This post is adapted from the blog of Flexport, a Priceonomics customer. Does your company have interesting data or insights? Become a Priceonomics customer.

![]()

In Ancient Rome, shipping was a very big deal.

Sea voyages were a major economic activity—and a risky one. Ships sank, ran afoul of piracy, suffered delays due to weather, or arrived to find that prices were unexpectedly low. This made insuring and financing voyages the high finance of the time. Before there were private equity firms and hedge funds, there was cargo insurance. It was a speculative way for wealthy families and private banks to earn high returns—as long as ships arrived safely in harbor.

Today, however, the shipping industry no longer dominates the way it did in Ancient Greece and Rome or 18th century London. Most people never consider the skyscraper-sized container ships that carry clothes, grain, and other cargo from one port to another.

Nor do most people consider the $30 billion maritime insurance industry that insures that cargo for a few cents on the dollar against the possibility of, say, a giant container of cargo falling overboard in stormy seas—a calamity that befalls an estimated 2,000 to 10,000 containers (much less than 1% of all containers) each year.

But 2,000 years ago, cargo insurance was also essential to the survival of some of the world’s first great cities. Rome’s population was the largest in the Western world until 18th century London. Athens and other Greek cities grew large on the strength of their ports rather than landholdings. Without the Ancient Romans insuring trading ships, those cities would never have received enough food each year to become large urban centers whose accomplishments we still study and admire today.

An Alternative to the Oracle

Maritime insurance is the oldest form of insurance by centuries. But it looked very different when it was sought by sailors crossing the seas that Odysseus had found so perilous. It was much more speculative.

Instead of paying a fee to insure their cargo, merchants funded their voyages with loans that also served as insurance. The loans had very high interest rates, because under the terms of the loan, if the ship sank or the voyage did not succeed, the merchant did not have to repay the loan. This practice, which dates back to at least 1800 BCE and Ancient Babylon, is known as “bottomry”—a reference to the fact that lenders could claim the ship itself if they were not paid back on time.

In Chances Are… Adventures in Probability, Ellen and Michael Kaplan describe bottomry as an amalgam of modern financial concepts:

It is an arrangement that is easy to describe but difficult to characterize: not a pure loan, because the lender accepts part of the risk; not a partnership, because the money to be repaid is specified; not pure insurance, because it does not specifically secure the risk to the merchant’s goods. It is perhaps best considered as a futures contract: the insurer has bought an option on the venture’s final value.

Still, it’s clear that merchants and lenders used bottomry and maritime loans to minimize risk and maximize profit. In Ancient Greece, lenders demanded higher interest rates during stormy seasons. They also charged higher rates to unreliable borrowers like Aischines, a merchant whose reputation led Athens’ maritime lenders to say it was “less risky to ‘sail to the Adriatic’ than to deal with this fellow.”

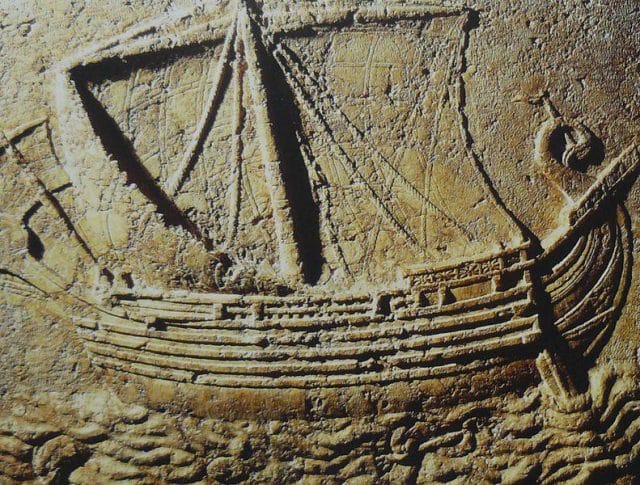

A ship depicted by the Phoenicians, a trading culture on the Mediterranean that interacted with the Greeks and Romans. Source: Elie Plus via Wikipedia

Greek lenders did not jealously guard access to the best deals. Instead it seems that Athenian lenders spread the risk by investing and insuring small amounts in many voyages. Surviving records of maritime loans all show more than one lender per vessel.

