If you follow the news, you may have heard that there’s a non partisan movement to stop locking up so many Americans. The New York Times recently wrote, “A bipartisan campaign to reduce mass incarceration has led to enormous declines in new inmates from big cities, cutting America’s prison population for the first time since the 1970s.”

Unfortunately for reform advocates, reports of progress towards ending mass incarceration have been greatly exaggerated.

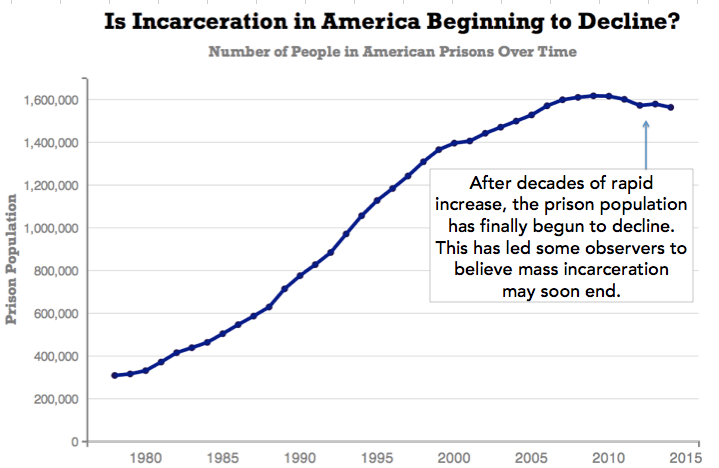

It is true that many conservatives and liberals now agree that America’s world leading incarceration rate is doing more harm than good. It is also true that that since 2009, there has been a small decline in the prison population (see the chart below).

