“She was born a slave somewhere in Tennessee, but lived to become one of the freest souls ever to draw a breath.”

~ Western film actor Gary Cooper

![]()

On a waning afternoon in 1902, the Silver Dollar Saloon — Cascade, Montana’s finest drinking establishment — was bustling with life.

Grizzled frontiersmen sat sheathed in thick tempests of smoke, slapping down playing cards and pounding shots of whiskey. Outside, tethered to posts, the horses seemed unaffected by the din: shouts, whistles, clinking glasses. Just beyond them, to the west, the golden plains of the Treasure State stretched up into the foothills of the Rocky Mountains.

It could have been a scene straight out of a John Wayne western, save for one abnormality: seated prominently among these men, chewing on a big black cigar and muttering profanities, was a 70-year-old African-American woman named “Stagecoach” Mary Fields.

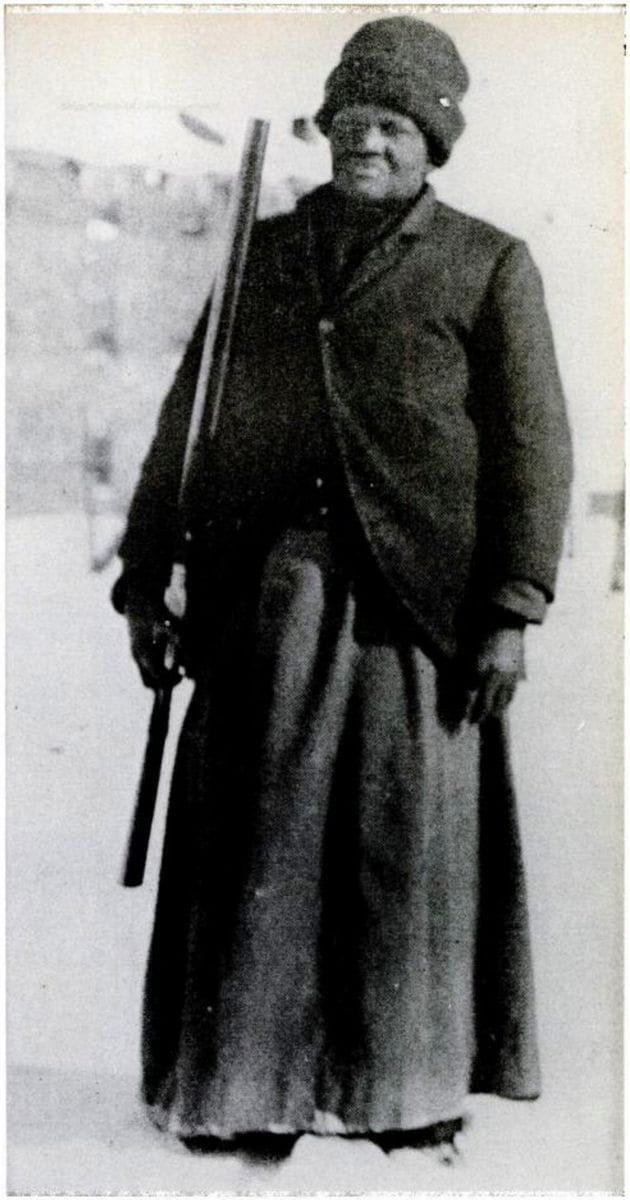

Once a plantation slave, Mary was now the most feared and respected person in the room. Six-feet tall and 200 pounds of muscle, she carried a .38-caliber Smith & Wesson, though she preferred to fight with her fists. She maintained a standing bet that she could black out any man with one punch. On this particular day, in 1902, she’d have the opportunity.

As Mary guzzled her beer, she spotted a man outside who owed her $2. She rose, marched outside, and, with a swift jab to the jaw, knocked him to the floor. The bar grew quiet as she returned to her table.

“His bill,” she declared, “is now paid in full.”

![]()

One of America’s early western pioneers, “Stagecoach” Mary Fields broke not just noses, but numerous barriers.

She was the first black woman to settle in central Montana, and also the first to deliver mail for the U.S. Postal Service. She bypassed many “conventional restrictions on race and gender,” demanding to be treated as equal. She possessed every quality of the great western heroine: self-assuredness, determination, independence. Yet, in the whitewashed narrative of American folklore, she has been largely forgotten.

