The NRA had a busy month. On April 17, the American Senate voted down legislation to regulate the purchase of guns. It was seen as a victory for the National Rifle Association (NRA), which lobbied against the bill.

On March 23rd of this year, the NRA also successfully lobbied the US Senate to defy an arms control treaty that the General Assembly of the United Nations (including the US representative) was passing. This treaty, the Arms Trade Treaty, is the first attempt to regulate the international sale of tanks, combat helicopters, and assault rifles that fuel wars around the world. Only Syria, Iran, and North Korea voted against it.

The US Senate signaled their opposition to the treaty by a vote of 53 to 46 to pass a counter-measure with the official purpose: “To uphold Second Amendment rights and prevent the United States from entering into the United Nations Arms Trade Treaty”. Senater James Inhofe of Oklahoma remarked:

“It’s time the Obama administration recognizes it is already a non-starter, and Americans will not stand for internationalists limiting and infringing upon their Constitutional rights.”

We’re beginning to get the idea that the NRA has some considerable sway over the United States Senate.

If guns sales in America is a big business, then the international arms trade is an enormous business. Approximately $11.7 billion worth of guns are sold in the United States and there are 30,000+ deaths in America each year tied to gun violence. The global arms trade, on the other hand, generates $85 billion in sales each year and can be tied to the deaths of hundreds of thousands of people every year.

There is profitable business to be had making weapons, shipping them off to other countries, and letting people kill each other with them. In this business of the international arms trade, the United States is the dominant player, with a market share of between 30% to 50% or more depending on how you calculate the figure.

The international arms trade is a very big deal that doesn’t get very much attention. Moreover, it doesn’t seem as if shipping weapons to other countries really furthers our own national security in any direct way. The United States may be more safe when we have tanks, but is the United States more safe when the Sudanese have tanks?

So, we thought we’d take a look. What is the international arms trade and who are the major players that profit from the business of blowing people up?

The Flow of Arms

There is no standard definition for the arms trade. It can include weapons from assault rifles to F-15 jet fighters, ammunition, and non-lethal equipment like Humvees and radar systems. The Arms Trade Treaty, however, limits itself to weaponry and ammunition. The players in the arms trade include governments, private companies, gunrunners, rebel movements, and terrorists.

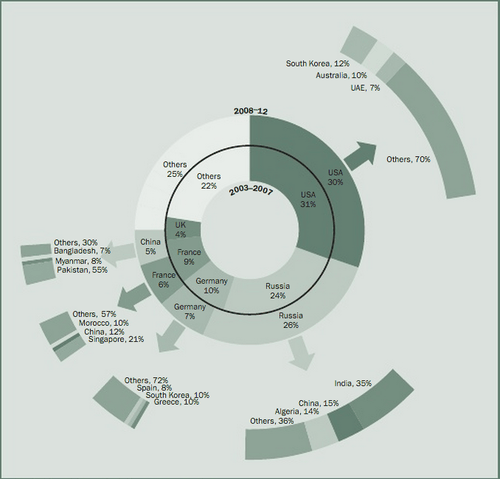

Source: SIPRI

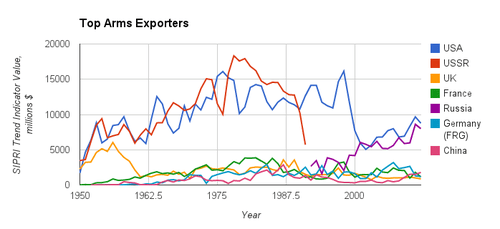

The international arms trade predominantly consists of developed countries selling to developing states. Since the Cold War, the five biggest suppliers have been the United States, Russia, Germany, France, and the UK. China, which overtook the UK as the number five supplier of arms in 2013, is the lone exception. The United States and Russia have the largest market share at 30% and 26% respectively for 2008-2012.

Source: SIPRI

These clear national distinctions, however, camouflage that the arms trade is very globalized. In 1994, The Economist noted that America “cannot put a single missile or aircraft up in the sky without the help of three Japanese companies.” Although security requirements tie producers of arms more tightly to their national governments, they source materials and parts from across the globe and set up subsidiaries abroad. The transport of arms is also fully outsourced to private companies.

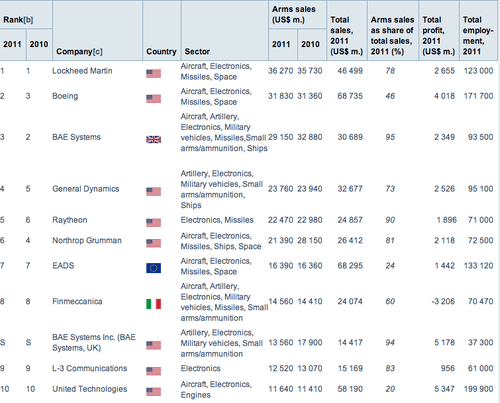

Among the 10 largest companies in arms production, 7 of the 10 are American. Lockheed Martin, the largest, employs 123,000 people and makes $36.27 billion in arms sales. The majority of those sales are from the American government, but Lockheed’s CFO estimated that 15% of its arms sales are foreign.

