When Matthew Manos was 16-years-old, he decided he wanted to be a designer.

So, he did what any aspiring teen entrepreneur would do: he bought a Mac. Then, he enrolled in a digital art class and spent long nights learning Photoshop, Illustrator, and InDesign. He began with the usual stuff – like rendering his friends’ faces onto cats – but soon craved more fulfilling work. A few months later, while hanging out at his local skatepark in Sunnyvale, California, an opportunity arose.

“Down in the bowl, this guy was doing flips in his wheelchair,” Manos recalls. “I was super interested – I had to meet him.”

As Manos approached, he realized the man wasn’t alone: a small group of children in wheelchairs followed him through the park, grinding down pipes, flying down slopes, and swiveling with reckless abandon. The man, it turns out, was running a non-profit – then known as Wheelchair Skater – that encouraged disabled children to participate in extreme sports. After speaking with him, Manos offered to make promotional stickers for the non-profit.

It was his first design project, and he did it for free.

“To be honest,” says Manos, “I never imagined how pivotal a moment the creation of those silly stickers would have on my life at the time.”

Today – a decade later – Manos is the founder and managing partner at verynice, a design firm that gives 50% of its work away for free to nonprofits like Unicef, Human Rights Campaign, and 826 Los Angeles. verynice has built a team of 350 volunteers and contractors that has saved not-for-profit organizations in 45 countries over $2 million in design services.

And perhaps most importantly, he’s mapped out his entire business model so that others may follow suit.

Uninspired Beginnings

Matt Manos is happiest when his design work is used for the common good

While pursuing his undergraduate degree in design from UCLA, Manos says he was indoctrinated with industry stereotypes: designers don’t start businesses – they brand businesses; they don’t create products – they package ideas; they don’t build communities – they design housing.

He was told that this system was inherently static: it was a business’s role to make money, and businesses employed the designer solely to help sell its products. For years, Manos had known that he wanted to start a business, but as he was exposed to the “reality” of the design landscape, he grew skeptical.

For some time, he steeped himself in the theory of social design, which posits that a designer has a “responsibility to bring about social change.” But as he researched, he found that while most “social” design firms claimed to work toward benevolent causes, they still charged non-profits substantially for contracted work:

“I learned that nonprofits in the U.S. alone spend $7.6 billion on marketing and design every year,” he recalls. “And I thought: why not provide nonprofits with free design work so they can directly reinvest that money toward their causes?”

“A nonprofit’s mission is not to have beautiful website – it’s to save the world, to do noteworthy things,” he adds. “It shouldn’t be spending money on things not tied to its mission.”

With many questions, he set out to address these issues.

Step 1: Work Really Damn Hard

A recreation of Manos’s napkin

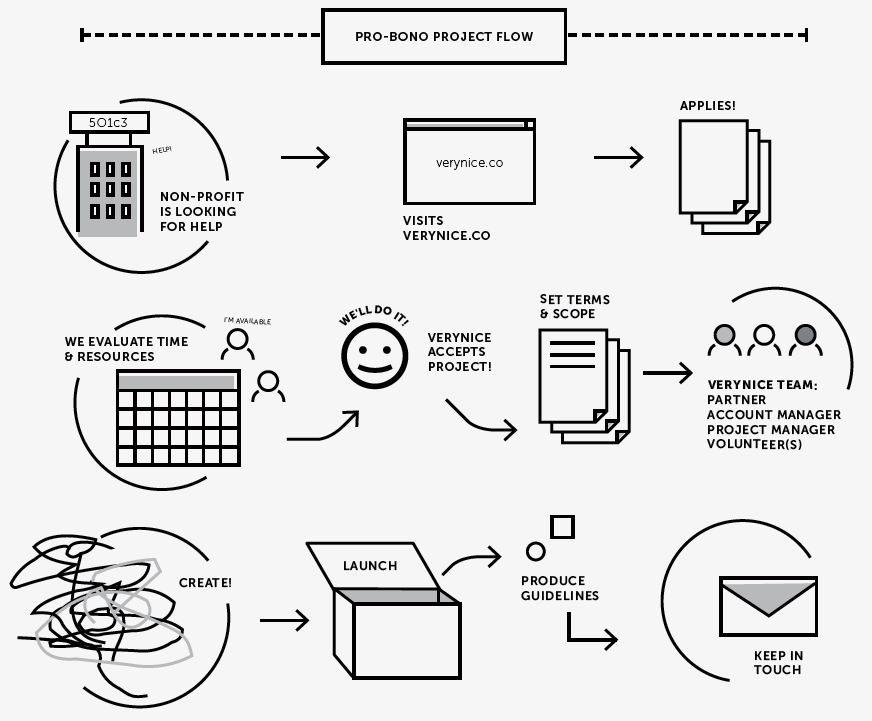

In 2008, during his last years of college, Manos set out to offer his design services at 100% pro-bono rates to nonprofits. He launched his own company, verynice, and “naively” scrawled his early working company motto on a dinner napkin: “Save the World.” (This would later morph into “Change the design industry through disruptive innovation and authentic intention”).

