The human kidney is the body’s filter. It cleans 180 liters of liquid per day, retaining the good stuff and expelling the bad. Most fortuitously, humans are born with two kidneys. If one of them becomes damaged, the other one can pick up the slack. If both your kidneys fail, however, your body will fill with harmful toxins. Without medical intervention, you’ll die within weeks.

Almost nine hundred thousand Americans suffer from End State Renal Disease (ESRD), meaning that both their kidneys have failed. Thankfully, over the last half century, science has technically triumphed over kidney failure. If both your kidneys fail, you can receive a transplant from a donor and live a fairly normal, healthy life. The technology for kidney transplants has gotten so good that the donor and recipient just need to share the same blood type. Surgeons and anti-rejection drugs can handle the rest. Since almost everyone has a spare kidney, the supply of potential donors is plentiful.

And yet, over 5,000 people die in the US every year while waiting for a kidney transplant. This is puzzling because only 83 thousand people in the United States need a new kidney, compared to hundreds of millions of potential donors. And yet, the average person with failed kidneys remains on the transplant waitlist for 3-5 years. In the meantime, they’re hooked up to dialysis machines several times a week at an annual cost of approximately $75,000 per year. Kidney transplant surgeries typically pay for themselves within one to three years because the need for dialysis is eliminated by the new kidney.

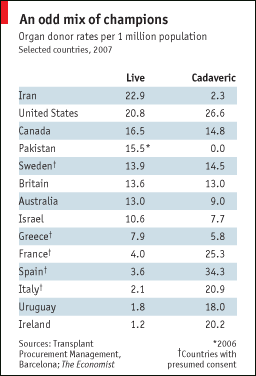

So why do people die from ESRD while waiting for a kidney transplant? The answer is well known – not enough people volunteer to donate a kidney. This is true in the United States and every other country in the world (with the possible exception of Iran). People simply don’t volunteer to go into surgery and give up their organs. Even when they’re dead, most people (or their families) hold onto their kidneys instead of donating them.

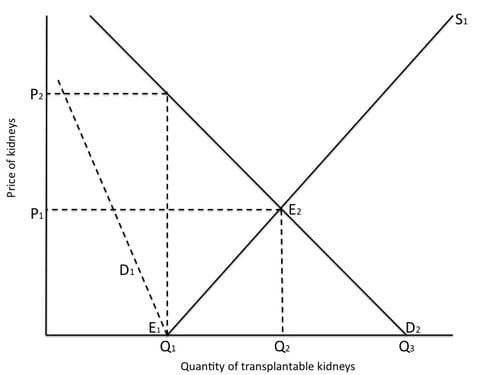

Economists have long suggested that this kidney shortage is easily solvable. If you need more kidneys for transplants, just start paying people to provide kidneys. At the right price, kidney donors will be lining up. Opponents of this view argue that creating a free market for kidneys would be exploitative and immoral. Would we want to live in a world where the poor sell their organs to the rich?

But maybe this “efficient” versus “moral” debate about how to allocate kidneys is a false dichotomy. Solving the kidney shortage by paying people doesn’t have to mean creating a laissez-faire market for organs.

In order to save thousands of lives every year, we can keep the current kidney donation system entirely in place with one major exception – the US Government should get into the business of buying kidneys. Taxpayers will actually save money and thousands of lives will be saved every year.

Perhaps it’s time we start allowing the government to harvest our organs.

The Growing Shortage of Kidneys in America

In the United States, over 20 million people have some sort of chronic kidney disease (CKD). Approximately 871,000 Americans suffer from the most severe form of chronic kidney disease, End State Renal Disease. Roughly one half (398,000) of these patients are on dialysis each year. It costs approximately $75K a year to keep each of these patients alive.

Dialysis is a brutally difficult but completely necessary experience for people with failed kidneys. Most patients have to be plugged into a machine at a facility three times a week for three to five hours each time. The machine simulates kidney function, but it’s an imperfect substitute. While normal kidneys remove toxins from the blood continuously, the dialysis machine does so for a few hours every 48 hours. When the patient is not plugged into a machine, these toxins build up, causing the patients to feel tired and in a state of mental fog until the next dialysis session.

Being on dialysis is hopefully a stop gap measure to keep a patient alive till they can get a kidney transplant. Of the nearly four hundred thousand patients in the United States, only 83,000 of them were on the the waitlist for a kidney transplant. Many people on dialysis are too old or sick to qualify for a transplant.

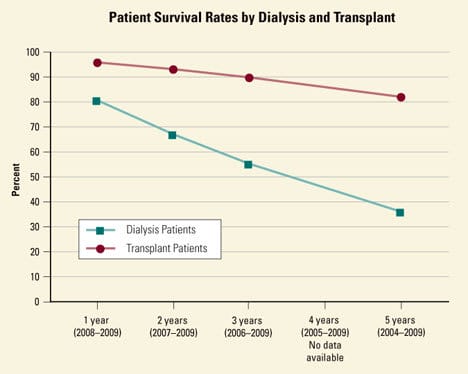

Patients that live long enough to get off the waitlist can get kidney transplants and live fairly normal, healthy lives. It’s estimated that these patients will live 10-15 years longer than if they stayed on dialysis. The transplanted kidneys start working almost right away for the patient. Over time, they are far more likely to live because of the transplant.

