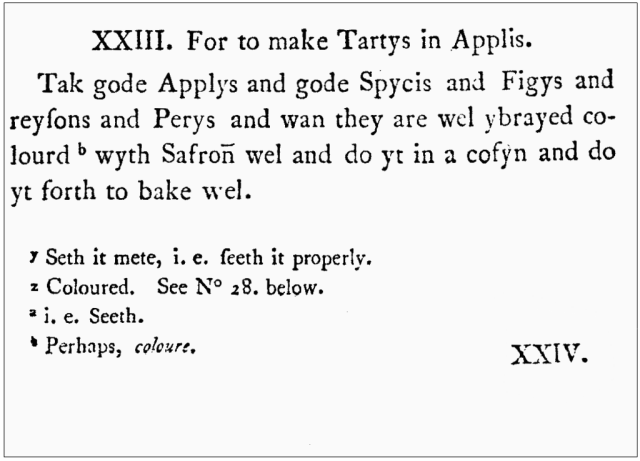

The first known written recipe for apple pie dates back to an English cookbook published in 1381 (original source here).

First things first: the apples we enjoy today are not native to American soil. As far back as 328 BCE, Alexander the Great wrote of modern-day Kazakhstan’s “dwarfed apples”, and brought them back to Macedonia for cultivation. For thousands of years prior to American colonization, apples were integrated in Asian and European cuisine.

By the late 14th century, apple tarts and pies were a common delicacy in England — albeit, they were quite different than modern pies. Due to the scarcity and high cost of sugar (which cost two shillings per pound, or about US$50 per pound in 2014 dollars) in today’s prices), English apple pies did not contain crust, and were instead served in “coffins”, or inedible pans made from natural ingredients.

Apple pies were beloved by the English — so much so, that pastoral writers and poets often alluded to them in romantic soliloquies (“thy breath is like the steame of apple-pyes,” wrote Robert Green in 1590). In the early 1500s, Dutch bakers, who shared this passion, took the concept of the apple pie and pioneered the lattice-style crust we’re used to today; over the course of a century, the pies were ubiquitous throughout France, Italy, and Germany.

It wasn’t until the mid-1600s, through complex sea trade routes, that edible apples made their way to North America. Even then, they came in the form of trees, and required extensive pollination to bear fruit; as such, the fruit didn’t flourish until European honey bees were introduced decades later. Only one type of apple — the malus, or “crabapple” — was native to North America prior to this, and it was incredibly sour and foul-tasting.

Nonetheless, a stream of inaccurate folklore perpetuated the myth that apples were American — mainly stemming from the legend of John Chapman, or “Johnny Appleseed”. While today’s children’s books and fables depict Chapman as an apple-munching, carefree pioneer, every reliable historical source clarifies that he mainly cultivated crabapples for use in hard cider. “Really, what Johnny Appleseed was doing was bringing the gift of alcohol to the frontier,” writes Michael Pollan in The Botany of Desire. “He was our American Dionysus.”

So the question lingers: how in the world did apple pie — a dessert containing a fruit far removed from North America’s landscape — become the reigning symbol of our patriotism?

How Apple Pie Became American

While apple pie was being consumed in Europe in the 14th century, the first instance of its consumption in America wasn’t recorded until 1697, when it was brought over by Swedish, Dutch, and British immigrants. In his book America in So Many Words: Words that have Shaped America, linguist Allen Metcalf elaborates:

“Samuel Sewall, distinguished alumnus of Harvard College and citizen of Boston, went on a picnic expedition to Hog Island on October 1, 1697. There he dined on apple pie. He wrote in his diary, ‘Had first Butter, Honey, Curds and cream. For Dinner, very good Rost Lamb, Turkey, Fowls, Applepy.’ This is the first, but hardly the last, American mention of a dish whose patriotic symbolism is [abundantly] expressed.”

Throughout the 1700s, Pennsylvania Dutch women pioneered methods of preserving apples — through the peeling, coring, and drying of the fruit — and made it possible to prepare apple pie at any time of year. In the vein of many things American, settlers then proceeded to declare the apple pie “uniquely American”, often failing to acknowledge its roots. For instance, in America’s first-known cookbook, American Cookery, published in 1798, multiple recipes for apple pies were included with no indication of their cultural origins.

