![]()

On February 17, 2014, a 24-year-old college student named Charles Clarke checked a bag at Cincinnati/Northern Kentucky International Airport and parked himself in a chair near the boarding gate. Having just visited relatives, he was in high spirits, and eager to return to his home in Florida.

But Clarke’s day took an unexpected turn.

Two uniformed men — an airport police detective and a local Drug Enforcement Administration officer — approached by Clarke and corralled him into a fluorescent backroom. His checked bag sat on a table. One of the men turned to him and grunted, “This smells like marijuana.” An extensive search ensued, which yielded no trace of drugs in Clarke’s luggage. But buried between t-shirts, in the young man’s bag, the officers discovered something of greater interest: $11,000 in cash.

The cash, earned through five years of hard work at fast-food restaurants and retail outlets, represented Clarke’s life savings — money he intended to use for tuition fees. But the officers didn’t buy his story. Based solely on the fact that his bag “smelled like weed,” they claimed that the $11,000 was related to drug trafficking and seized it.

***

Under the umbrella of “civil forfeiture,” officers of the law confiscate millions of dollars in cash from thousands of individuals like Charles Clarke every year. In doing so, they need no proof that the money is obtained through illegal means. They do not need to file a criminal charge. The law flips the American justice system upside down: the burden of proving innocence is on the “suspect” — and if he or she can’t do that, the property is fair game for officers to take.

Using cash that is unjustly seized from Americans, police departments across the nation buy firearms, SWAT gear, flat-screen TVs, and a slew of other goods they deem to be “essential” to operation.

But how exactly is this legal, and why is such a crazy procedure permitted in a country that prides itself on its civil liberties?

A Brief History of (Legally) Stealing Other People’s Stuff

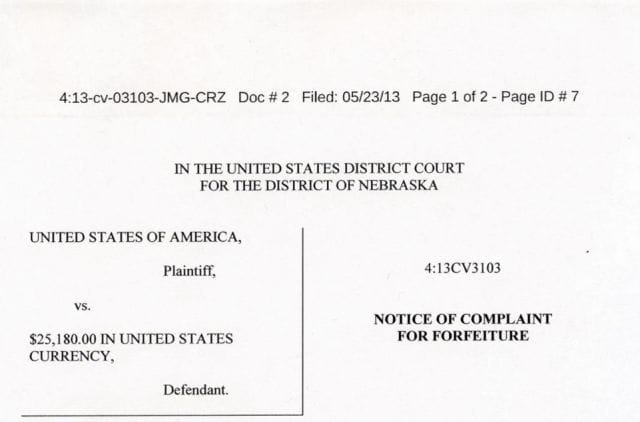

In the United States, the government uses two methods to seize cash or other property. The first, criminal forfeiture, requires that a person be convicted of a crime before his/her property is taken. The second, civil forfeiture, requires neither a conviction nor any proof of wrongdoing. Here, action is taken against a specific piece of property rather than a person, leading to interesting case names like United States v. $124,700 in U.S. Currency, or United States v. 64,695 Pounds of Shark Fins.

The origins of civil forfeiture are often traced back to the British Navigation Acts, a series of maritime laws created in the mid-17th century. To distinguish between trading vessels, it mandated that all ships importing or exporting goods should bear the British flag; any ship that did not do so — regardless of whether or not it broke the law — could be immediately seized.

Settlers in the American colonies saw such forfeiture laws as “unreasonable searches and seizures which deprived persons of life, liberty, or property, without due process.” Nonetheless, Congress adopted its own version of civil forfeiture, allowing government officials to seize the property of anyone who failed to pay his or her taxes. Over the next few centuries, the government only sporadically utilized civil forfeiture — though various derivations of these laws allowed authorities to seize property without a criminal conviction.

While the police only occasionally took advantage of civil forfeiture in the early 20th century, it truly exploded in popularity in the 1980s, with the rise of the War on Drugs. In 1984, President Reagan enacted the Comprehensive Crime Control Act, which enhanced the ability of police officers to seize cash from anyone and everyone suspected of a drug crime. The goal was to systematically dismantle the drug world by seizing cash.

In the zeal of this anti-drug atmosphere, the low burden of proof required of civil forfeiture seizures was seen as an asset.

