Stanford University Special Collections Archives

In 1885, former California governor and railroad magnate Leland Stanford decided it was time for a new investment. So, he ventured to Boston and asked his friend, Harvard president Charles Eliot, whether he should establish a university, a technical school, or a museum. After Eliot suggested the first option, Stanford returned to the Golden State, and with an endowment of $5 million (some $130 million in today’s dollars), founded Stanford University.

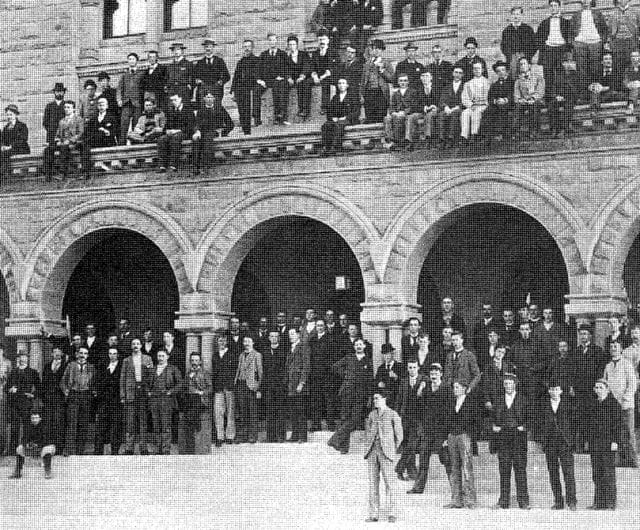

When the university’s first incoming class of 490 pupils entered its halls in 1891, hopes were high that the virtues of maturity and respectability would be upheld. “Stanford is hallowed by no traditions; it is hampered by none,” Founding President David Starr Jordan told the students. “Its finger posts all point forward.”

Unfortunately for Stanford, this often proved to be untrue in its early years: the school’s first class of men were a rowdy, playful bunch of ne’er-do-wells who left a trail of pranks in their wake.

The High Ideals of Encina Hall

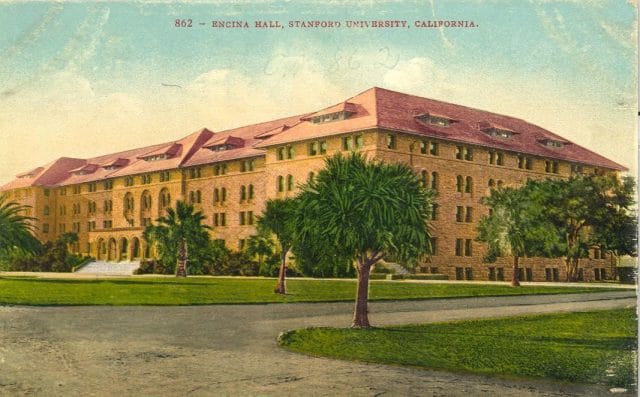

Just after founding his university, Leland Stanford set out to construct living quarters for the young men in the university’s first class. Modeled after a resort he’d come across in Frankfurt, his vision was to create a stately, beautiful building that not only inspired its inhabitants to be gentlemanly and well-behaved, but that “corresponded with his goal to establish a truly democratic institution.”

The result, Encina Hall, was a “massive, four-story, red-tile-roofed sandstone building” spanning more more 280,000 square feet. At a cost of $477,000 ($12.5 million in 2015 dollars), it was lavishly outfitted, as described in an early student’s letter home to his parents:

“The furniture in each room consists of two single iron bedsteads with bronze trimmings, either two single or one double wardrobe, a large study table, commode, mirror, two rugs, four oak chairs with high backs and a stationary washstand with hot and cold water. The rooms are all heated by steam and will be lighted by both gas and electricity…There are several large bathrooms on every floor, and electric bells and speaking tubes in all the corridors to call for anything that is wanted.”

When the university opened its doors in 1891, 300 young men — some 60% of the incoming class — were placed in Encina Hall. The 110 women in the first class were placed in a separate quarters, and the some 80 other men were left to find living quarters in cabins off-campus.

Though Stanford’s tuition was free, Encina Hall’s board, at $20 per month (roughly $530 today), was quite steep, considering that the average hourly wage in those days was 15 cents an hour. But this cost came with complete and utter freedom: operated by the Stanford Estate Business Office rather than the university, Encina Hall largely allowed for self-governance. “The institution has no rules to be broken,” wrote the university’s president, “and each student will be a free agent, taking care of his or her own conduct.”

This, it turned out, came with a long lineage of groan-inducing consequences for Stanford.

In his book “Stanford University: the First Twenty-five Years,” historian Orrin Elliott writes that these early Encina residents — mostly “high-spirited young men from the rural West” — had a complete lack of respect for university property, as well as authority of any kind:

“Encina men were proud…but this pride did not seem to include a personal feeling for the building itself. Its noble architecture, its amplitude, its great dining hall, its furnishings, were not thought of as personal possessions to be cherished and jealously cared for. Accordingly, as time went on, everything that could be abused was abused. Roughhousing spared nothing.”

