Ten million Americans can recall where they were the night of September 29th, 2013. They were watching the series finale of Breaking Bad. And they were watching it on AMC, a cable channel that once cut its teeth airing reruns of black-and-white movies.

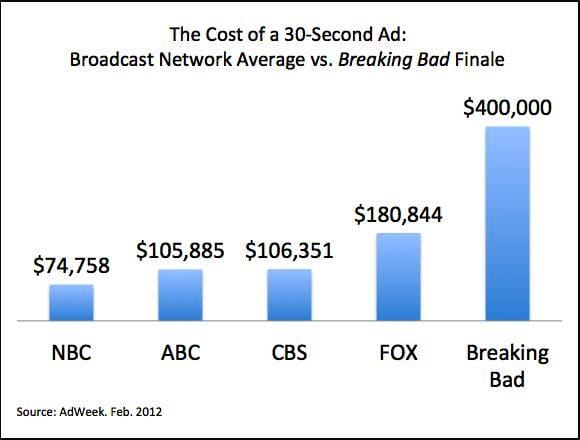

The suits at the network were prepared. Like Walter White, the show’s ruthlessly efficient meth dealer, they knew they had a quality product on their hands. And they charged their customers accordingly. AMC extended the runtime of the last two episodes from 44 to 54 minutes – 75 minutes apiece with commercials – and raised its advertising rates to as much as $400,000 per 30-second spot. The 21 minutes of commercial airtime in “Felina,” the show’s final episode, may have earned the network $7-8 million in advertising revenue.

But keeping Breaking Bad on the air was a big investment. Shooting the show cost about $3 million per episode in 2010, and $3.5 million per episode in its final season. The show’s last 16 episodes cost approximately $56 million to produce.

And finding a hit like Breaking Bad – or even finding a viable show to put on the air in the first place – often costs networks hundreds of millions of dollars each year in development costs and pricey, failed pilot projects.

Things could get even more expensive. Breaking Bad uberfan Jeffrey Katzenberg, co-founder of Dreamworks, reportedly offered to pay $25 million per episode to produce three more episodes. That’s a total of $75 million, at an average of $568,000 per minute of final air length.

This is just the tip of the iceberg. AMC catapulted itself from backwater cable channel to Emmy-winning network in just a few years – and now everyone wants in on the action. Netflix paid $100 million up-front for two 13-episode seasons of its original series House of Cards, and CEO Reed Hastings has stated his intention to create at least five more originals per year at similar budgets.

Microsoft recently opened an original content business under CBS veteran Nancy Tellem. CAA, Hollywood’s leading talent and literary agency, expects Microsoft to compete with Netflix on a similar pricing structure.

Few industries would routinely pay millions per unit of an item, sight unseen, with minimal (and sometimes no) market research. So how can the TV business afford to operate this way? To understand the economics of scripted television, we need to examine the idiosyncratic journey of a show from concept, to pitch, to script, to screen. And we’ll see why, in a business where only a few hits stand out any given year, lavish spending is the cost of staying relevant.

The Creative Marketplace

Credit: Sony Pictures Television / NBC

George: The show is about…nothing.

Jerry: Well, it’s not about nothing–

George: –No, it’s about nothing!

Jerry: Well, maybe in philosophy. But even nothing is something.

— Seinfeld, “The Pitch”

A TV show begins its life in one of four larval forms: a pitch, a script, a piece of source material, or a talent deal.

A pitch involves writers and agents presenting concepts to studios, production companies, or networks. Five hundred or more pitches may wend their way through the system in any given year. Only a few are chosen for script development. The strength of a pitch has as much to do with the team behind it as it does the concept. As the old saying goes: ideas are worthless; execution counts. An inexperienced or obscure writer is unlikely to get a pitch meeting and unlikelier still to close a deal. A writer or producer with a strong track record, on the other hand, can sometimes sell a pitch with little more than George Costanza’s logline.

Alternatively, a show could develop from a speculative or “spec” script pitched “around town” by a writer’s agent. Spec sales occur throughout the year, though a lot more specs get shelved than sold. They are also more common in the movie business than in TV. Evaluating the merits of a season of episodes involves thinking about more than a single script.

A hot spec – an original project from a writer with a hit-filled track record or the rare buzzworthy project from a newcomer – can easily fetch six figures. Its price depends to some degree on the quality of the script, but more so on the degree of interest the project generates around town. High spec prices usually result from bidding wars between the networks.