The War on Drugs can be credited with the rise in use of civil forfeiture laws; Via UDPS

Aside from its abuse of civil liberties, civil forfeiture posed a major conflict of interest: the police got to keep whatever assets they seized. This gave them tremendous incentive to, in the words of one cop, “up the seizure game.” A 1993 Los Angeles Times article harps on some of these abuses:

“A small-town Southern sheriff seized a Rolls-Royce from a drug dealer and uses it as his personal car. Local police in Little Compton, R.I., netted $3.8 million in a drug bust and outfitted their cars with $1,700 video cameras and heat detection devices for a police force of seven. The owner of a sailboat lost the craft after a crew member was caught with a small amount of marijuana.”

Between 1985 and 1993, authorities confiscated some $3 billion worth of cash, cars, boats, jets, and real estate under civil forfeiture laws. In the vast majority of these cases, no evidence of wrongdoing was ever required: police officers used their own judgement in seizing property.

The Reagan administration championed the efforts as an effective crime deterrent. As one White House attorney smugly told the press in 1989: “It’s now possible for a drug dealer to serve time in a forfeiture-financed prison after being arrested by agents driving a forfeiture-provided automobile while working in a forfeiture-funded sting operation.”

But since only a presumption of guilt was necessary, it was not unusual for innocent people — often minorities — to be “legally robbed.” In one case, in 1989, authorities broke into a computer retailer’s safe and took $120,000 in cash. A few months later, a motorcycle shop owner had his Harley-Davidson possessed. Neither man was ever charged with a crime; all the police needed was a “hunch” that they’d acquired these items through illicit means. There was no burden of proof.

“After this ordeal,” Rey Sotelo, the bike shop owner, later told the press, “I believe no one is safe in this country.”

Manipulation of the Law

A civil forfeiture case filed in Nebraska

Today, Sotelo’s fear is more prevalent than ever. While civil forfeiture laws were originally intended to take down multimillionaire drug kingpins, they are increasingly manipulated by — in the words of one Florida police chief — “street cops [looking] to take a few thousand dollars from a driver by the side of the road.”

In a 2014 investigation, The Washington Post identified 61,998 cash seizures made by federal, state, and local authorities on highways over the past decade, totalling in excess of $2.5 billion. The vast majority of the seizures were of relatively small amounts (50% were under $8,800), and due to the high costs of legal counsel, only 1 in 6 cases were challenged. Upon analyzing 400 of these cases more closely, The Post found that those pulled over were predominantly Black, Hispanic, or members of another minority group.

As The Post writes, a “thriving subculture of road officers…now competes to see who can seize the most cash and contraband.” Some officers are so good at sniffing out cash that they make a living as consultants, traveling to different agencies and “coaching” them on the best approaches to utilizing civil forfeiture. One of these men, Joe David, who runs a “stop-and-seizure” firm called Desert Snow, single-handedly brought in $427 million over a five-year period — 25% of which his firm was permitted to keep. Eddie Ingram, an Alabama-based deputy, purports to have brought in $11 million over a similar span.

“All of our home towns are sitting on a tax-liberating gold mine,” writes Illinois Deputy Ron Hain, in a self-published book on cash seizure training. “[We must turn] our police forces into present-day Robin Hoods.”

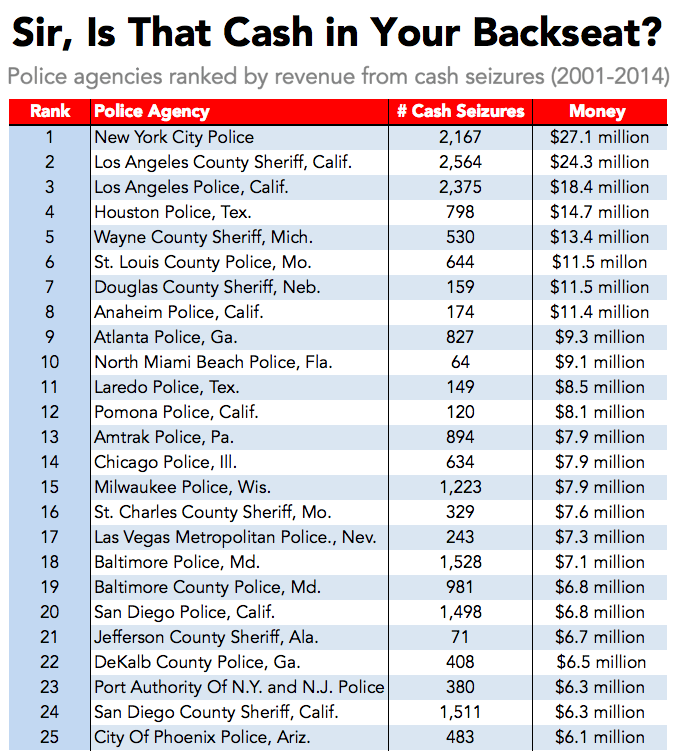

Utilizing the tactics of these self-proclaimed seizure “experts”, certain local police agencies have raked in millions. Below, we’ve delineated the 25 highest-grossing jurisdictions.

