Newspapers and magazines are in trouble. We think they will mostly die, because we think we know what will replace them, and it is too far from their current model for them to reach it in time.

And yet people still need at least some of what they do.

– Paul Graham, Request for Startups 1: The Future of Journalism

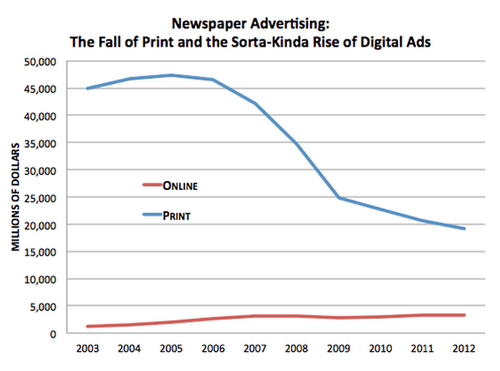

The journalism industry seems to be in trouble. Newspaper revenue has shrunk from $57.4 billion in 2003 to $38.6 billion in 2012. All of their traditional sources of revenue are falling. Magazine circulation is down sharply. Publishers have laid off their staff en masse or shut down entirely. It is harder than ever to make a living as a journalist.

Let’s rehash what has already been said ad nauseum: the Internet killed the business model that previously funded journalism. Newspapers, for example, used to collect subscription fees to deliver a physical product. They also earned good advertising revenues because companies had few options for advertising their products. This was especially true for local advertisers posting in the classified section of newspapers. With the Internet, however, distribution became free, places to advertise became plentiful, and “local” became an abstraction.

If the incumbents of journalism are dying, what will replace them? Or, more precisely, what new business model for journalism will emerge if the old one is dead?

Online advertising has not, thus far, proven to be the savior of online journalism. Since the supply of websites that businesses can advertise on is so plentiful, the revenue per advertising impression is tiny. Online ads are simply not bringing in enough revenue to sustain news outlets. Print advertising dollars are being replaced by digital advertising cents:

Because these online ads generate so little money per pageview, you need a lot of pageviews to run a business. This sets up up strong incentives to grow pageviews through annoying slide shows, misleading headlines, and recycling other people’s original content. Publishers are competing hard to get the most pageviews, and so far, that hasn’t proven to be a good way to fund original content and reporting.

For the last two decades, the conversation has been about “how do you save newspapers.” Now the conversation is starting to center around what replaces newspapers to save journalism. Investor Paul Graham has challenged startups to invent a new business model for journalists that supports great writing rather than link baiting and slideshows:

What would a content site look like if you started from how to make money—as print media once did—instead of taking a particular form of journalism as a given and treating how to make money from it as an afterthought?

In this post, we look at some of the experiments taking place today to fund high quality content. We hope it can be a starting point for people to discuss how they would save journalism. That’s probably what’s needed to save journalism, brainstorming new ideas and then trying them.

In that spirit, this post ends with an experiment that you can participate in. The proceeds of the experiment will go to charity, but it’s a small test of whether people are willing to pay for content.

So, what do people talk about when they talk about a business model for journalism?

Paywall

The most commonly discussed business model to save journalism is a subscription paywall. Subscribers pay a monthly fee to publishers for access to their content. The upside of this approach is that readers directly fund the journalism. Whereas advertisers don’t really care about funding high quality investigative reporting on inner-city schools, subscribers might.

The most commonly discussed business model to save journalism is a subscription paywall. Subscribers pay a monthly fee to publishers for access to their content. The upside of this approach is that readers directly fund the journalism. Whereas advertisers don’t really care about funding high quality investigative reporting on inner-city schools, subscribers might.

Paywalls that keep non-subscribers from accessing content can be rigid (you must pay to see anything) or porous (you can see a lot, but not all, of the content for free). There have been a few flagship examples of paywalls working to some degree. The New York Times and Wall Street Journal have paywalls, but they are the leading newspapers in the world. Even if paywalls work for them, would it work for the 3rd best newspaper? What about the 10th best paper? What about a one person blog? So far the evidence strongly suggest no.

Take the example of Newsday, a Long Island newspaper that was purchased in 2009 for $650 million. Under the new ownership, the website was put under a paywall. After 3 months, Newsday only managed to get 35 subscribers for its online content. Redesigning the website for subscriptions cost $4 million and only generated $9,000 in revenue. Ouch.

These paywalls lead to some perverse consumer behavior. People show boundless creativity to get around paywalls. Even readers that can easily afford a New York Times subscription confess to jumping the paywall by opening new browsers, Googling the articles, and borrowing friends’ passwords.

By limiting distribution, paywalls also hinder outlets’ ability to find new readers. Felix Salmon of Reuters comments:

But there’s another consideration, too: the more formidable the paywall, the more money you might generate in the short term, but the less likely it is that new readers are going to discover your content and want to subscribe to you in the future.

Several startups have recently used subscriptions to fund journalism with some success. Marco Arment’s The Magazine, a fortnightly iOS magazine, costs $2 a month. Andrew Sullivan’s The Dish costs about the same amount. Sullivan’s experiment has generated over $600,000 in revenue and he’s very transparent with his readers about the financial performance of his site.