Historians believe that Greek merchants and lenders thought of the high interest rates as compensation for taking on the risk of the voyage failing. They also note that Rome copied the practice of bottomry from the Greeks, and a legal text from 500 AD, when the Empire’s capital had moved to Constantinople, explicitly confirms that Romans equated high interest rates with paying for risk. At the time, Roman law capped interest rates at 12%. Yet as James Franklin notes in The Science of Conjecture, the law sanctioned higher interest rates in the case of maritime loans because “the price is for the peril.”

This is why historians consider bottomry and maritime loans to be the earliest form of cargo insurance.

In myths, tragic figures consulted the Oracle at Delphi before embarking on hazardous journeys. But in reality, the Greeks invented insurance so that Poseidon could never completely bankrupt them.

Why the Ancient World Needed Insurance

Many historians used to think that the Greeks and Romans rarely engaged in financial wheeling and dealing.

The chief proponent of this view was Moses Finley, an influential scholar who portrayed wealthy Romans as complacent landowners who spent their wealth on luxuries. Finley believed that advanced markets and the instinct to search out higher returns were modern developments. And he argued that Romans relied on primitive shadows of today’s institutions. He viewed their investments as mostly limited to buying more land, their loans as IOUs between individuals, and their interest in new technologies and creative uses of capital as dulled by the guaranteed returns of owning land and slaves.

But over the past decades, historians and economists have concluded that the Greeks and Romans were pretty excellent capitalists. The ancients had banks that invested in high-stakes real estate with branches spanning the known world. They developed the first health insurance programs. They had proto-corporations called societas that consisted of wealthy Romans pooling money for ventures like providing government services or collecting taxes. They had a single grain market that extended across the Mediterranean.

And, of course, they had thriving markets for maritime loans and cargo insurance.

It’s a good thing a system of lenders and underwriters existed. As historian Wesley E. Thompson wrote in “The Athenian Investor” about bottomry loans, “The system must have worked: the Athenians, after all, did not starve.”

Maritime insurance was crucial in the Ancient World because it allowed cities to grow. Estimates of the population of Ancient Rome put it between 500,000 and 1 million at its peak—making it the largest city in the Western World until 18th century London. Athens probably had a population of around 300,000.

At that size, neither city could survive without regular shipments of grain, and roads were not good enough to transport food at that scale. Indeed, because of the efficiencies of sea transport, it was cheaper to ship grain from Egypt to Rome than to bring it by ox-drawn cart from a mere 100 miles away.

When economic historian Peter Temin calculated how many voyages it would take to feed Rome at its peak—a process better described as guesstimation given the lack of confirmed data—he arrived at 2,000 ships making 4,000 “ship voyages” each year.

From historical accounts, we know that merchants sailed from Egypt, Turkey, and the entire Mediterranean to bring food to Rome’s port of Ostia. (Another several hundred barges took goods by river from Ostia to Rome’s markets.) Historian Kevin Greene describes “Roman agricultural products… being processed by machines, packed in amphorae, shipped great distances in large freighters, and distributed by inland waterways or roads to consumers.”

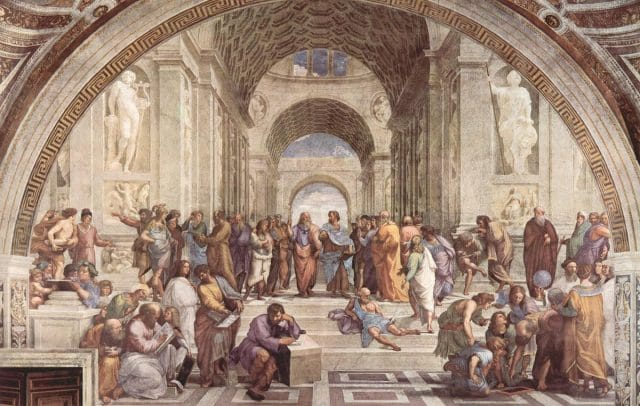

A smaller but equally vital trade fed Athens. Classicist Edward Cohen has noted that “persuasive arguments” have been made that Athens received 600 shiploads of grain each year. Around 400 BC, Xenephon, a wealthy Athenian and student of Socrates, hosted a dinner for traders. He praised them as “benefactors of the city”, recognizing, as maritime specialist Lionel Casson writes, “on which side Athens’ bread was buttered.”

“[O]r rather,” Casson adds, “that without the traders and shipowners there would be scant bread to butter.”