Other shows originate with the purchase or optioning of a piece of intellectual property. This could be a book, a newspaper article, a blog post, a video game, or even the rights to someone’s life story. Sourcing material is often the cheapest way to develop a concept. It can also be the riskiest, especially if the IP holder is unqualified to transform the concept into a full-fledged show. This is why networks often hand off sourced concepts to established writers to flesh out.

The hottest writers in Hollywood even have shows pitched to them. In what’s known as a “blind deal,” a studio pays a writer a handsome figure – often in the millions of dollars per year – to flesh out scripts based on any ideas the studio and the writer dream up together over the life of the contract. The writer is “blind” in the sense that she is committing to developing scripts for a buyer before the ideas are fully baked.

Breaking Bad started as a concept that X-Files veteran Vince Gilligan developed as a struggling and intermittently employed writer. Gilligan attracted the interest of Sony, who joined him in pitching the idea to networks around Hollywood. Gilligan admits that the pitch “was turned down all over town” before AMC purchased it. At the time, AMC was an unlikely buyer as smaller cable networks like AMC had only recently entered the scripted originals game. Since then, AMC has had a string of hits with Breaking Bad, Mad Men, and The Walking Dead.

With the entrance of outsiders like AMC, Netflix, Amazon, and Microsoft, there are more buyers in the marketplace than ever before. Depending on the stage of the idea, a would-be show could be bought or optioned by a production company, a studio, a distribution company, an individual producer, or a network.

If the lines between these entities seem blurry and confusing, don’t worry; an in-depth exploration of the tangled web of media companies involved won’t help. The vertical and horizontal integration in the TV industry can be staggering.

To take one example: 20th Century Fox, a holding company, owns Fox Television Studios (a production company), 20th Century Fox Television (a production group and studio), 20th Television (a syndication and distribution company), and Fox Broadcasting Company (the network, also known as FBC or simply as Fox). 20th Century Fox is in turn a division of Fox Entertainment Group, itself a subsidiary of 21st Century Fox, which also happens to own the Fox movie studio. Until June 2013, all of these entities were owned by another parent company, News Corporation.

Even insiders have trouble prying apart the intricacies of the system. This author worked at 20th Century Fox Television in the mid-2000s and couldn’t tell you who signed his paychecks.

A 98% Failure Rate

In some ways, TV networks are like venture capital firms. They place a series of bets, many of them quite expensive, on a portfolio of pilots: proof-of-concept episodes for prospective series. Only a small number of pilots will become shows, yet a typical half-hour comedy pilot costs $2 million to shoot, and an hour-long drama costs about $5.5 million. And that’s just for shooting the pilots themselves; those costs don’t include the millions of dollars spent acquiring and developing scripts, pitches, and talent deals.

The 2012-13 “development season,” which ran from January to April, saw the production of a record 186 pilots for broadcast and cable television. The Hollywood Reporter, a trade paper, estimates that the networks spent $712 million shooting those pilots.

That level of investment looks even higher when we consider the odds stacked against any given project. Fox, for instance, shot 8 dramas and 8 comedies for the upcoming Fall 2013 TV season. Of these 16 pilots – each of which was subsequently screened for executives and focus groups – only 9 were selected for the fall lineup. Competitor ABC ordered a heftier slate of 12 dramas and 12 comedies, of which 8 shows made the cut.

For those keeping score, that’s a pilot-to-series rate of 56% for Fox and 33% for ABC. Using industry production-cost averages, we estimate that Fox spent $60 million to bring 9 shows to the air, and ABC spent $90 million to bring 8 shows to the air.

Within the industry, that’s a great year. Variety estimates that one pilot is produced for every 5 scripts purchased. And in a typical year, a network will order about 20 pilots and bring 6 to the air. That means a script has a 20% chance of being produced as a pilot and a 6% chance of being aired on television. A writer who sells her script has a depressingly small chance of ever seeing it on the air.

But wait – it gets worse. Of all the pilots aired on a new TV lineup, only 35% will air longer than a single season without cancellation. So the odds of a script achieving success are actually closer to 2.1%. To put it another way, any given script a network buys stands a 98% chance of commercial failure.

This process may strike the astute reader as absurd. Given the millions of dollars thrown around every development season, and assuming that 98% of scripts in development fail, how on earth do networks stay in business? Why can’t they find a more scalable, more efficient, less expensive way to test concepts?

The answer has a lot to do with how networks make money, and the very structured way in which TV advertising is sold. And Hollywood’s inability to predict the next hit doesn’t help.

