![]()

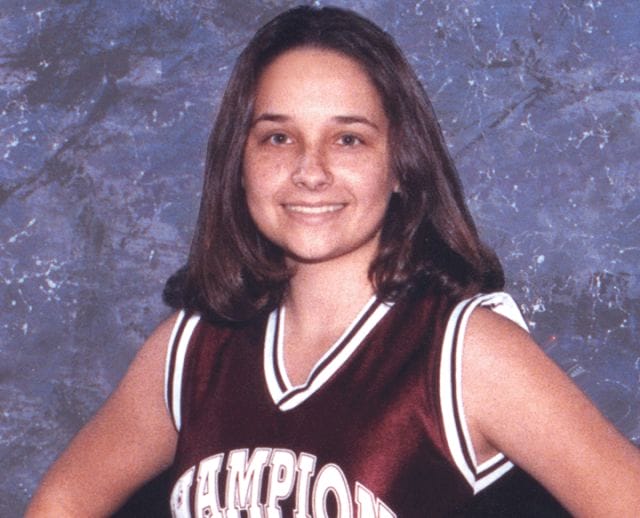

On the evening of January 22, 2002, somewhere in the suburbs of Chico, California, 15-year-old Kristie Priano loaded into the back of the family minivan with her brother and parents. An honor roll student and high school basketball standout, she was to start in a game that night.

Around the same time, across town, another teenage girl had just stolen her mother’s Toyota Rav4 to go for a joy ride. Informed of the theft, the local police dispatched several officers to follow the vehicle through residential streets. Initially, the car in pursuit was driving relatively slow — 30 to 35 MPH, according to a police report. But when the police car switched on its lights and siren and picked up speed, the “suspect” panicked and floored the gas pedal.

A frantic, albeit brief, police chase ensued: with poor visibility, officers tailed the teen at approximately 65 MPH, blazing through four stop signs and multiple four-way intersections.

Several minutes into the pursuit, the joyrider spotted a minivan in her path — but it was too late to attempt a stop. With crushing force, she slammed into the back driver’s side of the Priano family’s car, directly where Kristie was sitting. Suffering from massive head trauma, Kristie fell into a coma and passed away six days later.

***

This story — a high-speed police chase leading to the death of an innocent bystander — is one of hundreds that play out every year in the United States. In the vast majority of these chases, officers aren’t pursuing a murderer, child abductor, or vicious criminal; most of the time, the offenders have committed nonviolent crimes that don’t warrant exposing the public to the immense risk of a chase. Though efforts have been made to mitigate these risks through restrictive policies, officers still largely retain the individual agency to initiate chases: hopped up on adrenaline, they often choose to pursue.

But given the risks, and with new tracking technologies available, are high-speed police chases really worth the risk they pose to the public?

The Toll of Police Chases

High-speed police chase data, like most police data, faces a dilemma: while individual departments collect figures and numbers, they are not mandated to report them to any state or federal agency. As such, no comprehensive historical repository of high-speed police chases exists.

The most accurate figures that can be found come from the National Highway Traffic Safety Administration (NHTSA), which tracks all reported vehicular accidents in the U.S. In 1982, amid mounting concerns about fatal police pursuit crashes, NHTSA launched the Fatality Analysis Reporting System (FARS), a national database which tracks, among other incidents, deaths resulting from high-speed police chases.