Such a large trading system required a financial ecosystem to fund and insure each voyage. Perhaps the wealthiest citizens of Rome and Athens could have launched voyages themselves. But the wealthy derided merchants and business ventures; like the upper-class characters in Downton Abbey, they saw such work as beneath their station.

Instead wealthy Romans and Athenians preferred to prosper from trade indirectly by fronting and insuring traders, who tended to be foreign and less wealthy. In any case, the fact that lenders provided lots of bottomry loans shows they understood that it was less risky and more profitable to act like financial intermediaries than business operators.

A healthy amount of scholarship seems to agree on the importance of bottomry loans to the shipping industry’s—and ancient cities’—existence. It’s not a hard conclusion to draw, given that even in Ancient Athens, every voyage seems to have had multiple bottomry loans.

The importance of funding and insurance was recognized at the time, too, as in this statement made to a jury in 4th century Athens:

The resources required for trade are provided by lenders: without lenders, not a ship, not a ship-owner, not a traveler could put to sea.

In both AD Athens and Rome, each voyage was a feat of financial engineering, with multiple financial interests at play. Like today, different, lenders, insurers, and merchants were responsible for the ship and different batches of cargo.

Maritime loans were so common that Romans even had a boilerplate, standard contract that lenders sloppily copied for each voyage. Lenders probably sounded like modern contract lawyers: “… repaid with interest, yada yada yada, sign here.”

How Dangerous Were Sea Voyages?

Historians don’t have enough data to confidently estimate how often ships sank in Ancient Greece and Rome.

What we do have are records of shipwrecks—both from written accounts and finds at the bottom of the Mediterranean and Aegean Seas—and the knowledge that losses were common enough that lenders demanded merchants repay them 20 to 30 cents on the dollar (compared to the 12% maximum interest rates on regular loans in Rome’s later period).

Yet those accounts and wrecks come from a Greco-Roman period that lasted a thousand years. In practice, losing ships at sea may have been rare, calamitous events. Edward Cohen makes this point in Athenian Economy and Society; he particularly draws on a 4th century AD account of the public reaction to a freighter sinking, which seemed “akin to the crash of an aircraft at the present time.”

Catastrophic results would have been even more rare at the height of Rome’s power. To boost trade in the early empire, Emperor Claudius acted as a government insurer by covering merchants against losses from storms at no cost. The Romans also, Peter Temin notes, “put considerable effort into unifying the Mediterranean and clearing out pirates that impeded peaceful shipping”—the equivalent of the United States policing global shipping lanes today.

Photo credit: The Parthenon Athens by Steve Swayne

Shipwrecks aside, merchants and their financial backers worried as much if not more about everyday concerns. They worried about being paid in counterfeit currency; about captains pretending that their ship sank to avoid repaying bottomry loans; and about shippers stealing cargo or lying about prices. To manage this, lenders relied on a system of inspections, information sharing, and receipts designed to allow the insurers and financiers to detect and avoid fraud.

It’s tempting to view early traders as bold men who crossed treacherous seas to fill their holds in faraway lands. But captains rarely owned their own ships, and even merchants and captains who had the money preferred to finance their vessel, the voyage, and the insurance on each from maritime lenders who spread the risk. The picture historians have sketched out of ship captains is less Han Solo and more middle management.

***

Surgeons can only cut into patients thanks to hospitals’ liability insurance, which covers the costs of any mistakes. Journalists can engage in investigative journalism because newspapers and magazines purchase libel insurance.

Actors like Tom Cruise brag about performing their own stunts, but the studio’s insurance agent must okay each one.

Even the U.S. military purchases private insurance that pays out if its foreign bases are attacked during peacetime.

Historians do not single out bottomry loans and cargo insurance as the key to the success of Ancient Greece and Rome. Maritime finance is only one factor among many that allowed them to thrive.

Yet it’s clear that Ancient Rome—a city and empire that we associate with gladiators and civil wars, whose founding myth involves twin princes raised by a she-wolf—would not have become a wonder of the ancient world if it weren’t for the existence of an insurance industry that made trade boring, profitable, and dependable.

Our next post profiles Russ Roberts, a man whose quest to get people to give a shit about economics involved equal parts Ke$ha and Milton Friedman. To get notified when we post it → join our email list.

![]()

Note: If you’re a company that wants to work with Priceonomics to turn your data into great stories, learn more about the Priceonomics Data Studio.