In America, the pet industry is big business. Americans own over 86.4 million cats and 78.2 million dogs. The number of households that have pets even tops the number that have children. In 2011, Americans spent nearly $51 billion on pet expenditures.

Pets are a beloved member of American families. Our love affair with dogs and cats has produced luxury pet spas, home-cooked doggie meals, and countless children begging their parents for a pet. Despite the adoration Americans have for pets, however, we exterminate three to four million of them each year in shelters across the country. We kill them by lethal injection.

We find this perplexing. Americans love pets, treat them as family members, and kill millions of them. Our relationship with pets seems to be an odd juxtaposition of compassion and cruelty. What’s going on with the pet industry in America?

Where do all these pets come from? Who profits from breeding them? Why do we keep killing them?

Where Do Puppies and Kittens Come From?

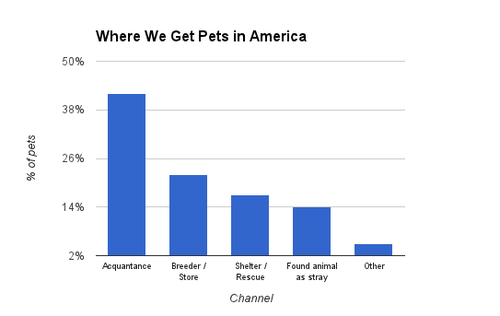

American families keep approximately 165 million dogs and cats as pets, and seventeen million Americans acquire a pet each year. The majority of these come from outside of formal channels. Forty two percent of pets are acquired from an acquaintance, and an additional 14% are strays – mostly cats (there are 70 million plus stray cats and dogs in America).

Through more formal channels, 22% of dogs and cats are purchased from pet stores or commercial breeders and 17% are adopted from a shelter or rescue organization.

Data Source: Oxford Lafayette Humane Society

Pets get abandoned. At any given time, approximately six to eight million pets are in a shelter, the modern, more humane equivalent of dog pounds. They attempt to return lost pets to their owners and rehabilitate dogs and cats for adoption. To find them good homes, many perform background checks or even make stringent demands on owners: a fenced in backyard, an understanding of pet ownership, and a commitment to obedience training and being home during the day.

Only half of the pets that move through shelters every year find homes. Since shelters do not re-release animals for public safety reasons and for the good of the pet, they would fill up until conditions are unbearable. Instead, the other half are killed. That means three to four million are put down each year.

Given how quickly shelters fill up, veterinarians and pet advocacy groups recommend that dogs and cats be spayed or neutered to combat overpopulation. Shelters, rescue organizations, and breeders seen as “responsible” all do. This is often mandated by local law. Many pet stores, breeders, and private owners do not. This crowds out the market for rescued and stray pets, indirectly contributing to high euthanization numbers. Every puppy sold or given away, the argument goes, makes it more likely one in a shelter will be put to death.

But the focus on overpopulation can also obfuscate the cause of euthanizations. Of the pets received by shelters, 30% to 50% come from owners relinquishing their pets, and the rest are picked up by animal control. The most common reasons cited by owners leaving their pets? They were moving, the landlord did not allow the pet, they had too many animals, or they could not afford the cost of food and veterinary care. Regardless of the reason, if you turn in your pet to a shelter, it’s a coin flip whether it will end up dead or with a new family.

Breeding and Overbreeding

If you don’t get your pet from a shelter or friend, breeders are the other option.

A small number of them have a business model resembling an artisanal shop: they breed a small number of (usually) purebred animals every year. They also maintain an ethos of professionalism and concern for their animals’ welfare; they specialize in one breed, work to maintain its purity, and screen their customers to vet out irresponsible pet owners.

These breeders can raise their dogs in idyllic conditions of sunny farms, financed by the high premium placed on purebreds. But the obsession with purebreds, especially in dogs, can go too far. The inbreeding done to select certain characteristics for dogs, as well as the highly exaggerated features of some breeds, can result in genetic and medical problems.