An interesting aspect of both The Magazine and The Dish is that neither seems to take something away from the reader (unlike, say, The Wall Street Journal’s paywall). Most readers of the The Dish will never hit the paywall, but many of them decide to subscribe on a voluntary basis. 29% of the the people that subscribe to The Dish have never even logged in to claim their subscriber benefits. Moreover, The Magazine never existed without a paywall, so readers never felt like content was taken away form them.

Micropayments

Micropayments have been bandied about as a means to save journalism since the advent of the web. The premise is that a good piece of writing has some economic value, but it might only be about a penny or a dime per view. Walter Isaacson summarizes it well:

The key for attracting online revenue, I think, is coming up with an iTunes-easy, quick micropayment method. We need something like digital coins or an E-Z Pass digital wallet – a one-click system that will permit impulse purchases of a newspaper, magazine, article, blog, application, or video for a penny, nickel, dime, or whatever the creator chooses to charge.

Clay Shirky presents the other side of the argument, contending that micropayments won’t work:

This strategy doesn’t work, because the act of buying anything, even if the price is very small, creates what Nick Szabo calls mental transaction costs, the energy required to decide whether something is worth buying or not, regardless of price.

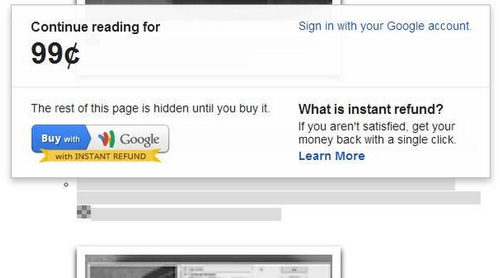

Google and Paypal introduced some micropayment offerings for publishers, but Shirky’s argument is that no one is going to stop their flow of reading articles to pay for one by Google Wallet. The friction is too high.

So, is the key to saving content building a micropayments system that’s completely frictionless? Maybe, but Shirky’s argument goes further. Micropayments don’t solve any problems for users. They hypothetically solve problems for publishers, which is why newspapers and publishers keep talking about them. But readers are not clamoring to pay nickels and dimes for articles. Moreover, for most articles, good free substitutes are available online. So the article would have to be extraordinarily unique for a user to cough up even a penny.

To our knowledge, no journalistic organization or content startup has funded its writing through micropayments. Even Google’s micropayment service seems to be shuttered. Despite many attempted technology solutions to facilitate micropayments, no publishers seems to have found a way to make it work.

Under what circumstances would micropayments work? The friction of purchasing content would need to be near zero – as easy and unnoticeable as purchasing electricity. The content would need to be unique and not easily “substitutable.” And finally, to borrow from the lesson of Andrew Sullivan’s website, it might help if users felt like they were volunteering the payment instead of being scolded into it.

Subsidy Model 2.0: Content as Lead Generation for More Profitable Things

The expense of printing created an environment where Wal-Mart was willing to subsidize the Baghdad bureau. This wasn’t because of any deep link between advertising and reporting, nor was it about any real desire on the part of Wal-Mart to have their marketing budget go to international correspondents. It was just an accident. Advertisers had little choice other than to have their money used that way, since they didn’t really have any other vehicle for display ads.

– Clay Shirky, Newspapers and Thinking the Unthinkable

Some of the most successful blogs make their money in ways not directly related to their writing. For example, TechCrunch and All Things Digital put on very successful (and profitable) tech conferences. Some personal blogs generate leads for a profitable consulting business or training course.

This is a profitable way to fund original content, but the writing is still subsidized by something else. The writing is what builds the brand that allows the publisher to cash in on other revenue sources. So it’s a symbiotic relationship, but still a relationship where reporting is being subsidized.

Other content companies use the web to generate leads to sell their content in other forms. The Oatmeal, a most excellent webcomic, has a free website. You can, however, purchase comics on prints and t-shirts or in print books (that also have original comics). The vast majority of users read the digital comics for free and some of them purchase that content in other forms. This is a common business model among people debating the economics of writing content for a living. They publish free articles online as lead generation for books.

Pay What You Want

In 2007, Radiohead released their album In Rainbows online and let fans choose what to pay for the album. It was a solid success, but this was freakin’ Radiohead. Can it work elsewhere? After all, Radiohead hasn’t even used its pioneering model on subsequent albums. However, we are seeing this this model of fans paying what they want applied to other forms of content.

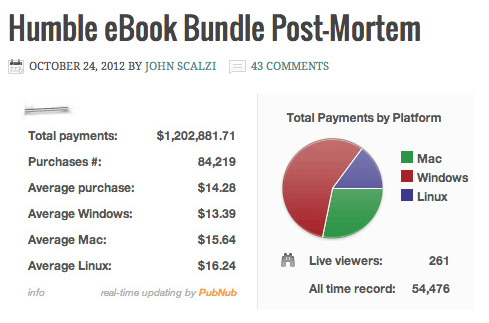

Humble Bundle, for example, let’s fans choose to pay what they want for indie video games. But the gamers also decide what portion of the purchase price should go to charity and what portion to Humble Bundle as a tip. It’s a purely voluntary business model. Bundles of video games frequently generate millions of dollars in sales. The company even did a bundle of e-books that generated $1.2 million in voluntary sales.