This is her story.

Thirty Years a Slave

Mary Fields, in the doorway of her later home (c. 1880s); The Cascade County Historical Society

Like many African-Americans in the early 19th century, Mary Fields’ exact birth date was not recorded. Most accounts place her birth around 1832, on a slave plantation in Hickman County, Tennessee.

At the time, slaves made up 25% of Tennessee’s population, and they were the unwilling backbone of the state’s agricultural production. Tennessee was home to many of the country’s largest slaveholders, including then-President Andrew Jackson, who relied on the labor of 150 black men, women, and children to run his 1,000-acre Hermitage in Nashville.

As a young girl, Mary outgrew the boys her age and, due to her size, was ordered to work in the cotton fields. By her 18th birthday, she was 6’0” and “well over 200 pounds” — an imposing, muscular figure whom no one dared reckon with. She gained a reputation for independence and fearlessness.

Around this time, Mary formed an unlikely friendship with one of her master’s acquaintances — a white woman by the name of Sarah Theresa Dunne. “The two women,” writes historian Tricia Wagner in African American Women of the Old West, “were as different as night and day”:

Sarah Dunne had a fair complexion and blond hair and blue eyes, and was descended from a wealthy Irish family. Mark was dark skinned with black hair and dark eyes, the child of slave parents. Sarah was frail and delicate; Mary was strong and sturdy. Sarah was educated early in life; Mary became literate only years later. Sarah was refined and patient; Mary was rough and quick-tempered.”

Despite these cultural and personal differences, the two bonded and, by all accounts, became close friends.

Robert E. Lee, the steamboat on which Mary briefly worked (c. 1895); via Leelinesteamers

With the ratification of the 13th amendment in 1865, 33-year-old Mary became a free woman. For several years, she worked odd jobs aboard the steamboat Robert E. Lee, once leading the vessel to victory in a race down the Mississippi River. At some point, Mary fortuitously connected with the Chief Justice of the Supreme Court, Edmund Dunne, who informed her that her old friend, Sarah, had ventured to Toledo, Ohio and become a nun with the Ursuline Catholic Convent. With little hesitation, Mary resolved that she would do the same: she packed her belongings and headed north.

Throughout the 1870s, Mary dedicated herself to the convent, enjoying a life of relative peace. She took great pride in tending the garden, guarding it with militant scrutiny. (“God help anyone who walked on the lawn after Mary cut it,” wrote one nun.) For this work, she was given free housing and meals, and paid a sum of $50 per year ($1,200 in 2015 dollars). Like the sisters, she dressed in all black, “wearing a black apron over her black dress…and donning a black skullcap.”

In 1884, Sarah Dunne, by then known as Sister Amadeus, headed west to Montana to help Jesuit missionaries build relief centers for displaced Native Americans. Mary stayed behind — but not for long. When she got word, one year later, that her friend had fallen ill, the 53-year-old left everything behind and braved the 1,600 mile journey westward.

