Here at Priceonomics, our price guides can help you learn the right price to pay for a used iPhone 4S or a used 2002 Bianchi Pista road bike. But it doesn’t look like we’ll be making price guides for digital recordings of Eric Clapton’s “Layla” or Beethoven’s Symphony No. 9 anytime soon. Last week, a New York Federal Court ruled that secondary markets for digital music violates record companies’ copyrights.

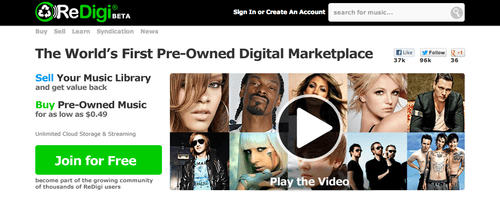

The case concerned ReDigi, a Boston-based startup building a marketplace for used digital music. Redigi buys people’s digital music collections and sells “pre-owned” tracks for as low as 49 cents. The founders believed they had done their due diligence, meeting with lawyers, ensuring that they only bought and sold tracks that had been purchased, and verifying that anyone who sold a used digital track had the file erased from their electronic devices.

Record companies sued all the same, and the judge concurred with their arguments. As reported by The New York Times:

“The case has been closely watched as a test of whether the first sale doctrine — the legal principle that someone who owns a copy of a copyrighted work, like a book or album, is free to resell it — can be applied to digital goods.

“In an order dated Saturday, Judge Richard J. Sullivan of United States District Court in Manhattan ruled that ReDigi was liable for copyright infringement, and seemed entirely unmoved by ReDigi’s arguments.”

More legal analysis of the ruling is available here.

The music industry has good reason to fear secondary markets. Unlike an iPhone or a road bike, digital tracks are mostly immune from the wear and tear that reduce their value and incite people to buy new despite the price bump.

But the music industry’s attempts to put controls on music in the digital age are what could allow secondary markets to thrive.

A major reason that people do not buy traditional products used is uncertainty. Even if the product is still in its original packaging, people fear that there is something wrong with it. This incites people to buy directly from stores.

Most any song is available for free online (if illegally). But their quality is always a bit suspect. They could contain a virus. They could be crappy quality. That’s why people still buy music from iTunes and Amazon.

To try and prevent illegal sharing, companies like Apple have controls on purchased music files that make it clear that it is an iTunes purchase and minimize how widely it can be shared. Although intended to control sharing, that control is a valuable signal of quality in a secondary market. It shows that the track was purchased, which both bosters legal arguments of resellers like ReDigi and reduces uncertainty for potential buyers – uncertainty that might otherwise send them to the iTunes store. (Otherwise why wouldn’t they just download it illegally?).

Ironically, it could be music sellers attempts to crack down on illegal sharing that makes it possible for secondary markets to thrive.

This post was written by Alex Mayyasi. Follow him on Twitter or Google Plus.