Would this work if video game giant Electronic Arts put on a similar “pay what you want” promotion with their games? There is some evidence that pay what you want models only work with some charitable component or cause like supporting independent developers.

In 2010 Berkeley researchers performed an experiment selling souvenir photos to people after they rode a roller coaster. They tried 4 different pricing schemes. The first was a flat fee of $12.95 for the photo. The second was a flat fee of $12.95 for the photo, but half the money went to charity. The third was to pay what you want for the photo. The final scheme was to pay what you want for the photo, with half the money going to charity.

Allowing people to name their own price was a complete disaster. Everyone lowballed the researchers. But when customers paid what they wanted and half the money went to charity, the researchers raked in money. It generated 3X more revenue per rider than any other option. Adding a charity component to the flat fee had basically no effect on whether someone would buy it.

When people can pay what they want, this experiments indicates it helps if there is a worthy cause attached to it. In that case, it works well. Otherwise, customers will choose to pay almost nothing.

“Pay what you want” has also been reincarnated on Kickstarter. Yes, tangibly you get prizes for donating. But there is also the feeling of connecting with the campaign creator and being part of a cause. Felix Salmon of Reuters comments on how a pay what you want model responds to netizens aversion to paying for content:

On the internet, people prefer carrots to sticks. That’s one of the lessons of Kickstarter, too. To put it in Palmer’s [a prominent Kickstarter campaigner] terms: if you want to give money, you’re likely to give more, and to give more happily, than if you feel that you’re being forced to spend money.

The “pay what you want” business model is purely voluntary. The amount a user can give is uncapped. Most people will give nothing or very little, but passionate fans can give a lot if they want. Even successful paywalls like Andrew Sullivan’s at The Dish can be viewed through the “use carrots not sticks” lens. Most of his supporters aren’t hitting paywalls and many of the suscribers never even log in. Are they really buying access to content or are they supporting a cause and journalist they care about?

How could you use carrots and not sticks to fund content? Let’s do a quick experiment.

An Experiment: Decide what we write about on our blog and support charity

We get a lot of emails at Priceonomics from readers with suggestions about topics they’d like for us to write about on the blog. We love getting the suggestions, but we never have enough time to properly research them.

So, here’s a test: if you make a donation to charity, you can dictate what we write about next.

Send us any amount of money (which we’ll donate to charity) and you can vote to decide on the topic of our next blog post. If there has ever been a topic that you thought, “I wish someone would spend 50 hours researching this and then write a story or report about it,” now is your chance.

Send us a dime, a dollar, a thousand dollars… whatever you want by Paypal or Bitcoin. If you donate more money, you’ll get slightly more votes on choosing the next blog post. So be generous! We’ll donate all of the proceeds to charity (EFF, Pro Publica & Watsi). Apologies in advance that both Paypal and Bitcoin are not easy to use.

Click the above button or use this link to donate by Paypal

Donate by Bitcoin: 1AxzBwU2FygXmW3WNHZHkGdFFTVHX3P68u

Send us your blog post suggestions on Paypal (or by email) and then we’ll aggregate the suggestions and follow up with you by email to vote and choose the winner of the next blog post. We’ll update the results below.

Number of Donors: 15

Total Amount Raised for Charity: $180.22

Average Amount: $12.01

Most Generous Donation: $50

Conclusion

“If the old model is broken, what will work in its place?” The answer is: Nothing will work, but everything might. Now is the time for experiments, lots and lots of experiments…

– Clay Shirky, Newspapers and Thinking the Unthinkable

Over the last two decades, the Internet thoroughly crushed newspapers and magazines. These organizations might survive, or they might not. Regardless of their survival, what will be the business model that funds journalism?

It’s entirely possible that journalism could see a new business model emerge. The old model required fixed payments from subscribers and advertisers that went to corporations (who then employ journalists). The new model could be completely different. It could rely on a small but loyal group of patrons that voluntarily give money to people or causes that they care about. Or the new model could be something else entirely. Or. journalism could die.

But that seems unlikely. The interest in good content is still strong. How much time do we spend perusing fascinating content on Twitter, Reddit or Hacker News? There is great content out there; if it’s paired with the right business model, there could be a resurgence in original reporting. Online, the barriers to entry for journalism are low. It’s never been easier or cheaper to run an experiment on funding journalism, and it seems as if journalists and startups are trying to solve this problem. To save content, you need to try to save content.

What do you think? What will be the business model that saves journalism? Compulsory payments? Donations? Subscriptions? Micropayments? More ads? Pay what you want? Nothing?

This post was written by Rohin Dhar. Follow him on Twitter here or Google. To get occasional notifications when we write blog posts, sign up for our email list.

Here’s the link to make a donation to charity and tell us what to write about next on the blog.