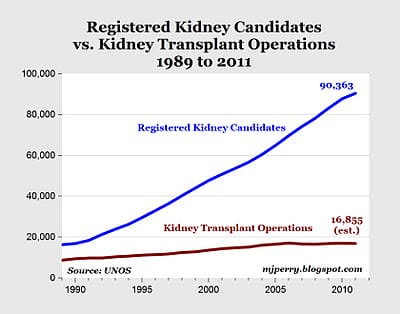

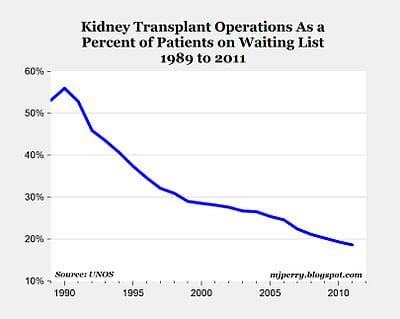

As America gets older and sicker, however, the demand for kidney transplants is exploding.

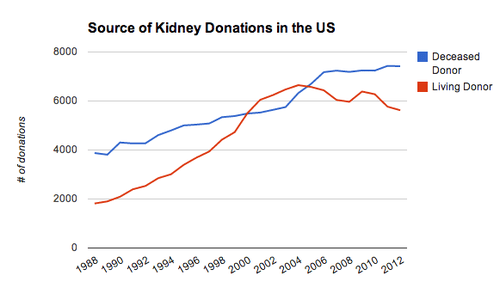

The number of kidney donations is not keeping pace. Donations today from live donors (altruistic people) or cadavers (organ donors who passed away) have barely ticked up as demand for kidneys has steadily risen. The shortage of kidneys is not a uniquely American problem. Across almost every single country, there are too few kidneys available relative to the demand.

The result is that lots of people die every year waiting for a new kidney that would save their life.

Where do Kidneys come from Today?

Kidney transplants in America are managed by the United Network for Organ Sharing (UNOS). UNOS is a non-profit with a Congressional mandate to administer the entire waitlist of patients, inventory of organs, and algorithm by which patients and donors are matched. Because of this centralized process, there is incredibly accurate information about the supply and demand for kidneys.

In the US, most kidneys come from donors that have died, as opposed to living donors that voluntarily donated their kidneys.

Most efforts to solve the kidney shortage have so far focused on increasing the supply of donated kidneys. Campaigns to sign up more people as organ donors are the most common.

Some European countries like Spain and Austria make donating organs the default – people need to choose to opt out. These countries still have much lower overall organ donation rates than the United States.

Another avenue for increasing kidney donations is focusing on live donors. One recent innovation is the concept of a “paired exchange.” Someone on the waitlist may have a family member who is willing to donate a kidney but is the wrong blood type. A paired exchange looks among a pool of families in similar circumstances to find blood type matches. If each donor has the blood type the other patient needs, then they are paired and each donor gives a kidney to the patient in the other family. Initiating these pair exchanges improves liquidity in the market for kidneys and saves lives, but it hasn’t made much of a dent on the kidney shortage so far.

Almost every country has a scarcity of kidneys despite the existence of billions of potential suppliers who could easily meet the relatively modest demand for kidneys. Every system that depends on kidney donations has failed to get enough kidneys to the people that need them.

The current system of paired exchanges and campaigns for kidney donors has noble intentions, but it’s not working. People are needlessly dying as a result.

Who Foots the Bill?

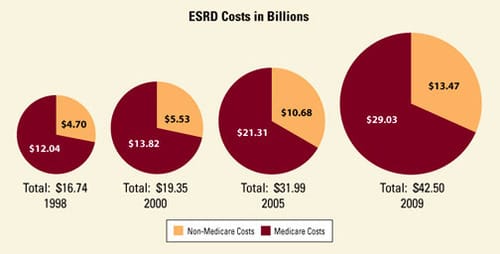

The annual cost of kidney failure in the United States is approximately $42.5 billion as of 2009. The federal government, through its Medicare program, has a special exemption that helps pays for the care of people with End State Renal Disease, even if they are not yet 65 years old. (Medicare typically only covers costs for senior citizens.) The result is that the US government pays $29 BN (68% of total kidney spending) towards covering the cost of dialysis and kidney transplants. When it comes to End State Renal Disease, the US almost has a single payer healthcare system.

As mentioned earlier, it costs approximately $75,000 per year to keep someone alive on dialysis in the United States. The vast majority of this goes to private companies that run dialysis centers or sell dialysis related equipment and drugs. Two nationwide for-profit dialysis chains, Fresenius and DaVita, provide over 60% of dialysis treatments.

A kidney transplant surgery costs approximately $105,000 in the US and is a relatively safe procedure for the donor. In most countries, it’s estimated that the surgery pays for itself within 1-3 years.