The Biggest Show of the Year

The bulk of TV advertising sales takes place every May in New York at a series of presentations called the “network upfronts.” As the name implies, networks sell their new schedules months in advance. Up front. This is sort of like having to sell 5-year financial projections to an investor, and then being held strictly accountable for hitting each number. Advertisers don’t like to gamble on whether a show will exceed expectations. Uncertainty is the enemy. But almost nothing is certain about the fate of a show this far out.

Big advertisers, such as Coca-Cola and Procter & Gamble, spend hundreds of millions of dollars each May. While they can and do make buys on individual programs (particularly on big hits like American Idol or The Big Bang Theory), they can negotiate better terms by agreeing to set levels of spending on a given network across a bundle of its programs.

Many of those shows, especially the new ones, are still in various stages of production. Nevertheless, they must be presented as if in finished form. This is especially tricky for pilots, which are essentially proofs of concept. Advertisers will scrutinize them at the upfronts, often on the basis of short clips and word of mouth. A poorly received pilot is unlikely to attract advertising dollars. In this sense, the upfronts serve as the final gating mechanism before pilots can secure a spot on the air. Small changes can be made to the schedule – a shuffling of the deck chairs, so to speak – but it’s too late to shoot new pilots to fill any gaps that emerge during the upfronts.

This system forces networks to place a polished facade over the chaos of the creative process. It strongly discourages the network from showing rougher, more minimal concepts to advertisers. Advertisers can’t tell the quality of the product from clips of the pilot. Instead they judge the confidence the network projects in its slate. A successful upfront presentation is more Steve Jobs than Steve Wozniak.

Furthermore, networks have their own brands to worry about. The risk associated with a string of failures can be quite high and hard to recover from. NBC, which has languished near the bottom of the ratings pool for a few years in a row, now suffers from the lowest average advertising rates of all the major networks.

Due to the fixed upfront schedule, iteration (improving or tweaking the show multiple times in response to viewer feedback) is also challenging. A show either looks good in May or it gets the axe. There’s very little time to make changes before the start of the Fall season. If everything gets the axe, there’s no time to develop something new. Shows that do survive the upfronts need to be staffed right away and their writing staffs to get cranking. As many as four scripts could be finished by the time the pilot debuts on TV, so there’s no room to respond to the show’s first reception by a live national audience.

This is perhaps the biggest reason why networks keep so many projects in development each year: to hedge their bets. Networks operate in an environment that demands up-front commitments against uncertain outcomes; their best way to mitigate the risk is to have many, many pilots as fallback options.

None of this would seem necessary if the networks had a halfway decent way of predicting success in the first place. They do conduct market research (usually in the form of focus groups) while in pilot production. But judging the future success of a show is extremely difficult at all stages of development.

As Amy Chozick of the Wall Street Journal puts it:

“All kinds of things can turn a promising idea into a flop. Casting may not click. A story line that made for a compelling pilot can’t hold an audience’s interest for 22 episodes a season….Overly acquiescing to focus groups can lead to a bland finished product…”

David Madden, President of Fox Television Studios, states the case more bluntly:

“Most movies fail, most books fail, and most albums aren’t that good, whether they’re by committee or solo practitioners.”

Perhaps networks wouldn’t need to hedge their bets by spending hundreds of millions on pilots if their creative experience, development process, and top talent gave them a predictive edge. But year after year, none of it seems to.

The Importance of Exclusive Content

The biggest broadcast networks, such as ABC, NBC, Fox, and CBS, make hundreds of millions to billions of dollars each year from ad sales. But they also make quite a bit of money (sometimes 50% or more) from licensing and distribution fees. Basically, this is revenue earned from selling the rights to cable companies, satellite providers, and other major distribution channels to carry the networks’ branding and programming.

Distribution fees are important to broadcast networks, but they’re extremely lucrative for the most in-demand cable channels, such as ESPN, that few people would subscribe to cable packages without getting. This is why NBC paid $1.2 billion for exclusive rights to the London Olympics, but ESPN is paying $15.2 billion to the NFL. It gives them must-see television that they can, in turn, use to demand higher distribution fees.

Many of the smaller cable companies, like AMC, started out as redistributors of old content: black-and-white movies from the ‘50s, say, or reruns of broadcast series. A cabler in the rerun business might earn a modest amount on advertising, especially if it curates a portfolio aimed at a specific demographic (old shows for old people, for instance). But it’ll earn a lot more money through fees from Comcast, DirecTV, and other service providers.

Either way, the rerun business is a pretty boring one, and with the advent of Netflix and other VOD (video on demand) services, it’s also a dying one. Why sit around watching an old movie channel when you can push a button on Netflix and get exactly what you want, when you want it?