In 2012, India, China, Pakistan, Singapore, and South Korea accounted for 32% of arms imports. But the biggest importers are not a consistent group from year to year.

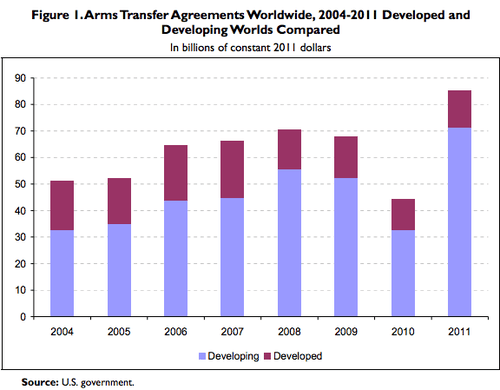

Nearly every country in the world imports arms – all but four in 2011. Even Vatican City imports submachine guns from Italy. But developing countries make up the majority of arms imports. From 2004 to 2011, arms transfers agreements to the developing world made up 68.6% of all agreements. It was 79.2% from 2008 to 2011.

With the exception of booming economies such as China, South Korea, and South Africa, very few developed countries can produce military technologies. According to the Stockholm International Peace Research Institute:

“Attempts by countries outside the traditional major producers to develop their own modern arms industries have typically had limited success. This is in large part due to the high technological barriers to producing modern major weapons systems and, in many cases, an inadequate civilian industrial base.”

Military technology has extremely high barriers to entry. China now has the world’s second highest military budget after the United States. Nevertheless, its first aircraft carrier, unveiled in 2011, is actually an old Soviet warship purchased from Ukraine with a ski-jump added to help planes take off.

The developing world relies on exporters for basic arms and supplies. Sudan’s Military Industrial Corporation, for example, is Sub Saharan Africa’s most advanced arms industry outside South Africa. It advertises its work selling ammunition, upgrading T-55 tanks, and producing machine guns. But all of its projects rely on foreign imports, designs, and assistance. The Corporation assembles light aircraft with Chinese and Russian assistance, the components of the machine guns likely come come from Iran, China, or Pakistan, and the tank upgrades were probably imported from China.

In sum, the global arms trade is a consistent flow of arms from a handful of developed countries to nearly every developing country in the world – countries who, in isolation, can produce very few arms. If the purpose of the United States Military and it’s weapons providers is to keep America safe, it’s unclear how shipping these weapons to other countries helps achieve that.

Legal Controls

A number of bilateral and international treaties do exist to control the spread and sale of weapons. The START treaties (Strategic Arms Reduction Treaties) call for Russia and the United States to reduce their nuclear stockpiles, the Convention on Cluster Munitions bans the use of cluster bombs worldwide, and the Ottawa Treaty bans the use of landmines.

But beside these exceptions, the only international regulation on the sale of arms is the application of an arms embargo by the United Nations. This is an extremely high bar. Embargoes are decided by the UN Security Council, and can be vetoed by any of the council’s 5 permanent members – China, Russia, the US, the UK, or France.

As a result, embargoes are rarely applied. From 2006-2010, 22 of Sub Saharan Africa’s 48 countries experienced armed conflict, but only 8 had arms embargoes in effect.

Even then, arms embargoes rarely succeed in slowing the transfer of weapons to conflict zones. One quantitative study found that only 40% of countries saw a reduction in arms imports during an embargo. Another report found little effect, other than that arms and ammunition “reached the embargoed targets only after travelling circuitous routes.” They cite a lack of political will on the part of members of the UN to enforce the embargo as a common cause of failure.

As a result, the continued supply of arms to embargoed war zones is common. A 2005 arms embargo on the purchase and use of arms in the Darfur region of Sudan, for example, was broken despite the world labeling the government’s actions in Darfur a genocide. Belarus, China, Russia, and Ukraine exported arms to Sudan for the conflict and Chad provided the separatist movements in Darfur with small arms.

National regulations of arms transfers seem more robust, but suffer from loopholes and inconsistent application.

In the United States the Arms Export Control Act and the Foreign Assistance Act regulate the sale of American arms. Private companies must apply for licenses as arms brokers and clear deals with the government. All deals must meet criteria such as furthering the security interests of the United States and “promot[ing] world peace.” The acts seek to prevent the proliferation of arms to undesirable third parties; the US is the lone state to attempt “end-use monitoring” to ensure the arms go to their intended recipient. Congress can block deals if it has the votes to override a presidential veto.