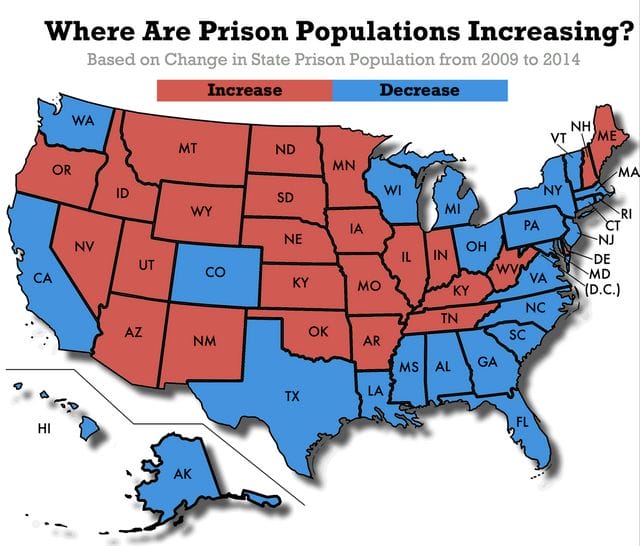

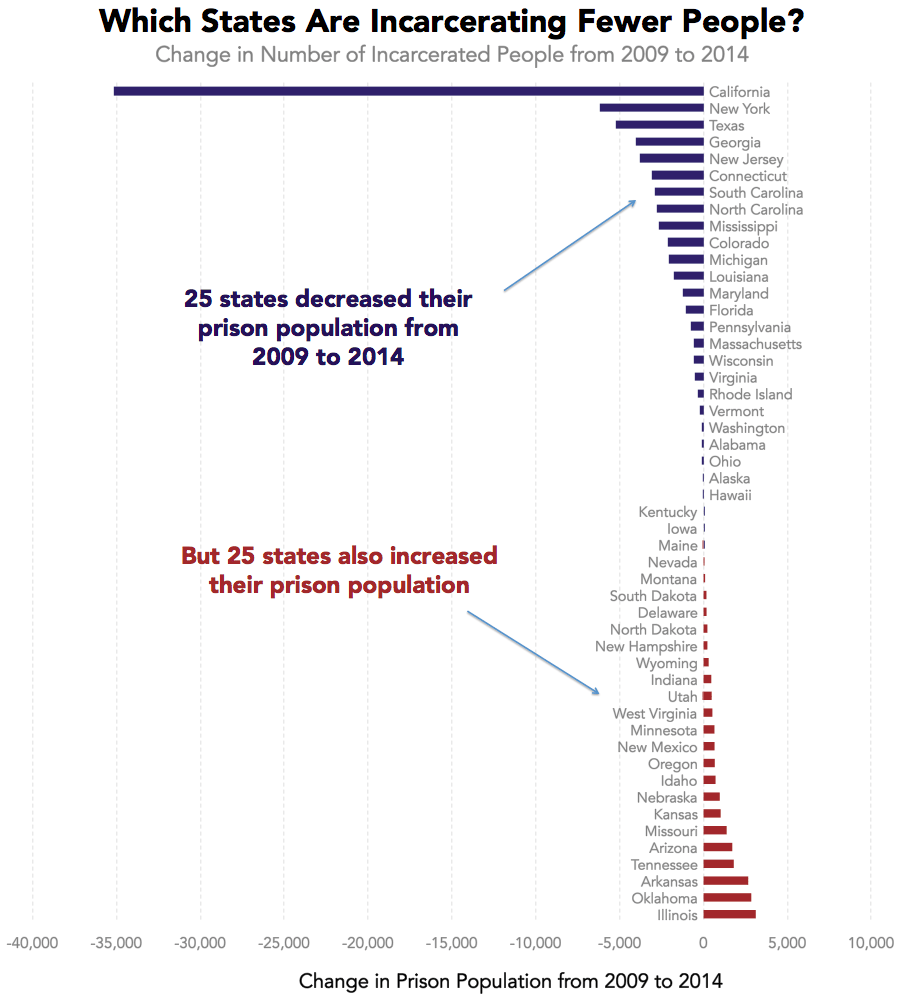

Yet this this national trend belies a larger truth. In large swaths of the United States, the prison population continues to rise. Since 2009, about half of all states have actually increased their prison populations.

The truth is that most of the reduction we’ve seen in the national incarceration rate is the result of a lawsuit that forced the state of California to reduce its prison population in response to to alleged human rights violations. California’s “decarceration”—which was not the product of some emerging bipartisan consensus—accounts for the vast majority of the national reduction.

Though widespread decarceration may be on its way, it certainly is not happening yet.

A court ruling forced California to decrease its incarceration rate in prisons like San Quentin (above).

In 2001, the federal class action suit Brown V. Plata was brought against the state of California for not offering sufficient medical care to the prison population. Among other claims, the suit alleged that inadequate care had led to the death of 34 inmates.

The case made it to the Supreme Court, which, in a 5-4 decision in 2011, upheld a lower court ruling forcing the state to lower its prison population in order to provide better healthcare. When the decision was made, California prisons held about 170,000 inmates—more than 200% above capacity and about the same number as Italy, Germany, and Spain combined. The court mandated that the state bring down the population to 137.5% of capacity within two years.

“The basic idea behind this decision was that if you bring down your prison population relative to capacity, that provides the state with an opportunity to provide adequate health and mental health care,” the economist Magnus Lofstrom told us. “Not surprisingly, [California] was not happy with this.”

Lofstrom, a Senior Fellow at the Public Policy Institute of California, has spent much of the last five years researching the impact of California’s response to the Brown V. Plata ruling. He explained that at the time of the ruling, California was facing fiscal challenges stemming from the 2009 financial crisis and did not have the money to build more prisons. This meant the only option was reducing the number of inmates.

The largest program to decrease the prison population was the Public Safety Realignment initiative (aka “Realignment”). The primary effect of the policy was to move the supervision of “triple nons”—non-violent, non-serious, non-sexual—offenders from the state to counties. In addition, recidivism was reduced by making it so that parole violators could not be sent back to state prison unless they committed a new felony (previously just missing a parole meeting could mean returning to prison). These reforms increased county jail populations, but not by nearly as much as they reduced the prison populations.