Priceonomics; Data via WP (using Department of Justice databases)

Very often, innocent people who just happen to be carrying cash become ensnarled in seizure stops. The Post elaborated on several such instances:

“A 55-year-old Chinese American restaurateur from Georgia was pulled over for minor speeding on Interstate 10 in Alabama and detained for nearly two hours. He was carrying $75,000 raised from relatives to buy a Chinese restaurant in Lake Charles, La. He got back his money 10 months later but only after spending thousands of dollars on a lawyer and losing out on the restaurant deal…

A 40-year-old Hispanic carpenter from New Jersey was stopped on Interstate 95 in Virginia for having tinted windows. Police said he appeared nervous and consented to a search. They took $18,000 that he said was meant to buy a used car…

A 35-year-old African American owner of a small barbecue restaurant in Staunton, Va., was stunned when police took $17,550 from him during a stop in 2012 for a minor traffic infraction on Interstate 66 in Fairfax. He eventually got his money back but lost his business because he didn’t have the cash to pay his overhead.”

Unfortunately, authorities don’t just use civil forfeiture on traffic stops. Until recently, the IRS and Department of Justice also seized property due to violations of an arcane “structuring” law. Federal law requires that individuals report bank transactions over $10,000; if large amounts less than that are deposited in separate chunks, the government assumes the account holder is trying to intentionally evade the law.

Terry Dehko, the owner of a small supermarket in Fraser, Michigan, learned this the hard way. After making several consecutive deposits between $5-8,000 in cash, the government “cleared out” his bank account — more than $35,000 — without offering any warning or explanation.

Jeffrey, Richard, and Mitch Hirsch, three brothers who co-owned a candy distributing business in Long Island, New York, met a similar fate. A series of cash deposits (all under $10,000) drew the suspicion of authorities, who then used civil forfeiture law to seize their $446,000 account.

Police occasionally put “seized by police” decals on possessed cars, then drive them around town to remind everyone of their civil forfeiture powers; via The Province of British Columbia (Flickr)

After attracting a scourge of negative attention (including a 16-minute John Oliver segment), the federal government finally cracked down on civil forfeiture laws.

Early last year, Attorney General Eric Holder, on behalf of the Department of Justice, announced that state and local police departments could no longer take advantage of federal civil forfeiture statutes. (Previously, under an “Equitable Sharing” law, states had been permitted to involve federal agents in order to take advantage of federal law and seize property; then, profits would be split between the U.S. government and the state/seizing municipalities.)

“Asset forfeiture remains a critical law enforcement tool when used appropriately — providing unique means to go after criminal and even terrorist organizations,” Holder said in a statement. “This new policy will ensure that these authorities can continue to be used to take the profit out of crime and return assets to victims, while safeguarding civil liberties.”

Yet, nearly every state has its own civil forfeiture laws — and the Department of Justice’s actions have done nothing to curtail their use. While local and state governments can no longer seize property when working alone, they are still permitted to work through a federal task force, or simply claim a “public safety exemption.”

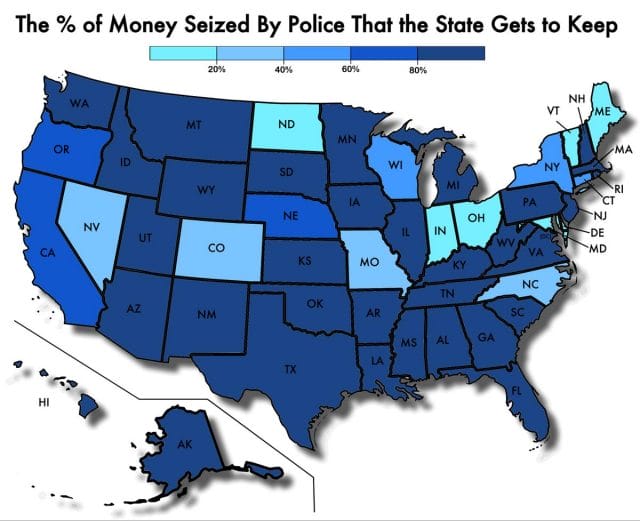

For local and state police departments, civil forfeiture continues to be a big business. According to the Institute for Justice, the laws in most states allow police to keep 80% or more of what they seize — sometimes as much as 100%. For many departments, civil forfeiture makes up a considerable portion of annual revenue.