The United States is one of only 40 or so countries to legislate arms transfers. Nevertheless, Amnesty International finds that American regulation of arms transfers, although “generally considered a model for regulating arms brokering, includes exemptions that, in the real world, severely narrow its scope.” Namely, while the US focused intently after September 11 on monitoring the end use of arms to keep them from terrorists, it is still not very discriminate in providing weapons to autocratic leaders.

For government deals, this exemption is for programs deemed “vital to national security.” All these safeguards can be waived if the president or secretary of state decide that the deal is essential to national security. The clause was most recently invoked by Hillary Clinton to bypass legislative action from Congress to withhold $1.3 billion in military aid until Egypt completes democratic reforms.

In private deals by arms brokers, the most fatal exemption is to require no monitoring of the use of delivered weapons beyond an “end-use certificate.” With so few states verifying the use of purchased arms, all brokers need to circumvent an arms embargo is one corrupt military official willing to sign a document certifying his reception of the weapons as they are moved to another plane and flown off to blacklisted rebel groups or governments.

The Motives of Arms Suppliers

During the Cold War, the primary motivation of arms transfers was to gain political influence. The Soviets armed Communist governments and rebel groups, America armed the other side, and both plied non-aligned countries with military aid to court them.

After the Cold War, global leaders expressed optimism that the world could spend less on military budgets and reinvest that money in people. Military budgets did decrease. Expenditures in 1999 stood at only 55% of their 1989 Cold War level.

At the same time, however, arms transfers to developed countries exploded:

“Between 1989 and 1999, the major arms producers and suppliers exported and delivered worldwide no less than 16,000 main battle tanks; 43,000 artillery units; 30,000 armoured vehicles; 1,600 military ships and submarines; 5,200 combat aircrafts; 5,100 military planes; 3,200 helicopters; 47,700 surface-to-air missiles; 3,300 surface-to-surface missiles; and 3,200 anti-ship missiles.”

In the decade after the Cold War, developing countries accounted for 54% of military imports. That number jumped further to 68.5% in the decade since. So what happened?

The desire to achieve political influence and achieve national security goals does motivate a number of arms transfers. American military aid to Egypt began as a way to cement the 1979 Egypt-Israel peace treaty. Perceived allies in the War on Terror, such as Yemen, have received arms and military aid.

Pure profit is also a motive. Cash-strapped Ukraine, for example, earned $956.7 million selling small arms stockpiled during the Cold War to African countries. Countries can also use military aid to negotiate access to natural resources. This charge is mostly pointed at China’s arms transfers in Sub Saharan Africa. Although debated in the field, a Chinese arms exporter has “cited the ‘spillover effect’ of military trade in its efforts to get contracts for its subsidiary Zhenhua Oil Co. in several countries worldwide including Angola.”

The primary reason that arms transfers exploded to developing countries after the Cold War, however, is that it allowed arms industries to survive once the logic and funding of the Arms Race disappeared. The arms industry aggressively courted customers in the developing world. Their governments assisted them, as every arms deal reduced the unit cost of arms, and kept alive the manufacturing jobs that politicians loved to promise constituents.

The pace of deals was accelerated by the ease with which corruption greased deals. Amnesty International has noted that the arms trade is essentially a perfect storm for corruption – it involves large contracts, high barriers to entry, and confidentiality. Whether in the form of actual bribes, campaign contributions, a “revolving door” policy of government officials moving onto plush jobs in the private arms industry in return for favorable treatment, both exporter and importer government officials had incentives to green-light deals.

Much attention was paid to the awarding of lucrative, no-bid contracts to Vice-President Dick Cheney’s company Halliburton during the Iraq War. But two books, The Arms Bazaar and The Shadow World, are filled with enough examples of how corruption in the arms trade is systemic to make the most idealistic believer in government tear up their Hope and Change posters.

The incentives to push arms deals are so strong, agreements are often inked for unnecessary deals. In the words of Oscar Arias Sanchez, former president of Costa Rica:

“In 2006, the [Latin America’s] military spending was over US$32 billion, while 194 million people languished in poverty. Latin America has begun a new arms race, regardless of the fact that the region has never been more democratic; regardless of the fact that in the last century it has rarely seen military conflicts between nations; regardless of the fact that a host of dire needs in the fields of education and public health demand attention.”

The reluctance to turn down arms deals also means that exporters will sell arms to autocratic states right up to the point that the UN calls for an arms embargo. In 2010, the top two recipients of American arms were the United Arab Emirates and Saudi Arabia. Bahrain and Egypt continue to receive military aid despite documented human rights abuses against protesters.