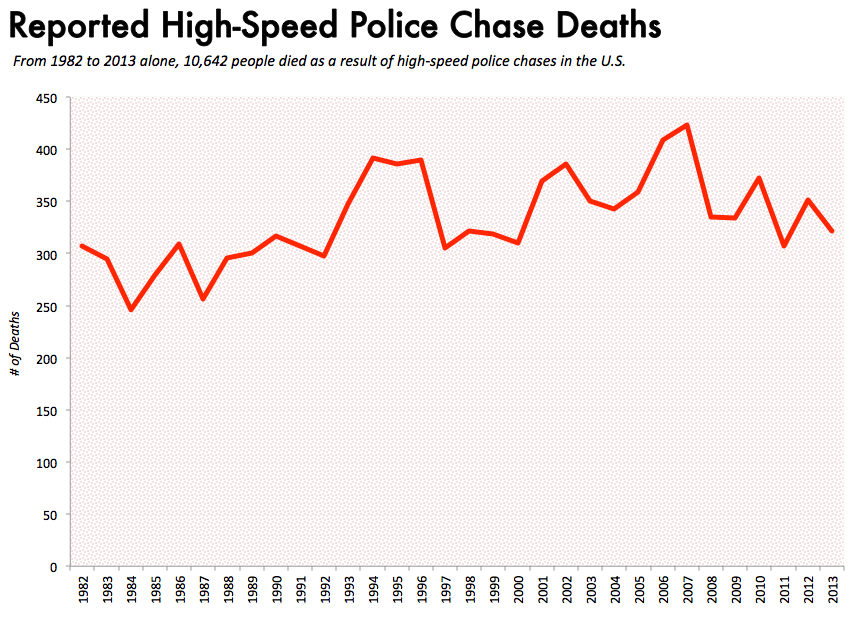

According to their data, 10,642 people have been killed in these chases over the past 32 years — some 332 deaths each year.

Zachary Crockett; data via the National Highway Traffic Safety Administration’s FARS database

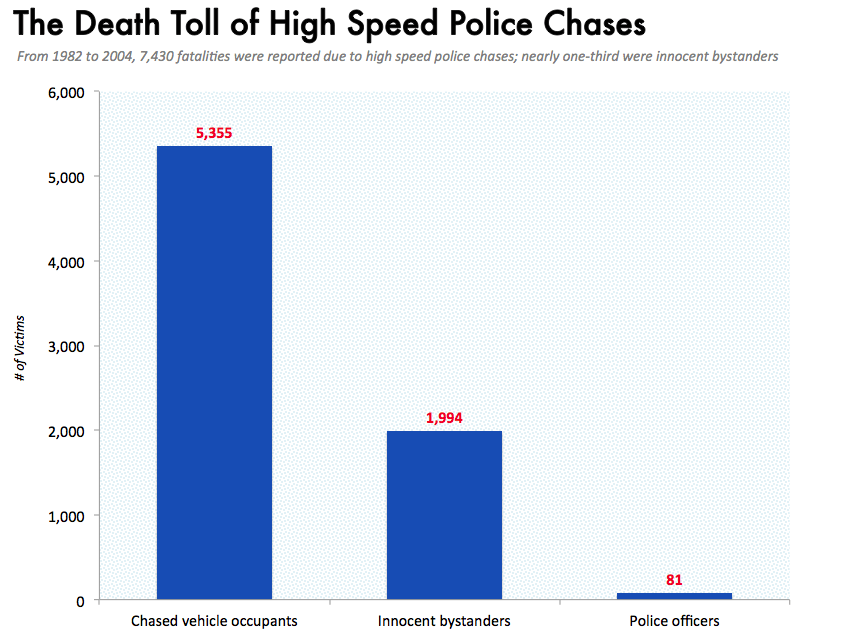

In 2004, researchers analyzed 7,430 of these deaths, and published a disturbing revelation: while the majority of those killed are occupants in the chased vehicles, innocent bystanders make up nearly one third of all deaths resulting from high-speed police chases. The police officers who initiate these chases make up less than 1% of all fatalities:

Zachary Crockett; data via the National Highway Traffic Safety Administration’s FARS database, and Prehospital Emergency Care (Hutson, 2007)

Not surprisingly, alcohol was determined to be involved in roughly 62% of all fatal crashes involving chased vehicle suspects. Astonishingly though, alcohol was also present in 25% of reported police fatalities: 20 of 81 officers killed in pursuit had a BAC above the legal limit of 0.08%.

