Photo by Joseph Lee

In 2001, sports psychologists Timothy Cleary and Barry Zimmerman pulled together a sample of about 50 high school basketball players with differing skill levels. There was an “expert” group– varsity players who had made over 70% of their free throws during basketball season. There was a “non-expert” group– varsity players who had made under 55% of their free throws. And there was a “novice “group”– those who hadn’t played organized basketball since 7th grade.

Cleary and Zimmerman had everyone shoot 20 free throws. Whenever a player missed consecutive shots, they asked him a question: “Why do you think you missed those last two shots?”

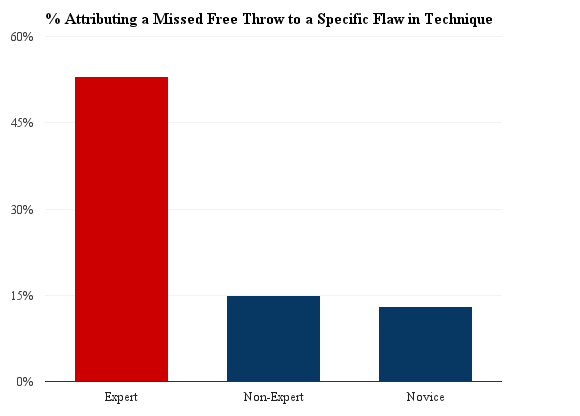

When the psychologists analyzed the responses, they noticed something. The experts were far more likely to have attributed their misses to specific flaws in technique:

Over 50% of experts responded with specifics, like “because my elbow was going to the left” or “didn’t follow through on my shot.” Meanwhile, both non-experts and novices were more likely to respond with generic comments such as “I was thinking too much.” When expert shooters failed, they had specific reasons. For everyone else, bouncing back was more of a mystery. To Cleary and Zimmerman, these findings suggest that experts have much stronger self-correction mechanisms:

“Players taught to attribute their failure to specific processes are more likely to focus on specific processes during subsequent practice sessions. […] Novices and non-experts who have not mastered essential form components of specific sport movements can clearly benefit from instruction regarding attributions for the causes of their failure and self-corrective adjustments when they are not performing well.”

According to this study, experts critique themselves in a way that can help them improve in the future by giving them something to practice. On the other hand, when non-experts fail, they just shrug their shoulders.

To get occasional notifications when we write blog posts, sign up for our email list.