They range from mild – the popular labrador breed almost invariably suffers from eye and knee problems – to extreme: the bulldog’s large head, flat face, and wrinkled snout leave it unable to mate or give birth without a caesarian section. They can barely breathe and exercise. One study on the problems bulldogs face concluded, “Many would question whether the breed’s quality of life is so compromised that its breeding should be banned.”

The Pet Factories

The vast majority of dogs that are bred to be sold do not emerge from utopian pastures – they come from commercial breeders.

There are anywhere from 2,000 to 10,000 commercial breeders in America that produce approximately two million animals a year, mostly dogs. Critics call these large scale dog breeding operations “puppy mills” – a term they apply to any breeder that places profits over the well being of their dogs.

The United States may be already overpopulated with dogs and cats, but breeding offers a serious potential for profit. A large dog breeding operation is capable of six figure profits.

The average female breeding dog can produce 9.4 puppies per year. Puppies can command prices north of $1,000, especially if they are purebred. An average, aggressive puppy mill may have 100 female dogs and sell their puppies for $500 each wholesale or more retail. That operation will make almost half a million dollars in revenue per year and each dog will generate approximately $4,700 per year.

This is a decent amount of revenue per dog, but it could easily be eaten up by the costs of pet care. To maximize gross margin and profit, it’s critical these puppy mills keep their costs low.

How Puppy Mills Maximize Gross Margin

Looking into the operations of commercial breeders reveals pretty disturbing practices. The cold logic of profit maximization means these businesses can only profit by minimizing their expenditures on the animals they use for breeding.

Wikipedia paints the picture:

Puppy mills usually house dogs in overcrowded and unsanitary conditions, without adequate veterinary care, food, water and socialization. Puppy mill dogs do not receive adequate attention, exercise or basic grooming. To minimize waste cleanup, dogs are often kept in cages with wire flooring that injures their paws and legs. It is not unusual for cages to be stacked up in columns. Breeder dogs at mills might spend their entire lives outdoors, exposed to the elements, or kept inside indoor cages all their lives. Oftentimes, after the breeder dog has reached the age of 4 years, it is no longer needed and killed. Sometimes the puppy mill owners will have a contact person who collaborates with rescues. The rescue will receive a phone call with the number of breeder dogs and types. The rescue then can save the breeder dogs from death. Once adopted, it can take a year or more for the dog to relax and allow human touch.

A number of rescue organizations have performed raids, and the accounts are heartbreaking: stacks of wire cages and crates crowded with dogs, rescuers in gas masks handling scared animals, and sick dogs with matted hair, skinny bodies, and glazed eyes.

These raids occur on the basis of compelling evidence of animal cruelty. But the average puppy mill is not actually illegal. One minimum standard under the Animal Welfare Act, the sole federal law regulating these breeders, only requires that an animal be kept in a cage six inches longer than its body in any direction – even if never allowed out of the cage. As a result, some three thousand puppy mills, which only meet minimum standards like these, are certified and inspected by the US Department of Agriculture. Meanwhile, mills selling directly to the public, rather than through another seller, are not subject to any federal law, and often to no state law.

As a result, pet advocates assert, almost any puppy bought from a pet store or online (or from any breeder that does not insist on a site visit to see the puppy with its parents) came from a puppy mill. In a famous piece of reporting, the owner of a dog rescue association took Oprah to a pet store. They played with a few adorable puppies, then tracked their parents to puppy mills like the ones described above.

These mills sell millions of dogs per year. By selling pups through brokers, pet stores, or online, breeders can sell puppies without customers ever being wise to the plight of the puppies’ parents. Auctions throughout the Midwest allow breeders to swap dogs. Unlike many Americans, they view animals dispassionately as tools. One auctioneer asked his audience, “… where else you gonna find something to produce you over $2,000 gross in a year?” and reminded everyone that the dogs, “Got their whole lives in front of ‘em to work for ya…”

Breeders do not need to maintain even minimum federal standards: Internal audits of the USDA have consistently found that they are unable to effectively monitor dog breeders. In an extreme example, inspectors found dogs that resorted to cannibalism, but did not immediately revoke the breeder’s license, while other serious violations resulted only in warning after warning.