At Robles Blancho Hall, where the university’s 110 female residents resided, the worst practical joke that happened was a “flower-filled urinal.” By contrast, all-male Encina Hall became known as “The Madhouse,” — a title its mischievous tenants made sure to defend that title through an endless stream of hijinks, pranks, and batshit crazy antics.

Stanford University’s First Pranksters

Once settled, the young men of Encina Hall wasted no time in making Leland Stanford’s life miserable.

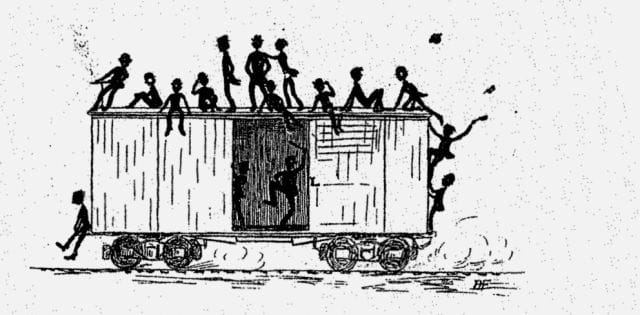

On October 17, 1891, just two weeks into the school’s inaugural year, three students — Tommy Code (Stanford’s first quarterback), Newton Booth Knox (a future mining magnate), and Tracy Russell (a future “well-known” San Francisco physician) — noticed a freight car full of “dynamos and machinery” sitting idly on a set of tracks a ways up the hill from Encina Hall. During construction of the university, the car had been used to haul materials up from the main track in what is now Palo Alto, a mile down from the road; now perched before the boys, it was nothing more than a “temptingly unguarded” opportunity to get into some mischief.

According to a 1928 account by a classmate, the boys removed the brakes and took the cart for a joy ride down to Encina Hall, where it came to a halt. Once in the vicinity, some 60 to 70 Encina youth “swarmed out to lend a hand” in pushing the cart onward, and eventually rode it all the way down to the main track. Despite their “sincerest” efforts, the car would not run back up the grade, so the students left it there, walked home, and fell asleep.

When the press got word of the prank the following morning, they had a field day mocking Leland Stanford — a railroad tycoon — for his lack of oversight. As written in an Oakland Weekly Journal article, Stanford was furious:

“When the philanthropic founder of the University found out, he is said to have used language not used in the Palo Alto textbooks, and to have furthermore jumped stiff-legged and declared the whole school of boys should be sent home. It was hours before he could see it was only a case of ‘boys will be boys’…and he promised that the students would thereafter only study railroading theoretically.”

A special locomotive had to be called in from San Jose to push the car back up the grade.

***

Several years later, in 1894, it was announced that ex-U.S. President Benjamin Harrison would be coming to Stanford University to teach a single course on constitutional law. For his time, he’d be compensated $10,000 — a hefty sum, but, in the eyes of the young university, well-worth the “prestige and credibility” his post would signify.

Originally, Harrison was to stay in Leland Stanford’s private residence, but Stanford ended up passing away just before his arrival, and the President was relocated to a lavish guest suite in — of all places — Encina Hall. To accommodate Harrison, Mrs. Stanford sent over “a quantity of liquor, wine, and fine cigars” for his enjoyment.

Over the course of the next ten weeks, the President instructed his students on the “rights and duties of good citizenship,” then he headed back to the East Coast. As soon as he departed, a few informed students snuck into the suite, made off with the wine, liquor, and cigars, and “proceeded to share them with a congenial group of hall men.”

A campus flier for President Harrison’s welcoming concert

Stanford administrators were, of course, infuriated that the students tampered with the President’s liquor supply — but they were so humiliated over the incident that they chose to keep the investigation internal and under wraps.

When the university failed to identify the culprits, its business affairs branch resolved to charge the entirety of the goods — some $33.80 — to the general population of Encina Hall, who swiftly tipped off the local papers. As The Palo Alto Daily later recounted, this fee didn’t go over too well with the Hall’s rebellious occupants:

“Vigorous objection was made, and, at a meeting called to talk things over, budding student lawyers argued that, as the presence of the wine and tobacco in the Hall was forbidden, the articles were contraband and the authorities could have no recourse.”

Eventually, the parties settled on a fine of $28.55 — but the prank’s effects were far from over.

When the press (including William Randolph Hearst Jr.’s sensationalist San Francisco Examiner) got ahold of the story, it blew the details out of proportion, pegging Harrison as an alcoholic derelict, and the university’s officials as corrupt rule breakers. Writes historian Howard Bromberg, “Reverberations of these fantastic tales echoed in the press for many years, to the embarrassment of all concerned.”