AMC saw the writing on the wall back in the late 2000s. It faced a critical choice: continue to reap steady profits from rerunning old movies, with the long-term risk of extinction – or differentiate itself from the pack by making its own shows. It embraced the second option, choosing to bet the farm on original programming with the debut of Mad Men in 2007. Critics took notice, and audiences slowly trickled in. Breaking Bad followed in 2008 and 2010 saw the launch of hit series The Walking Dead.

None of this success was assured, however. Breaking Bad debuted in 2008 to an audience of only 1.4 million – not bad for cable, but by no means a hit. The audience grew, however, thanks to a rabid and digitally connected fanbase. Weekly viewership increased to an average of 2 million in 2009, then to 2.58 million in 2010. Then the audience nearly doubled between 2011 and 2013, with more than 5.9 million viewers tuning into the premiere of the final season. (The Daily Variety, a Hollywood trade publication, credits a 2011 partnership with Netflix for the big jump. With Breaking Bad’s entire back-catalog available online, the show was discovered by a secondary audience, all of whom could catch up in anticipation of the home stretch.)

With the rise of Mad Men, Breaking Bad, and The Walking Dead, AMC has gone from late-night backwater to must-see TV in only six years. Its rise was sudden, and its success is now dependent on an entirely new rulebook – the one big networks follow. It’s a business driven by the short run: quarterly and yearly ad sales, fluctuating viewership numbers, and increased scrutiny from the press and advertisers. A string of hits elevated AMC from a $750 million company in 2007 to a $1.25 billion company in 2012. And only hits will keep it there.

The Anatomy of a Hit

AMC monetizes Breaking Bad in two major ways: through on-air advertising and through distribution to cable providers, home video, VOD services, and a few international markets.

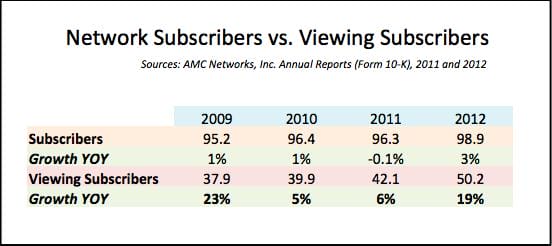

In AMC’s case, distribution revenues are a function of Total Network Subscribers, or more precisely, the number of TV-watching homes who happen to subscribe to any cable package that includes AMC. This figure didn’t change much from 2009 to 2012 – from 95.2 million to 98.9 million. This is typical: cable contracts are complex, multi-year affairs, locked in over long-term periods with providers like Comcast and DirecTV.

But let’s take into account Viewing Subscribers. Viewing Subscribers is, as the name implies, a measurement of how many people are actually watching the network.

It’s a more volatile number, driven directly by the performance of AMC’s programming. Viewing Subscribers is largely responsible for advertising revenues, which are pegged to active eyeballs the network can claim to reach. Since at least some advertising is sold on a short-term basis throughout the year, a show like Breaking Bad can affect ad sales in two ways: increasing viewership or putting a price premium on ad units.

Here we see the growth in Viewing Subscribers vis-a-vis Total Network Subscribers in the same timeframe:

Note: figures are listed in millions of viewers

Viewing Subscribers grew like gangbusters in 2009 at 23% year over year (Breaking Bad premiered in 2008 and first gained traction in 2009; Mad Men had premiered in 2007). It increased at a respectable clip in 2010 and even in 2011, despite a small decline in Total Network Subscribers. And it grew at 19% from 2011 to 2012, the same year Breaking Bad doubled its audience size.

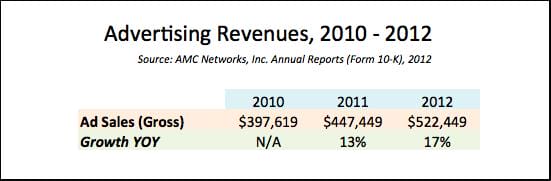

To determine the show’s effect on the network’s revenue, we need to hit the books. AMC Networks earned $1.25 billion in revenues in 2012, about 41.7% of which came from advertising, and 58.3% came from distribution and affiliate fees. As discussed, the 41.7% is the figure we care about in our analysis; it’s the one driven directly, year over year, by the shows on the network.