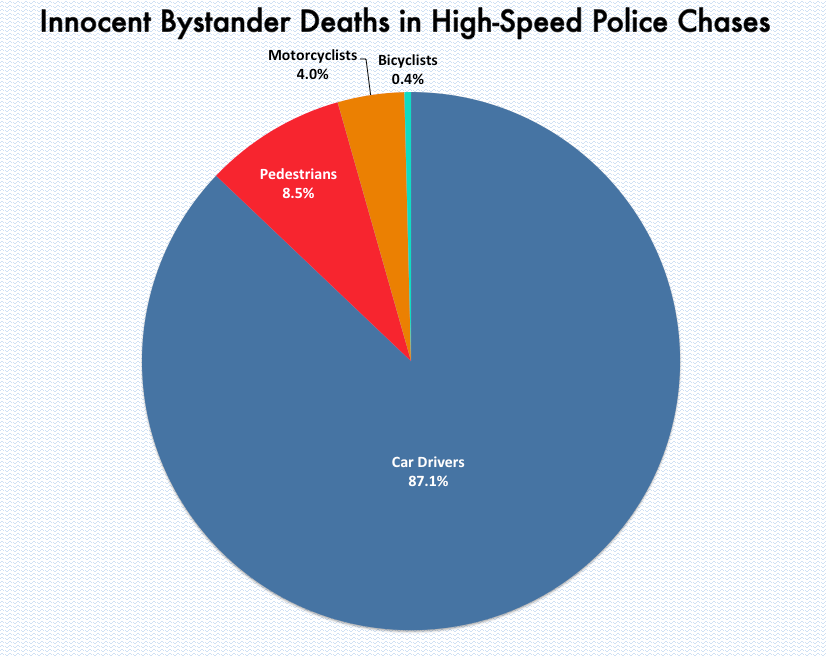

And what of the innocent bystanders killed? The vast majority of them are drivers on the road who are hit either by the police car or the vehicle being pursued. In addition to innocent drivers, roughly 30 pedestrians and cyclists per year are killed as a result of pursuits:

Zachary Crockett; data via the National Highway Traffic Safety Administration’s FARS database, and Prehospital Emergency Care (Hutson, 2007)

Because chase data is submitted on a voluntary basis by police departments, these figures are vastly underreported. This absence of mandatory reporting also leaves us with only a vague idea of the total number of police chases that occur each year. The most widely-accepted estimate — 30,000 to 40,000 — comes from a 2002 FBI report which reported that 1 out of every 100 police pursuits ends in death.

Still, based on the crash data that does exist, the anatomy of a typical high-speed police pursuit can be delineated:

1. Pursuits typically last between 1-5 minutes, with the vast majority of crashes occurring within the first two minutes of the chase.

2. Roughly 40% of all car pursuits end in a crash, 80% of which are with another vehicle. Of these, 20% result in traumatic injury, and 1% result in death.

3. Innocent bystanders (uninvolved drivers, pedestrians, and cyclists) account for nearly one-third of these deaths.

Clearly, high-speed pursuits put innocent civilians at great risk. Given this, one would think that police officers only initiate chases in dire circumstances. Unfortunately, this is not the case.

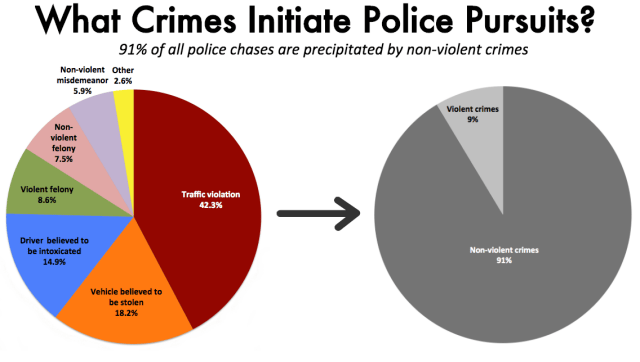

Zachary Crockett; data via the International Association of Chiefs of Police

An analysis done by the International Association of Chiefs of Police, in conjunction with the National Institute of Justice, revealed that 91% of all reported police chases are initiated over non-violent crimes. Simple traffic violations (e.g. rolling a stop sign, or driving with a busted taillight) account for nearly half of these.

Given the relatively low danger risk most of these crimes pose, are high-speed police chases — which endanger the safety of the public, and cause hundreds of deaths per year — really warranted?

Proposing a Policy Change

Following Kristie’s death in 2002, her mother, Candy Priano, founded PursuitSAFETY, a national nonprofit bent on reducing the deaths and injuries resulting from pursuits.