He spent his nights, weekends, and virtually all of his free time providing work for his clients at no cost – simply for the joy of making a positive difference. He had no employees, managed all of the work himself, and thoroughly enjoyed himself while doing it – though the initial jobs were “small and irregular.”

A year later, the summer after he graduated from UCLA, Manos had his first “big break”: he won a bid to design the promotional materials for MTV’s horror film, Savage County. The big-name boosted his credibility substantially, and work for both nonprofits (pro-bono) and small businesses (paid) trickled in.

When Manos began his MFA program that fall, he faced the precarious challenge of balancing coursework and running his business full-time. “It was absolutely horrible,” he laughs. “I’d get to school at 4 AM, work on my company until 10 AM, then do school stuff the rest of day until 5 or 6 PM.”

All the while, he began to develop a more focused business model.

Though Manos enjoyed his nonprofit work, a 100% pro-bono design company would not work. But he also didn’t want to create a company that mostly did paid work for corporations just like everyone else. Ultimately, he settled on a middle ground: he’d run verynice as a for-profit corporation that donated 50% of its work for free to nonprofits.

***

The concept of giving away free stuff is nothing new, admits Manos. In the 1880s, Coca-Cola offered the first coupon, which promised a free glass of soda. Within 10 years, one in nine Americans had consumed the beverage, largely thanks to the company’s promotional giveaways. Consumers in the 1950s were inundated with “buy one, get one free campaigns” from nearly every competing brand. In the last few decades, businesses like Tom’s Shoes have given this model a philanthropic twist by donating one product to a child in need for each product purchased.

These concepts, however, were rarely applied to the service industry, where the cost is not simply rooted in manufacturing, but involves employees’ time. When Manos first proposed his idea of giving away 50% of his design work, others scoffed at it. “A lot of influential people told me it was a bad idea,” he says. “They’d tell me, ‘Don’t give work away for free – it devalues your design, and it’s hurting the economy by taking jobs away!’”

For Manos, it was a “moral, ethical decision” – something he felt was his duty as a designer. But a glaring question remained: how could he afford to give away his work for free?

A verynice Business Model

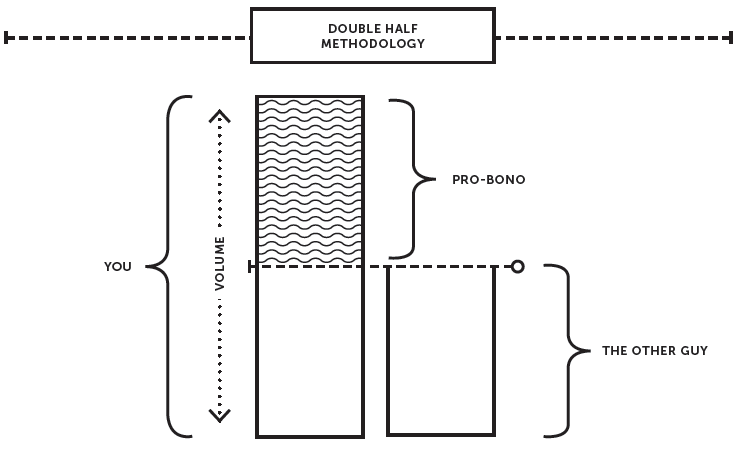

After much thought, Manos had an answer: “if you want to give half your work away for free and do just as well as the next guy, the simple equation is that you have to do twice the amount of work that they do.”

In other words, he’d do twice as much paid work in order to devote 50% of his work to nonprofits at no cost. Manos calls this the “double-half” methodology:

In order to make this model work, Manos needed to build out “an innovative approach to capacity building.” He knew he’d have to get creative with outsourcing work and that he’d have to build a large network of remote contractors and volunteers keen on providing their services for free to nonprofits.