What’s Wrong with Selling Kidneys?

The idea of buying and selling kidneys have been around for a long time, but moral uneasiness has kept it from being seriously considered or implemented.

Critics of a marketplace for kidneys typical raise the following objections:

1. Kidneys would be distributed based on ability to pay, so rich people would be able to get kidneys and poor people would not.

2. If the price of organs is high, that will incentivize stealing organs. It could also motivate unscrupulous people to force other people to sell their organs in order to profit from the sale.

3. The system would exploit poor people by promising quick money for their kidneys. If someone is destitute, can they really give informed consent? While donating a kidney is relatively safe, it has inherent risks like any form of surgery.

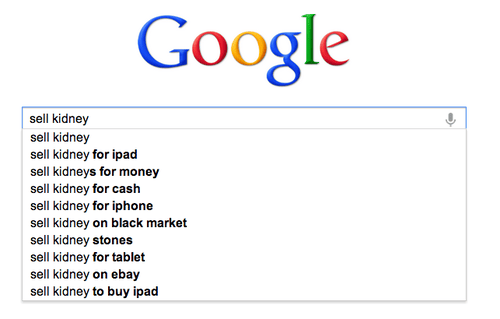

The current, donation-based system addresses all three of these concerns. The United Network for Organ Sharing distributes organs based on need, not income (Objection 1), and the price of kidneys is $0 (Objections 2 and 3). Currently, there is almost no risk of someone “selling their kidney to buy an ipad” in the United States.

If operating a free market for kidneys suddenly became legal, all of these objectionable practices might start happening. The results could be dangerous and inconsistent with mainstream American values. Wealthy people would get kidneys at the expense of poor people who might need them more. The destitute might be compelled to sell their organs for short term gain or against their will. And at a high enough price, organ theft could become prevalent.

Let’s assume we agree with all of these ethical objections. Could we devise an ethical system that pays kidney donors, saves lives, and saves money?

A Modest Proposal: Let The Government Buy Our Organs

In the United States, we already have a safe, well-organized way to get kidneys from donors to the patients that need them most. We also have one party (Medicare) that spends hundreds of thousands of dollars to keep people alive on dialysis for 3-5 years before they can get a kidney transplant. Why not let Medicare spend that money instead on buying kidneys?

If the US Government bought kidneys from healthy individuals, then the United Network for Organ Sharing could continue to allocate the kidneys on the basis of need instead of ability to pay. Instead of creating a “free market” for kidneys, the government could mandate that Medicare be the exclusive buyer of kidneys. It would create a tightly regulated system for buying up kidneys, which is better than no system at all.

What’s the advantage of letting Medicare buy kidneys instead of creating a free market? First, it would save Medicare and private insurers money since the current cost of dialysis for people on the waitlist is so high. These parties have a financial incentive to consider a plan like this.

Second, a government-regulated system can address concerns about equity. Rather than rich people privately contracting poor people to buy their kidneys, the government and the UNOS can continue to allocate purchased kidneys based on need (Objection 1). Moreover, the risk for organ thieves is eliminated in this scenario (Objection 2). Would an organ thief show up at the Medicare office with bag of kidneys? Instead, individuals would have to go through an approval process to ensure that they are not selling their organ under duress and understand the risks.

This proposal is weakest at overcoming Objection 3 – the concern that destitute people cannot give informed consent due to their financial duress. (Let’s ignore for now that we allow women to rent out their uteruses for childbirth – something more dangerous than donating a kidney that subjects the less well-off to the same risks of exploitation.)

If individuals were offered a “fair price” for their spare kidney, could you make the argument they were being taken advantage of? If the price were a million dollars? $100K? $50K? 10K? $1?

For every dangerous task, there is probably some price at which society would feel that people are being adequately compensated for the risk of performing that task. This is the case for security contractors in Iraq and surrogate mothers. Why should donating a kidney be any different?

There is some “price for a kidney” that would eliminate the waiting list, feel like a fair price, and also save Medicare lots of money. That price might be higher than what the “market price” of a kidney would be. Economists Gary Becker and Julio Elias estimate that the price of a kidney in a free market would be $15,000. It’s possible that would feel like an unfair price. Some online commentators have suggested around $50,000 as a price that they consider fair.

At $50,000, we’d consider donating a kidney. What’s the price at which you’d consider selling your extra kidney?

Conclusion

Today, there are simply too few kidneys being donated to people with kidney failure. As a result, more than 5,000 patients a year needlessly die on the waitlist in the United States. The gap between the number of people that need a kidney and the supply of donated kidneys continues to grow. Campaigns to increase voluntary kidney donations simply haven’t worked. Even dead people don’t want to donate their kidneys.

It’s time to fix this problem once and for all. Instead of hoping that more people start becoming organ donors and doubling down on failed policies, it’s time to start buying and selling kidneys.

This post was written by Rohin Dhar. Follow him on Twitter here or Google. To get occasional notifications when we write blog posts, sign up for our email list.