Image source: “Brokers with Hands on Their Faces” Blog

Whenever there is a downturn in financial markets, the press loves to publish pictures of Wall Street traders looking dejecting and palming their face. This occurrence is so common it has its own meme– “Brokers with Hands on Their Faces.”

The economics of Wall Street stress is simple: if you’re losing big money, you’re probably down in the dumps. But recent research by neurobiologist John Coates suggests that there is a biological reason for all this facepalming.

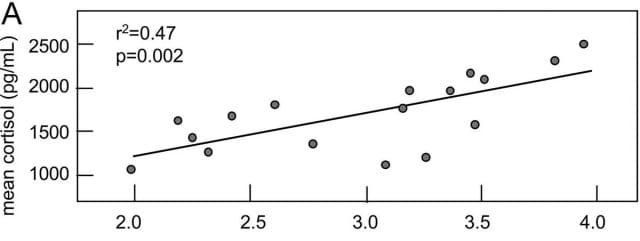

In a study of London securities traders, Coates and his team took daily measurements of traders’ hormone levels. They discovered that a trader’s cortisol levels were higher on days when his earnings deviated from what he expected:

Cortisol Levels When Profits/Losses Deviate from the Mean

Source: PNAS

Cortisol usually isn’t a problem– it “mobilizes nutrients into your bloodstream, rapidly increases its levels of glucose, providing muscles with a burst of energy, (and) it shuts down all non-essential bodily processes.” And it can power us through stressful job interviews, product deadlines, and big presentations.

But in times of sustained market volatility (such as during a recession), researchers found that the cortisol levels of traders remain elevated for long periods of time. This is problematic because sustained levels of high cortisol promote anxiety, intense aversion to risk, and a selective recall of negative events. So when the market looks bleak and the future is uncertain on the trading floor, some traders crumble under the stress load. When distressed stocks actually need the risk-taking appetite of traders, shellshocked traders are no longer hungry. Coates likens this condition to:

“the state of ‘learned helplessness’ identified in the 1960s by Martin Seligman, a psychologist who delivered random electric shocks to dogs constrained in harnesses. Eventually the animals lost the will to escape, even once they could do so.”

So while traders might be taking too many risks in a booming market, they might not be taking enough during a crisis. And due to the effects of sustained stress, cortisol is likely to “rise in a market crash and, by increasing risk aversion, to exaggerate the market’s downward movement.”

Which inevitably leads to more facepalms.

To get occasional notifications when we write blog posts, sign up for our email list.