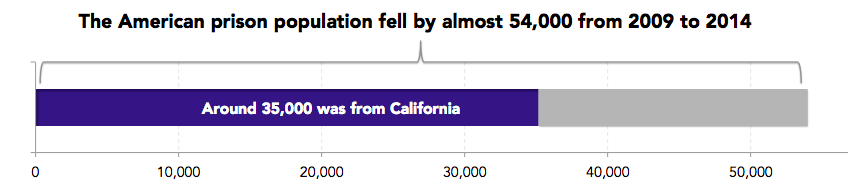

Compelled by the Brown V. Plata decision, California reduced its prison population from 171,000 in 2009 to 136,000 in 2014—a decrease of about 35,000. In that same period, the decline in the prison population across the entire country was 54,000.

Sixty-five percent of the reduction in the prison population from 2009 to 2014 came from California alone. If you removed the four states with the most substantial declines in their prison population—California, New York, Texas and Georgia—there would have been no decline at all.

In fact, during this period, just as many states increased their prison population as decreased it.

“There is a constant theme in criminal justice that we tell these national stories,” says Fordham Law professor John Pfaff. “But every area has its own pathology.”

Pfaff, who conducts empirical research on criminal justice trends, argues for a more locally focused view of what drives incarceration rates.

While federal reforms—such as the Fair Sentencing Act of 2010, which decreased the punitiveness of some drug sentences and the elimination of private federal prisons—receive a great deal of media attention, Pfaff argues that they have a limited impact on incarceration. Of the nearly 1.6 million Americans incarcerated in prisons, only about 200,000 are in federal prisons. “If we freed every single federal prisoner today,” says Pfaff, “we would still have the highest incarceration rate in the world.”

Pfaff’s research on the causes of mass incarceration shows that decisions made by local prosecutors and police are the most important drivers of the increase in country prison population. Specifically, prosecutors are much more aggressive in charging individuals with felonies today than they were thirty years ago—even for the same crime.

“I feel like the most important way to reduce incarceration would be to restrict the ability of prosecutors to file felony charges,” Pfaff said. “We need legally binding charging and plea bargaining guidelines like the ones judges operate under.”

Even within states, county policies differ dramatically. The Department of Justice recently released data to the New York Times showing which counties had more people sent to prison in 2014 than in 2006 (the two years for which data was released).

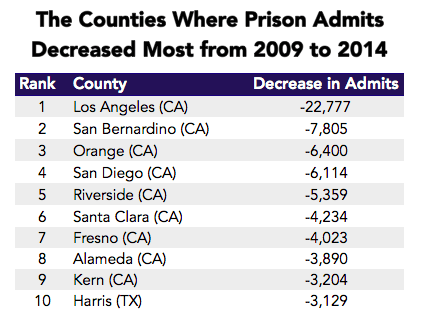

We examined data for the 1,000 counties that had over 50 people admitted to a prison in both 2006 and 2014. Our analysis shows that more counties actually increased the number of admits from 2006 to 2014 than decreased them. All but one of the ten counties with the largest reductions in admits were in California—the state legally mandated to reduce its prison population.

***

The perception that mass incarceration is on the decline across America is inaccurate.

The country’s prison population has declined since 2009 for the first time since incarceration rates began to rise in the last 1970s, but that is not a result of bipartisan reform. Rather, it is the consequence of a mandated policy forced on the state of California.

On the bright side for criminal justice reform advocates, some observers believe the experience of California will inspire widespread reform. Magnus Lofstrom and his colleagues found that California’s huge decrease in incarceration did not led to an increase in violent crime. This has saved California’s taxpayers tens of millions of dollars.

“The research over the last ten years quite consistently shows the incarceration rates we are experiencing in the US have a very limited crime prevention effect,” explains Lofstrom. He believes that this has caught the attention conservatives who are concerned with fiscal issues, and has led public sentiment towards reform. He points to the fact that Californians passed Proposition 47—a bill that reduced certain drug possession charges from felonies to misdemeanors—as a sign of this change in attitude.

Californians were forced into prison reform, and it turned out that most of them liked it. Perhaps the rest of the country will soon follow their lead.

Our next article explores the role insurance markets could play in reducing police on civilian violence. To get notified when we post it → join our email list.

![]()

Announcement: The Priceonomics Content Marketing Conference is on November 1 in San Francisco. Join speakers from Andreessen Horowitz, Slack, Thumbtack, Priceonomics and more.

Get your ticket here.