The process proved to be surprisingly organic. “As soon as we launched our website, we got our first volunteer, a designer based in D.C.,” Manos says. “What made it special is that she just approached us without us even posting a listing.” Ironically, adds Manos, this differed greatly from the “volunteer canvassing” and guilt-tripping utilized by most of the nonprofits he hoped to help.

As Manos signed on notable organizations like Amnesty International and the United Nations, his pool of volunteer applicants, hungry for exposure and experience, grew tremendously. By the end of 2012, he had a remote team of over 100 contributors – almost all of whom did both pro-bono work for nonprofits and paid work for for-profit companies with verynice.

“Our volunteers make a social difference, and have the opportunity to gain valuable experience” says Manos. “What’s more, when you do something for free, you have more creative control over your vision – it allows for the piloting of experimental ideas.”

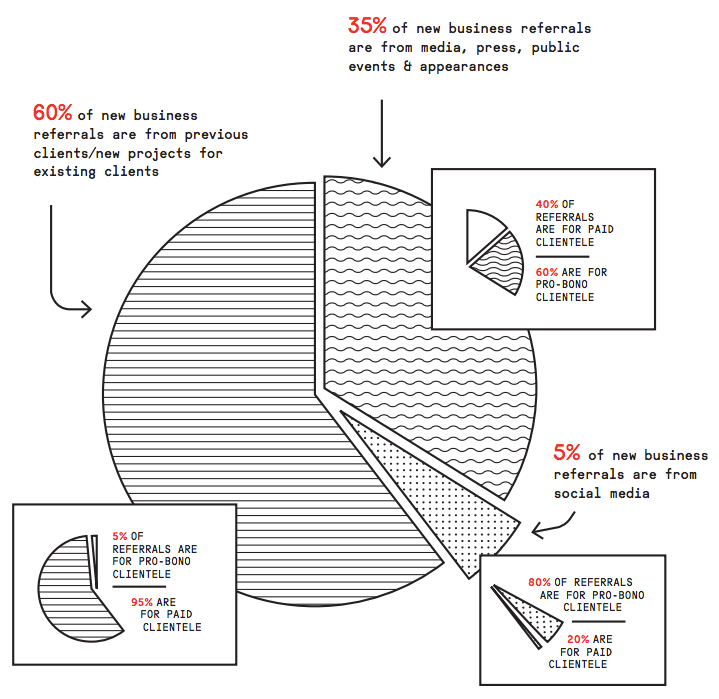

The influx in nonprofit work also made verynice visible to for-profit companies willing to pay for great design work, says Manos:

“We were working with a nonprofit in Orange County (CA) for long time…and in the course of things, we spent a lot of time with their Board of Directors – one of whom was involved at Disney. He got to see what we were capable of through the whole process, and when a project popped up at Disney, we were the first company he thought of, and we were hired for the job.”

Disney wasn’t a unique case: the boards of most large nonprofits teem with CEOs of massive for-profit corporations, so verynice can often segue into paid work though these connections. Nonprofits also tend to have hundreds of volunteers with day jobs, adds Manos, and they often set verynice up with paid work too.

Today, verynice’s revenue streams look something like this:

Fifty percent of the company’s clientele is composed of 501(c)(3) nonprofit organizations, and 50% is paid work (25% startups and small businesses, 20% for-profit social enterprises, and 5% Fortune 500 companies).

What started as an “impractical idea” solely operated by Manos has since grown into a staff of almost 20 – two business partners, a few managers, a few strategists, and a half-dozen vetted designers – all of whom oversee the work of 350+ volunteers and contractors around the world. The company has offices in Los Angeles, New York, and Austin.

verynice’s Los Angeles office

And verynice isn’t just a company – it’s an ideology, a movement.

In October of 2013, Manos crowdfunded $10,000 to produce How to Give Half Your Work Away for Free, a book scrupulously breaking down the company’s business model. A second version of his book, published just a few weeks ago and available for free online, has garnered attention from not just designers, but a wide array of business owners around the world wishing to integrate his philosophy.

Manos has lofty goals for the future. For one, he’d like to hit $10 million in pro-bono work by 2020 (verynice has currently given away about $2 million worth in services). Even more importantly, he’d like to scale the model he’s created and provide small businesses with the means to replicate it.

“A lot of design firms optimize business to make as much money as possible,” he says. “Obviously, making money isn’t a bad thing – but what ultimately matters is the legacy our businesses leave behind.”

![]()

This post was written by Zachary Crockett. You can follow him on Twitter here.

To get occasional notifications when we write blog posts, please sign up for our email list.

To learn more about Matt and verynice, check out his awesome book, How to Give Half of Your Work Away for Free.