Small Arms and Gun Runners

While America’s sales and transfers of military products like the multimillion dollar F-15 make it the dominant player in the arms trade, the fact that many of today’s conflicts are fought by belligerents without advanced weaponry means that the most impactful arms purchases often are relative blips in the arms trade.

The situation in Sub Saharan Africa demonstrates this point. It accounts for only 1.5% of major arms imports. Small arms like AK-47s constitutes the majority of purchases.

Although the simplest of arms, small arms are the most lethal. They are responsible for hundreds of thousands of deaths each year (60%-90% of all conflict deaths) and millions of injuries. The war in the Democratic Republic of the Congo is fought with small arms. But that has not kept it from being the most deadly war since World War II with over 5 million fatalities.

When more advanced weapons are sold, a very small order can have a major impact. The sale of two second-hand Mi-24 combat helicopters from Bulgaria to Mali in 2007 is a rounding error compared to deals between Saudi Arabia and the United States. But they had a devastating impact. The two helicopters, Mali’s first, killed dozens of Malian rebels during their first use in April 2008, likely leading to the rebels seeking a ceasefire agreement.

Given the importance but small footprint of light arms, monitoring and regulating their transfer, whether licit or illicit, is nearly impossible. In 2001, for example, a dhow – a wooden-hulled ship with a triangular sail – delivered 500 rifles, grenade launchers, and machine guns to a Somali warlord, despite an international embargo. Malian smugglers attach arms in waterproof sacks to the bottom of boats and float them up the Niger River. Former Liberian president and war criminal Charles Taylor trafficked arms by having soldiers and refugees walk them across the border one at a time.

This is also the environment in which gunrunners thrive. Victor Bout, the famed Russian smuggler who provided inspiration for Nicolas Cage’s character in the film “Lord of War,” was an entrepreneurial owner of an air-freight company delivering televisions and textiles to third-world capitals when his customers asked him to deliver weapons as well.

He began by delivering arms to the Afghan government to fight the Taliban – a legal act. In 1998, he began smuggling weapons (along with cooking oil and whiskey) to a rebel movement in Angola in direct violation of a UN arms embargo. From Bulgaria, Bout flew “crates of rocket-propelled grenades, AK-47s, and mortars, along with armored personnel carriers” to the rebel group. One deal was worth a hundred million dollars. At the same time, Bout delivered weapons to the Angolan government. Confronted about his double dealing by a reporter, Bout responded, “If I didn’t do it, someone else would.”

As Victor Bout showed, even when gunrunners smuggle across continents and through European airports, they can obfuscate their intent by mixing their weapon deliveries with legitimate goods. They also set up networks of front businesses and forge end-user certificates to avoid detection. Most perniciously, gunrunners like Bout have trafficked arms into conflict zones under arms embargoes without breaking the law. Syrian trafficker Monzer al-Kassem lived openly while defying arms embargoes by structuring his deals so that he never broke a law:

“Moreover, a weapons shipment can represent a violation of international law but still be perfectly legal in many nations. In setting up transactions, Kassar often acted as what is known as a “third-party broker.” From his home in Spain, he could negotiate between a supplier in a second country and a buyer in a third. The weapons could then be shipped directly from the second country to the third, while his commission was wired to a bank in a fourth. Kassar never set foot in the countries where the crime transpired—and in Spain he had committed no crime.”

Any attempt to inject a dose of ethics into the arms trade will have to deal with the fact that the arms responsible for most of the world’s deaths in violent conflict are so minor and easily smuggled.

Conclusion

The gun industry in America is a large and dangerous business. The global weapons industry is an even larger and more dangerous business. If the Arms Trade Treaty eventually passes, would the world become a safer and better place? Perhaps not, but it’s unlikely it would make the world a more dangerous place.

As the current difficulties of passing an arms embargo on Syria show, achieving international consensus on who should and should not be allowed to import arms is a difficult task – especially in a world where countries want to arm their geopolitical allies. The size of the arms industry and its potential for corruption also make attempts to regulate it especially vulnerable to special interests. Further, small arms, which are used in the majority of fatalities, are easy to smuggle. Proponents of the Arms Trade Treaty can make a strong case that current legal controls on international arms transfers are insufficient.

Opponents of arms control may argue for “peace through strength” or that not every ally will have a perfect human rights record in an imperfect world. However, the arms trade isn’t really about directly protecting national security. The arms trade is about the transfer of arms from the US, Europe, and Russia to the developing world in exchange for cash, in a process that can empower dictators, fuel wars, and facilitate human rights abuses.

Guns kill people. So too do tanks and bombs.

This post was written by Alex Mayyasi. Follow him on Twitter here or Google Plus.