Ironically, the students who’d orchestrated the prank were excluded from the denigration. Though the true culprits were never identified, 34 years later, an Encina Hall resident claimed that two students were to blame: Tommy Code (who’d also been the perpetrator of the freight car prank), and a serial loafer named Milton Grosh. Both, testified the source, were members of the Stanford football team that had defeated Cal 14-10 in the first ever Big Game — and both were apparently also notorious for their shenanigans in Encina Hall.

***

In the ensuing years, as well as those between the aforementioned pranks, Encina Hall earned a legendary status on campus for its ridiculous antics — most of which were entirely unimpressive.

Students took great joy in “turning up” rooms (i.e. flipping every piece of furniture upside down), throwing boxes filled with water on unsuspecting passersby, and switching out broken chairs for functional ones, “making it dangerous for visitors to take a seat.”

Oftentimes, pranksters had a flagrant disregard for the well-being of their superiors. In a letter home to his parents, a one freshman joyfully recalled almost knocking out one of his professors in the hallway:

“At 11:30 P.M. the lights went out, and the fellows ‘fired’ a chair, a spittoon, and several other things down the stairs…the chair came pretty near hitting Professor Swain on the head as he walked by.”

“Last night I was laying for a man to come out of the bathroom,” bragged another student in an archived text. “When he came, I banged him with the pillow and it turned out to be a professor who lives on that floor.”

A group of Encina Hall men with their velocipedes (c. 1895)

By 1896, things had gotten so out of hand that the city office had to intervene and hire a night watchman — “a stalwart ex-policeman with plenty of courage, and little discretion” — to patrol Encina Hall. “His habit of flourishing a revolver, of making himself at home in the club room, and of entering student’s rooms without knocking was bitterly resented,” wrote one historian — and eventually, his presence ignited a violent student backlash.

In a report written by Stanford’s business manager, Charles Lathrop, Encina Hall’s residents were made to sound more like violent rioters than university students:

“C.S. Thompson, room 130, shot his revolver twenty-five times last night in the Hall and out of the window, liable to kill anyone passing in front of the Hall at that time…the way he carried on was outrageous. W.S. Fay, room 119, flooded the place with water, shot fire crackers, and broke electric lights…There is no use talking to these men as it will do no good. They are the two worst men in this hall.”

Finally, tensions mounted so high that the residents of the Hall actually did organize a riot, with the intent of dispatching the watchman. Historian Orrin Elliott recounts:

“It began early in the evening when a group of students turned out the lights in the Club Room, overturned tables, and tossed chairs about the room, apparently in order to create a disturbance that would attract the attention of the watchman. When the latter entered the room, the students generally withdrew and gathered on the third or fourth floor landings. The appearance of the watchman at the door of the Club Room was the signal for a fusillade which, with the accompanying noise and yelling, lasted a couple of hours. Cuspidors filled with water were thrown down, followed by boards, boxes, bottles filled with water, and whatever else came handy. Fortunately no one was hurt, and the property damage was not much greater than an ordinary riot.”

The 20 men deemed responsible were identified and removed permanently from the hall.

Gradually, the Encina residents began to realize that they posed a risk to themselves — but even then, they were only concerned about their own culpability. “While I do not wish to be an alarmist, I think it is not impossible that some tragedy may occur there,” wrote one student, in 1905. “It is at least within the range of possibility that someone may be seriously injured or even killed in these affairs, and if so, there is no way by which we can escape moral responsibility.”

Stanford’s campus after the 1906 earthquake

It would take the natural wrath of Mother Nature to quell Encina’s reckless youth: in the early hours of April 18, 1906, a 7.8 magnitude earthquake rippled through the Bay Area, destroying 80% of San Francisco. For Encina Hall, the damages were comparatively moderate — two collapsed chimneys, and some structural cracks — but it was enough to force an evacuation of the building. For a brief moment in time, hooliganism took a hiatus.

In retrospect, writes one historian, the disaster did much to clear the air of hostility between the university and Encina’s ne’er do wells:

“Happily the earthquake…did something to clear the local atmosphere. The large aspects of the University life resumed their proper place. In the presence of the great disaster there was a disposition to let bygones be bygones and to find a reasonable basis for faculty-student relations in the matter of conduct and discipline.”

Aside from the occasional “beer bust” or hurled chair, conduct in the Hall generally improved over the ensuing years. Encina’s “bad boys” went on to become lawyers, physicians, diplomats, and even U.S. Presidents (Herbert Hoover was among the hall’s residents) — and all was written off as a footnote in Stanford’s archives.*

*Note: By the 1950s, Encina was taken over by administrative offices, and no longer housed students. Years later, in 1972, a huge fire destroyed most of the hall, and after extensive renovations throughout the 1990s, it was made into a state-of-the-art conference center.

This post was written by Zachary Crockett. You can follow him on Twitter here.

To get occasional notifications when we write blog posts, please sign up for our email list.