But what exactly do these agencies do with seized assets?

Who Gets the Money, and What Is It Used For?

“Paul” (name withheld), an ex-police officer whom we contacted, tells us that during his 17-year tenure as a Deputy in Arkansas, his department received “about half a million per year” in seized goods. He elaborates on how this money was used:

“To my understanding, it was set aside to buy things the department needed: new patrol cars — those things aren’t cheap — new monitors, riot gear. You know, stuff we needed but didn’t necessarily have a budget for. So, when this money comes in, it’s considered extra, and we treat ourselves to the basic necessities.”

According to a 2014 investigation, some police departments have quite a wide-ranging definition of “necessities”: officers in Maryland bought a $1 million mobile command center. The Los Angeles PD treated themselves to a top-of-the-line, $5 million helicopter. A small outfit in Douglasville, Georgia (a town with a population of 32,000) purchased a $227,000 armored personnel carrier fit for World War III. Departments also rack up millions in smaller purchases, like $637 coffee makers (Amarillo, Texas), or $2,400 flat screen TVs. One Ohio agency spent $225 on a clown named Sparkles. “The money I spent on Sparkles the Clown is a very, very minute portion of the forfeited money that I spend in fighting the war on drugs,” the buying officer told The Post.

All of this was paid for with money seized from Americans — the vast majority of whom were never charged with any crime.

In instances where a department seizes an item rather than cash, it has two options: “They can either liquidate it or convert it to public use [read: use in the police force],” retired Nevada officer Tim Dees tells us.

“We seized a really, really nice boat,” he tells us. “The sheriff re-painted it, then used it out on Pyramid Lake [40 miles northeast of Reno, Nevada]. If you can put an asset to a legitimate use, that’s fair game.”

For liquidated items, most departments are not permitted to spend the proceeds on “personnel costs” (overtime pay, hiring new officers, etc). “Usually, it’s hardware,” says Dees. “Vehicles, guns, weapons — not so much practical things, as things the high-ranking types buy to pretend they’re in charge.”

A traffic stop in New York; Via Dwightsghost (Flickr)

Beyond the troubling effects civil forfeiture has on innocent people, the law is inherently problematic: since the profits of these seizures are kicked back to the departments overseeing them, they have an incentive to ramp up their practices — often without professional discretion.

One ex-officer explains it to us this way:

“Command staff in local agencies are tasked with finding as much money as they can to work with, and making what they find stretch as far as they can. Local (municipal) agencies, in my experience, are funded with sales tax revenue within the city in question. In a tough economy, it’s probably the case that sales are down and crime is up, thus creating a financial pinch when resources are needed that much more. So if there is a means by which decision makers can legally procure additional assets in order to shore up budget shortfalls, they’re assuredly going to do their homework and make it happen.”

The problem is that very often, the focus of these departments is more on obtaining money than upholding justice. Civil forfeiture — which allows police to seize cash and other property without pressing any criminal charge — makes this all too easy for them to accomplish.

Charles Clarke has yet to recoup his $11,000 life savings; via Institute for Justice

Today, Charles Clarke continues the fight to get his $11,000 back. Nearly two years after his college savings were seized by the authorities at the airport, he has yet to re-coup a penny. The ramifications of his financial loss have been wide-reaching: He’s moved back in with his mother. He’s had to reach out to family members for monetary support. Without cash to pay upfront, he’s resorted to student loans, putting him thousands of dollars in debt.

Currently, the Institute for Justice, a law firm that seeks to “protect simple American freedoms,” is assisting him. But once civil forfeiture money is seized, it can be incredibly challenging to get back — even with good legal counsel. Clarke, like the thousands of others in his predicament, faces an uphill battle.

“It’s ridiculous,” he said earlier this year. “We’re treating innocent people like criminals.”

![]()

Our next post investigates whether cigarette taxes are unfair to the poor. To get notified when we post it → join our email list.

![]()

This post was written by Zachary Crockett. You can follow him on Twitter at @zzcrockett