Terror of the Countryside

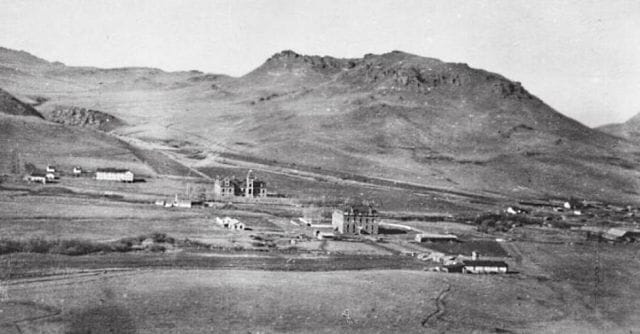

St. Peter’s Mission, outside of Cascade, Montana (c. 1900); via Wikipedia

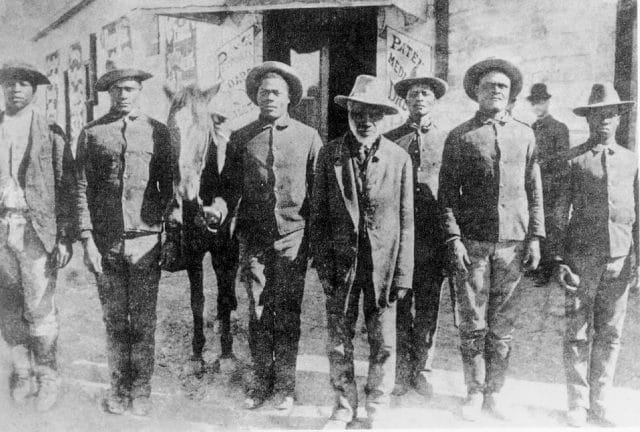

In the history of the American Wild West — a history immortalized by the squinting visages of John Wayne and Clint Eastwood — black frontiersmen/women are often forgotten.

“Their presence was ignored when scholars, textbook writers, and movie and television writers spun their white frontier tales,” says author William Loren Katz. “Black men and women rarely appear [in these mediums], but they were there all over the west.”

In the mid to late 1800s, thousands of black pioneers traveled west. They carved out lives as “explorers, trappers, cowboys, ranchers, farmers, gold miners, stagecoach drivers, scouts, cavalrymen, outlaws, lawmen, schoolteachers, and saloonkeepers.” In the free-for-all plains, they were afforded freedom from the oppressive south.

“As a cowboy you had to have a degree of independence,” says retired history professor Mike Searles. “You could not have an overseer, they had to go on horseback and they may be gone for days.”

Arriving in Cascade, Montana in 1885, Mary Fields was the first black woman to ever set foot in the small town.

After nursing Sister Amadeus back to health, Mary spent the next 8 years building the sisterhood a convent, three stone buildings, and a church. Refusing the assistance of men, she’d carry monumental loads of stone and lumber on her back, unassisted. When she finished the construction of St. Peter’s Mission, just west of Cascade, she settled there with the sisters and took on the duty of hauling freight on a stagecoach.

At 6’0”, 200 pounds, Mary Fields was an intimidating figure with a kind soul (c. late 1880); The Cascade County Historical Society

As the only black woman in these parts, Mary sometimes attracted unwanted attention — but she refused to take shit from anyone and “readily took on” those who provoked her. One historian writes:

“While Mary preferred to settle her arguments with her fists, it was well known that she carried a .38-caliber Smith & Wesson pistol under her apron for protection when she drove the freight wagon…it was said she ‘couldn’t miss a thing within 50 paces.’ Reliable as she was, she saw deliveries through and would take on anyone who prevented her from doing so.”

To locals, she was an enigma. “She drinks whiskey, and she swears, and she is a republican,” wrote one Cascade schoolgirl, “which makes her a low, foul creature.” In due time, Mary became known as the “Terror of the Countryside,” a woman who’d exact vengeance on any creature that spited her. An army captain who visited St. Peter’s Mission in 1887 recalled one such incident:

“A skunk invaded the chicken house, killed 62 of Mary’s choice chickens, and piled them up in a heap. With a spirit of indignation and satisfaction, she carried the animal to [a priest] and told him of the tragedy. Father Lindesmith inquired: ‘Mary, didn’t you receive the odor of his wrath when you killed him?’ ‘Ah, no Father,’ she replied, ‘I killed him from the rear.’”

Men learned to respect Mary the hard way. After one man verbally insulted her, she “pelted” him with stones until he receded, crying for help. On another occasion, in 1894, Mary challenged a another man to a duel; she shot a bullet so close to his head that he backed down and never spoke to her again. The Great Falls Examiner, a local paper, once declared that Mary “broke more noses than any other person in central Montana,” and that any man who challenged her was a hard-headed fool.

When the convent’s bishop heard of these antics, which strayed far from his conception of Victorian manners, he was none too pleased. Mary Fields was immediately ordered to leave.

Exiled from the community she’d built with her own hands, she briefly tried her luck in the restaurant business. But she was generous to a fault, gave away too many free meals to sheepherders, and ultimately went broke twice.

Hearing of Mary’s struggles, Sister Amadeus secured her friend a job as a U.S. Postal Service worker.

A Carrier Who Broke Barriers

Black cowboys in the American west (c. 1890s); via UCSD

Delivering mail in the Wild West was not for the soft-hearted or weak-willed. It was a job that carried immense risks and required long journeys on horseback through hostile territories. At the time, there was a saying in the Postal Service: “The horse and rider should perish before the [mail pouch] did.” A successful delivery was more valued than life itself.