Here are AMC’s ad sales over the past three years:

Note: figures listed are in thousand-dollar units, so $522,449 means $522,449,000

While we don’t have a growth figure for 2010, we can see that growth in ad revenues was impressive in 2011 and 2012, the years that coincided with Breaking Bad’s mainstreaming, as well as the continued success of Mad Men and The Walking Dead (launched in 2010).

AMC’s financial reporting doesn’t offer us an in-depth glimpse into the precise effects of Breaking Bad, Mad Men, The Walking Dead, or other shows on its ad sales or benefit compared to their cost. But this handful of shows appears to have driven a $75 million increase in ad sales last year.

And ad sales are becoming an increasingly important part of AMC’s business: up from 36% a few years ago to the more broadcast-like 41.7%. To the extent that AMC’s ad business grows, and its ad business becomes more systemically important to its overall health, it’s going to be even more dependent on hits, and on keeping a steady (and expensive) pipeline of content in the works.

Recall that AMC raised the price of a 30-second spot on the finale of Breaking Bad to as much as $400,000. That’s no small accomplishment. It’s approximately double the rate advertisers pay for prime time spots on much larger broadcast networks, with much larger viewership numbers:

In this case, an exclusive, high-quality hit paid off. The show’s critical acclaim, upscale audience, and media spotlight allowed the network to charge a significant premium on the 10 million viewers who tuned in for the show’s final episode. (An audience of 10 million is huge for cable, but regular primetime programming on big networks routinely meets or exceeds that number. The top-rated broadcaster, CBS, pulls in about 11.9 million viewers on any given weeknight.)

But that was the show’s finale, after all, and now it’s gone. These days, a Breaking Bad-less AMC will find itself head to head against a set of increasingly risk-seeking and heavily funded competitors. One of those competitors is Netflix, the distribution partner largely responsible for Breaking Bad’s mainstream breakout.

The Fight for the Future

Why would Netflix – to say nothing of Amazon and Microsoft – want to copy the AMC model? After all, Netflix is a healthy business with lots of subscribers. It’s the on-demand platform of choice for millions of viewers, perhaps even cannibalizing those viewers from the TV networks themselves. It’s a direct-to-consumer subscription business; it doesn’t seem to need advertisers. And, as a distributor, it doesn’t need to rely on selling itself to Comcast or DirecTV. In fact, in many ways it’s competing against them.

But without exclusives, Netflix is in a similar situation to the pre-originals AMC. It’s a rebroadcaster, offering old programming. It competes on breadth, assortment, and convenience of delivery – but networks and studios have increasingly come to fear it. They’ve started negotiating for higher licensing fees, and many have pulled their content from Netflix altogether. (Netflix lost the rights to nearly 1,800 titles in May of this year alone.)

Netflix can’t afford to hemorrhage its library and risk being outcompeted by Amazon, iTunes, or other on-demand services. So it’s making big bets on original content of its own, odds be damned. And its competitors are doing the same.

What puzzles this author is why they’re developing content the Hollywood way. To some extent, they’ll need to pay top dollar for the best actors, writers, scripts, and pitches. But there is no valid reason why Netflix should have placed a blind, $100 million bet on a new series. Of all the distributors of television programming, Netflix is in the best position to develop more lean and nimble proofs of concept and to serve them to the right audience.

Unlike a traditional TV network, Netflix has the unique ability to put content in front of millions of targeted, interest-based viewers in incredibly short order. It has better taste profiles and matching algorithms than AMC, ABC, or big advertisers could ever dream of. Why, for instance, couldn’t Netflix buy scripts – or hell, get into the blind script business with established writers – and then test them out before fully committing to them? Why not let the market decide, without the pressure of advertisers or distribution partners?

There are perils in listening too closely to consumers, and no one wants to design by committee (least of all the writers). But there’s a big difference between the network design committee that currently exists – namely, a handful of executives and randomly picked focus groups – and a “committee” of audiences whose tastes and preferences are known, who can be segmented, and who might find interaction with the development process a rewarding “exclusive” in and of itself.

A direct-to-consumer approach would save time and money and reduce risk. Even better, it would empower audiences and give content creators better odds of getting their material in front of viewers. And it would reduce the artificial constraints on the development process placed by the advertising sales cycle – constraints that Netflix has no need to obey.

The best way to make a hit is to build and nurture a fanbase. The networks of the future – the ones with built-in audiences and distribution systems – should make better use of their ability to do so. Instead of trying to guess at viewers’ reactions, they should tap into them. TV will always depend on hits, but there are far less crazy ways to find them.

This post was written by contributor Jon Nathanson. Follow him on Twitter here. To get occasional notifications when we write blog posts, sign up for our email list.