A rare study on pet shops and puppy mills in California found that 44% of those visited had sick or neglected animals” and 25% “did not have adequate food or water” for the animals. There is every reason to suspect that outside of California, in states like Pennsylvania and Missouri where the majority of mills exist in a climate of less animal cruelty concern, those numbers are much worse.

A Cash Crop

Pets have been around for a long time. In Europe, many dogs escaped their kennels and breached their owners’ homes centuries ago. Mary Todd Lincoln, when asked about her husband’s hobbies, described them as follows: “cats.” But while pets experienced a life of comfort and love in 19th century America, the view of dogs, cats, and other animals as worthy of respect and care is a relatively recent phenomenon.

After the Civil War, as urbanization began to rapidly move Americans off farms and into cities, selling pet animals to consumers became an industry serving the middle class. Attitudes toward pets followed a “Victorian ethic” by which compassion for animals was seen as civilized and cruelty as “one outward expression of inward moral collapse.”

We might assume that today’s pet owners, who lavish as much attention on pets as their own children, are the height of pet adoration. But the 1800s saw devotion every bit as maniacal. According to one inspired account:

The most inspired pet-keeping was surely practiced by the Rankin children of late 19th-century Albany, who turned a hutchful of rabbits “rescued from their fate as someone’s dinner” into a carefully documented kingdom that was reorganized as a republic, complete with a declaration of independence, a census, a postal system and taxes. Over the years, the Bunnie States of America spun off a map company and a medical college.

This co-existed, however, with inhumane treatment for animals not kept as pets. The phrase “dog days of summer” took on new meaning as city-dwellers systematically hunted down dogs in return for bounties to prevent the spread of rabies; Manhattan’s stray dogs were caught, locked in a cage, and lowered into the East River to be drowned on a daily basis. Americans generally justified this cruelty as part of the “natural order.” Man had dominion over animals, and could treat them as he saw fit. The majority of Americans, even pet owners, saw no reason to afford any rights to a stray or working animal.

The first puppy mills arose after World War II. According to dog rescue organizations, the US Department of Agriculture encouraged farmers to breed puppies as a new “cash crop” for the burgeoning pet store market. No oversight or laws existed on the practice. Unsurprisingly, farmers that had been devastated by the Great Depression, survived World War II, and used animals as tools did not prioritize the comfort of the dogs. They remained locked inside refashioned chicken coops, without access to veterinary care or “socialization” with humans and other dogs.

While puppy mills had poor conditions, the view of puppies and dogs as a commodity meant that they were euthanized and discarded in large numbers. In the words of the president of a New England animal shelter:

“In the past, it was acceptable to throw an animal away, the way you would an old television set. You would just bring them to the shelter and dump the old dog you don’t want anymore.”

This was equally true of shelter workers:

“For a long time, it’s just what you did. [Animals] came in; you killed them. No one thought that was wrong.”

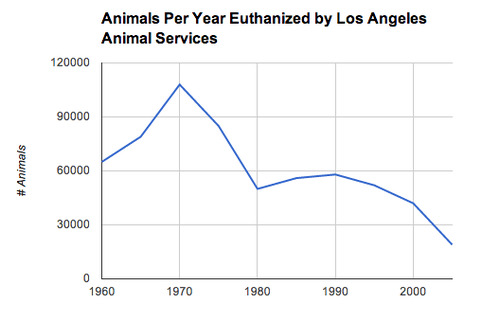

Pet owners felt no qualms dropping off their unwanted dogs, while pet stores dropped off puppies that grew too old to sell and breeders discarded animals that could no longer breed. By 1970, shelters – overcrowded with adoptable but unwanted dogs and cats – euthanized over 20 million animals.