Several centuries later, the apple pie had become inextricably linked with American lore.

It was a process that began at the turn of the 20th century. Shortly after an English writer suggested that apple pie only be eaten “twice per week” in 1902, a New York Times editor retorted with what must be one of the most passionate defenses of pie ever written:

“[Eating pie twice per week] is utterly insufficient, as anyone who knows the secret of our strength as a nation and the foundation of our industrial supremacy must admit. Pie is the American synonym of prosperity, and its varying contents the calendar of changing seasons. Pie is the food of the heroic. No pie-eating people can be permanently vanquished.”

With that, the seeds of apple pie patriotism were planted.

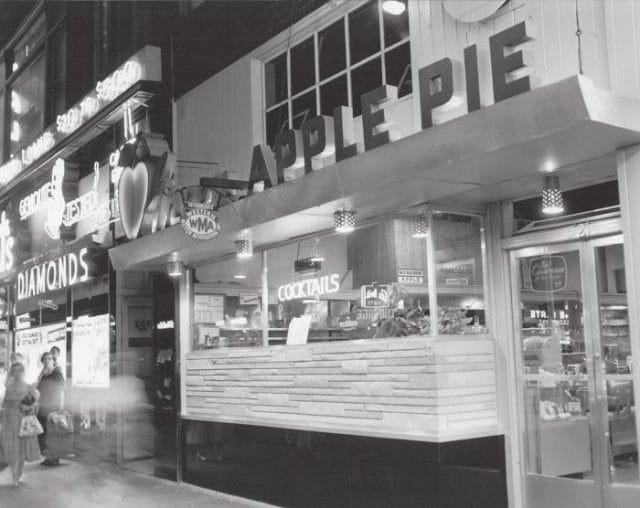

A shop proudly advertising apple pies during World War II (c.1940s)

The primary origins of “as American as apple pie” are difficult to pinpoint, but it was used as early as 1928 to describe the home-making abilities of Lou Henry Hoover (President Herbert Hoover’s wife). The next result we could dig up, a Times article in which the phrase is enlisted to describe lynchings, comes nearly a decade later. It is fair to assert that though the phrase was floating around in the early 20th century, it was seldomly used.

It wasn’t until the 1940s, when the United States entered World War II, that “as American as apple pie” truly took off. When journalists at the time asked soldiers why they were willing to fight in the war, the typical response was “for mom and apple pie.” Even back then, as the phrase emerged, cultural observers were skeptical of it. “The old saying ‘As American as apple pie’ is a bit misleading,” writes a columnist in 1946, “for the chief ingredient of our national dessert is American only by adoption.”

Regardless, news archive search results indicate a tremendous upswing in the use of the saying in the 1960s, and apple pie continued on to establish itself as the reigning symbol of American patriotism.

Can We Call Apple Pie American?

Despite the efforts of Johnny Appleseed, the United States produces only about 6% of the world’s apples today. China, on the other hand, cultivates more than 35 million tons, or about 50%, of the world’s apples. But when it comes to integrating these fruits into pies, it is difficult to argue against America’s pride for the pastry.

According to the American Pie Council, Americans consume $700 million worth of retail pies each year — and that doesn’t include those that are home-baked, or sold by restaurants and independent bakers. Of those who responded to surveys, 19% of Americans — some 36 million people — cited apple is their favorite flavor. That’s a lot of apple pie.

Though we’ve made the case here that apple pie isn’t so American after all, one could argue that just because something originated somewhere else doesn’t mean that it shouldn’t become a source of national pride elsewhere. America took the apple pie to heights it had never seen before — elevated it as a treasured part of its lore and history. And though it wouldn’t be fair to call apple pie “American” without acknowledging its past, the baked good seems to be just at home here as anywhere else in the world.

![]()

This post was written by Zachary Crockett. You can follow him on Twitter here.

To get occasional notifications when we write blog posts, please sign up for our email list.