Esther Seoanes, whose husband was also killed during a 2012 police chase, is one of PursuitSAFETY’s executive directors. She tells us that the organization aims to reduce chase fatalities by limiting police policy to violent felony offender chases only — or, as she iterates, “when the need to immediately apprehend a suspect is so great as to outweigh the inherent dangers of the pursuit.” They also call for data reporting on such incidents to be mandatory, and for police forces to go through more rigorous pursuit training.

These attempts are not met without criticism. Pro-chasers argue that when police stations limit their officers’ ability to pursue offenders, it sends the message that bad guys can take advantage of that fact (“If law enforcement is defanged,” one critic tells us, “it’s going to be difficult for them to protect the community”). Empirical research seems to work against this idea: studies of multiple departments have shown that after a policy change, there is no discernable change in criminal activity.

Dr. Geoffrey Alpert knows this better than anyone. As a professor in the University of South Carolina’s criminology department, he has been conducting research on high-risk police activities for nearly 30 years, and over the time span, he’s become a nationally recognized voice on the topic of pursuits.

In a brief for the National Institute of Justice, he reviewed the practices of more than 400 law enforcement agencies, and found that 91% of them had some form of high-speed pursuit policy, most of which were implemented in the 1970s. About half of these agencies reported updating their policy in the last two years to be more restrictive. However, in most cases, there is no governing process: even with restrictive policies, officers at many branches generally have free reign to pursue whomever they please.

In an anonymous op-ed piece, one officer explains the the attitude that pervades many stations:

“Pursuits are an intricate part of the predominantly male culture of young police, particularly in inner-city areas and the highway patrol. They invariably become a pissing competition between the police and the crooks to see who is a better driver. When that dangerous mix of testosterone and adrenaline kicks in, all reason goes out the window…I know police who spend their lives trying to get into pursuits because it is such an adrenaline boost.”

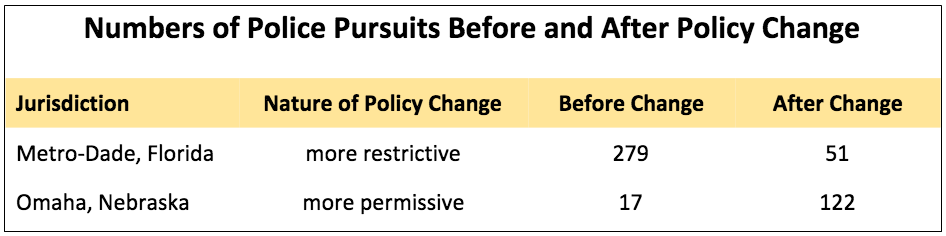

This said, Alpert did find some favorable results from stations adapting more restrictive chase policies — most notably, in Florida’s Metro-Dade County. But other departments in the U.S., like that of Omaha, Nebraska, have negated this success by turning to more permissive policies:

Via Police Pursuit: Policies and Training (National Institute of Justice, Dr. Geoffrey Alpert)

Through his research, Alpert has come to an ultimate conclusion: “The need to apprehend someone for a traffic offense or a minor crime is not worth the risk of death or injury,” he says. “Anything that’s not a violent crime simply shouldn’t be chased.”

The Promising Rise of Tracking Technology

Police departments have long-since integrated technology into the pursuit process: first with spike strips, and later with helicopters and license plate tracking software. Traditionally though, these technologies haven’t served as alternatives to chases, but rather as supplemental components.

Tracking technology company StarChase thinks they’ve found a different solution — one that could substantially decrease instances of pursuits and the resulting deaths of innocent bystanders. The answer? GPS “bullets.”

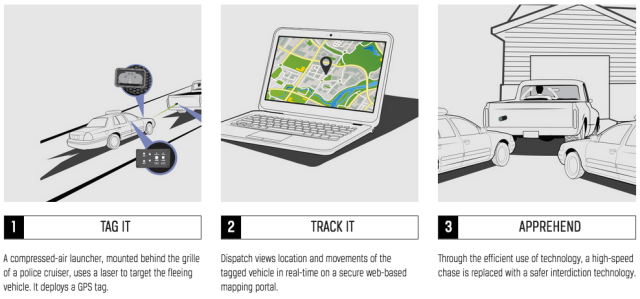

Trevor Fischbach, the company’s founder and CEO, explained to us how the system works:

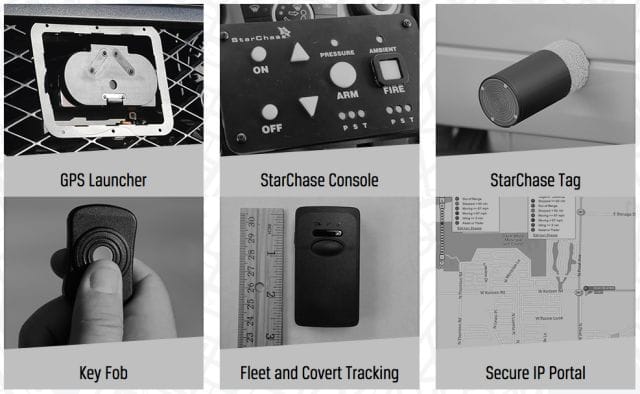

“Basically, a launcher equipped with GPS trackers is attached to the patrol car’s grille. It can be controlled either by a panel inside the car, or a remote device…when it’s deployed, the tracker sticks to the suspect’s car, and tracks, in a real-time secure mapping system, the coordinates of the vehicle. This data can be accessed from dispatch, the patrol car, or a handheld device.”

The “bullets,” roughly the size of soup cans, are fitted with a strong adhesive to ensure that they stay put, and must be fired from within 20 feet (or two cars’ length) of the targeted vehicle. StarChase’s web-based software keeps tabs on a tracked vehicle for up to 10 hours.

Components of the StarChase’s Pursuit Management Technology; via StarChase

In an ideal situation, the tracker is fired, and the officer then calls off his pursuit. Data has shown that within 90 seconds of realizing he is no longer being pursued, a suspect returns to driving safely, so as not to stand out. Once the risk of a crash is mitigated, police officers can choose the appropriate moment to track down and apprehend a criminal.

So far, Fischbach says StarChase has been integrated by 20 police agencies across America; in addition, the Department of Justice is pushing it as an alternative to high-speed pursuits. At $5,000 per unit, installation is not cheap, and given departments’ tight budgets, has likely hindered it from being more widely adopted.

A 2014 report on StarChase’s effectiveness (coincidentally written by Dr. Alpert, the police chase expert we mentioned previously) found that, based on 25 deployments of StarChase’s GPS units, there was a 55% success rate (that is, the tags stuck to the car, and an arrest was later made). But StarChase representatives tell us that number is closer to 85% now.

“It’s a wonderful technology,” says Alpert, “but it’s like everything else: we have so many ways to reduce the number of pursuits, yet we don’t fully integrate them.”

Ultimately, the solution to minimizing police pursuit deaths is not singular. Likely, it lies not only in technology, but in a combined, increased effort to collect more accurate data and more strictly enforce pursuit policies.

Kristie Priano, a 15 year-old teen who was killed during a 2002 police chase; via Kristieslaw

Every year in the United States, some 332 people — one-third of whom are innocent bystanders — die as a product of high-speed police pursuits. By contrast, the FBI reports that the police commit 400 “justifiable” homicides annually. Due to a lack of police data, both tallies are, almost certainly, severely under-reported.

While police violence has recently (and rightly) been in the media spotlight, deaths caused by police pursuits continue to remain something of an underground epidemic, fought against only by a handful of justice crusaders.

Contrarily, police chases are lionized in America, and capitalized on for their shock value. Television shows like Cops and World’s Wildest Police Videos make light of the pursuits by dubbing them over with “feel-good” commentary. YouTube teems with tens of thousands of chase videos, which cumulatively have several billion views. News stations have oft-reported quadrupling their ratings while airing them on live television.

As Nancy Valenta, news director of Los Angeles’ Channel 4, told a reporter in 1992: “Any time you have a car driving down the highway at excessive speeds, endangering the lives of other drivers, perhaps armed, that’s a story and we are going to cover it.”

For the families of those killed in unnecessary police pursuits, the story isn’t as thrilling.

![]()

This post was written by Zachary Crockett. You can follow him on Twitter here.

To get occasional notifications when we write blog posts, please sign up for our email list.