As such, it was widely considered a job for men. Women, writes USPS, were thought to be incapable of handling the rigors of mail delivery:

“In the 1800s, carrying mail was not only physically demanding, but carriers, with their regular schedules, were potential targets for thieves. Women were popularly regarded as delicate and fragile, and those who carried mail were seen as larger-than-life legends in their own time.”

“Delicate” and “fragile” were not words that described Mary Fields. Out of all applicants, the 60 year-old was the fastest to hitch a team of six horses, outpacing men half her age. With her hiring, she became the second female — and the first African-American woman — mail carrier in the history of the Western United States. Her route, a 19-mile stagecoach ride between Cascade and St. Peter’s Mission, allowed her to return daily to the very place from which she was “exiled.”

Early Postal Service men en route to delivery; c. late 1800s; via USPS

Around Cascade, the lively mailwoman became known as “Stagecoach Mary.” When she rolled into town, writes one historian, she made her presence known to all:

“With a jug of whiskey by her foot, a pistol packed under her apron, and a shotgun by her side, [she] was ready to take on any aggressor. The shotgun she toted was one of the most feared of guns. It could cut a man in two at short range, and Mary wouldn’t hesitate to do so.”

Through rain, sleet, and snow, Mary delivered mail.Not once did she miss a day of work. On days when the snow was too deep for horses, she’d strap on snowshoes and haul the sacks on her shoulders. Like her male cohorts, she placed the highest value on seeing that her deliveries arrived without fail. African-American Women of the Old West recounts one instance:

“While she was en route one day, a pack of wolves frightened the horses, and the stagecoach overturned. Mary held a vigil all night, keeping the hungry wolves at bay with her pistol and shotgun. At daybreak, she was found alive, the mission’s supplies still intact.”

For nearly a decade, Mary faithfully served the Postal Service — a duty that earned her a legendary status around town. In a span of 15 years, “Stagecoach” Mary Fields had gone from Cascade’s outsider to its most respected citizen.

Don’t Mess With Mary

Mary (far right), with Cascade’s baseball team (c. late 1800s); The Cascade County Historical Society

At the age of 70, Mary retired from the Postal Service and settled in Cascade. But she was not ready to cede to old age.

With the assistance of wealthy patrons, she opened a laundry business. Town members, remembering how generous she’d been in giving out free food at her restaurant, paid it forward by supporting her. After a fire devastated her residence, people from all walks of life gave whatever they could — housing, food, clothing — to assist her. Though she never knew her real birthday, she’d observe it twice per year, whenever she pleased; on these days, the schools shut down to celebrate with her.

When she took a liking to the town’s baseball team, they invited her to attend the games as a guest of honor. She traveled the state with the players, presenting both teams with handmade boutonnieres after each game.

Mary was so well-liked that Cascade’s mayor, D.W. “Bill” Munroe, gave her special permission to drink at the saloons during a time when women weren’t allowed inside the establishments. She spent long hours talking politics and sports, and drinking barrel-chested men under the table. At 80-years-old, she’d still challenge anyone she didn’t like to a fistfight — though few men ever took her up on it.

Mary Fields’ grave marker (1914); The Cascade County Historical Society

This lifestyle caught up to Mary. Eventually her health declined, and she was brought to Columbus Hospital. On December 5, 1914, she succumbed to a severe case of edema.

In the wake of her death, both town papers ran her eulogy on the front page. Her funeral service was the largest in town history, drawing nearly every Cascade resident. She was laid to rest along her old mail route at the base of the mountains leading to St. Peter’s Mission. Until her death, and for some 40 years thereafter, she was the only black person to have ever resided in Cascade.

Years later, in 1959, western film star Gary Cooper, who grew up in Montana, recalled meeting Mary as a child and being too timid to speak. “She was born a slave somewhere in Tennessee,” he wrote, “but lived to become one of the freest souls ever to draw a breath.”

![]()

In our next post, we explore the incredible rise in the number of songwriters who claim credit for pop hits. → join our email list.

![]()

This post was written by Zachary Crockett. You can follow him on Twitter here.