Four Decades of Change

In 2011, the number of animals euthanized stood at approximately three million, an incredible decrease from the 20 million mark in 1970, especially considering that the number of pets has doubled from 80 million dogs and cats to 160 million, according to the American Society for the Prevention of Cruelty to Animals.

Data source: Los Angeles Animal Services

The movement to spay and neuter dogs and cats – sterilize them to decrease the population of unwanted animals – began in 1971 when a Los Angeles shelter opened a low-cost spay/neuter clinic. It framed sterilization as an issue of compassion. In its first four years, spaying and neutering increased from 10% to 51% in Los Angeles among licensed dogs. Crucially, the clinic and its followers not only spread spaying and neutering as a norm (both among shelters and through outreach programs), but also subsidized the cost of the procedure – a crucial point for low-income pet owners considering that sterilization costs several hundred dollars today.

States and local government also began mandating the practice of spaying and neutering. Some require pet owners to sterilize their pets or face a penalty; others mandate it. A minority require pet stores to spay and neuter all dogs and cats. The laws are not uniform, but 30 states have some form of spay/neuter laws. As a result, 78% of pet dogs are spayed or neutered, and sterilization is considered “a standard practice of care,” with unsterilized dogs an exception among pet owners where it was once the rule.

The improving lot of pets can also be linked to the establishment of responsible pet care as a norm. Whereas pets were once a commodity or tool to be used by people, a myriad of organizations now publish manuals that sternly lecture on the responsibilities that come with the “privilege” of pet ownership. Online searches on where to buy a puppy return hundreds of articles on the evils of puppy mills and retail pet stores. Anyone posting to an email list or online forum asking where to give up their pet can expect to face a horde of self-righteous, finger-wagging pet advocates.

With increased care for the welfare of pets came increased resources to improve their treatment. The amount shelters spent on animal protection increased from roughly $1 billion to $2.8 billion from 1975 to 2007, accounting for inflation. Rescue and advocacy organizations have proliferated. Petfinder, for example, offers links to nearly 14,000 adoption groups.

Increased legal attention has focused on puppy mills in addition to spaying, neutering, and animal cruelty. Many local governments have placed more stringent conditions on dog breeding than the federal minimum, and a number of cities have banned the sale of dogs and cats in pet stores outright to prevent the sale of puppy mill pups: LA became the biggest city to do so in 2012, joining 27 other major cities.

The past four decades have seen dramatic improvement in the lot of America’s dogs. Euthanization has fallen dramatically thanks to legal action, increased resources, and the norms of responsible pet care, which have also taken aim at puppy mills and animal cruelty.

The recession has, however, reversed some of these gains. When we visited the the San Francisco Department of Animal Care, which is mandated to accept any dog in San Francisco for any reason, they described a significant increase in the number of dogs dropped off by owners who could not afford to buy food for their dog or pay for veterinary care, as well as people who tried (and failed) to make cash amongst the hardship of the recession by breeding chihuahua and pitbull puppies.

A Dog’s Life

America’s relationship with pets is a mixed bag. People clearly love their pets, yet we kill millions of them a year. But the number of pet euthanizations keeps dropping as more pets are sterilized, more people adopt, and fewer people treat pets like commodities. If 1970 marked the high-water mark in pet cruelty, massive strides have been made since then.

But focusing only on euthanizations misses part of the story. Hidden behind a cloak of respectability, pet stores and brokers continue to sell puppies that came from exploitive “puppy mills.” Pet-loving Americans are mostly ignorant to the plight of the cute, cuddly creatures that they love to croon over. Many of our phones, shoes, and computers come from factories with abysmal conditions. Perhaps it’s not surprising that many of our pets do as well.

This post was written by Alex Mayyasi. Follow him on Twitter here or Google. He owns a rescued golden retriever mix named Sienna, which is why there are no pictures of cats in this post.