Metallica is one of the most successful bands of all time. They’re also the example given in the Wikipedia page for “selling out.”

It’s hard to stand out from a crowd by being the same as everyone else. But once the crowd knows you, average is good. That’s true whether you’re an aspiring Senator or an aspiring musician, and that’s why we complain about sellouts so bitterly and so often.

In 2009, Marco Rubio, the Republican former Speaker of the Florida House of Representatives, was a longshot to win a Senate seat. When Rubio announced his candidacy, Florida’s governor Charlie Crist was the assumed winner, backed by the Republican leadership. Rubio had only 4% of the vote in early primary polls and trailed Crist by 30 points early in the race.

On election day, however, Rubio decisively defeated both the Democratic nominee and Crist — who had dropped out of the Republican primary to run as an Independent in the face of Rubio’s rising popularity. Rubio campaigned on his life story as the son of poor immigrants, but he also embraced the Tea Party. He portrayed himself as an outsider and champion of fiscal responsibility (and lower taxes). He stressed his opposition to Obamacare and the stimulus plan that his opponents supported. The highly energized and mobilized Tea Partiers helped him defeat an overwhelming favorite.

The victory made Rubio a nationally recognizable Senator. The press speculated about his presidential potential and Romney considered him as a running mate. (A Tea Party poll found him to be the favored Tea Party vice presidential pick.)

But once Rubio acceded to the national stage, his favor among the Tea Party cooled. He worked with Democrats on an immigration bill that represented the bipartisanship the Tea Party shunned and seemed to violate his campaign pledge of not giving “amnesty” to illegal immigrants. He expressed support for Mitch McConnell, a member of the Republican establishment that the Tea Party wanted to overrun. Former supporters assumed that Rubio was turning his back on them to curry favor with Washington insiders and the broader public for the sake of his presidential ambitions. Some began to label Rubio a “sellout.”

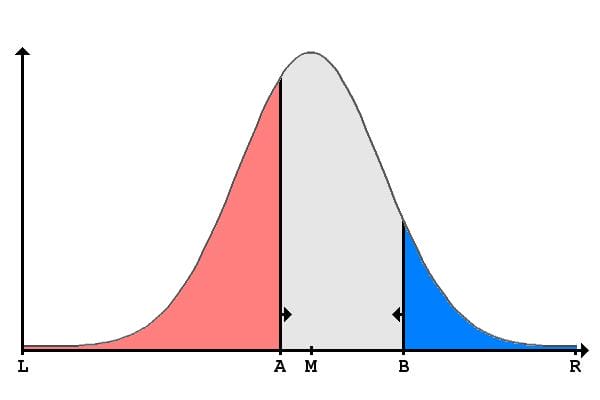

Political scientists would describe Rubio’s sellout as responding to the incentives of the median voter theorem. If you assume that voters can line up candidates along one dimension (so from very liberal to very conservative), the theorem states that the winner will represent the values of the voters in the middle of the electorate. If you’re Mitt Romney facing Barack Obama, you know that the most conservative voters will go for you over Obama. So why not take a more moderate position to fight Obama for centrist voters?

So long as they can do so without alienating their more partisan supporters, candidates A and B should take more centrist positions to win over median voters.

The theorem is a fancy name for the simple incentive that explains why politicians’ “move to center” when they switch from a primary to a general election (or a more liberal or conservative state to the national stage) and why all candidates seem the same: In a winner takes all situation, the most average candidate usually wins.

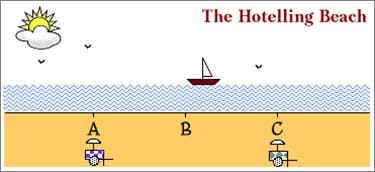

The median voter theorem is an application of the principle of minimum differentiation. The classic example of this tendency to converge on the middle is the location of two hot dog stands along one stretch of beach. It would make the most sense for each stand to stake out a spot a third of a way from each end of the beach (spots A and C). But as each stand can steal customers from the other by moving toward the center of the beach, the owners have an incentive to do so. Eventually the two stands will be side-by-side in the center of the beach at point B, even though they may lose out on customers at the ends of the beach.

Graphic from Wikispaces Classroom

Less theoretically, the principle explains why products may look the same rather than serve a niche or boldly differentiate. In a market of two dominant phone makers, for example, one could make a phone for technophiles while the other makes a simpler model. But as they fight for the average user, the phones could become nearly identical. And just as the principle applies to politicians who sell out, it can describe sellout musicians who “go mainstream” like politicians “move to center.”

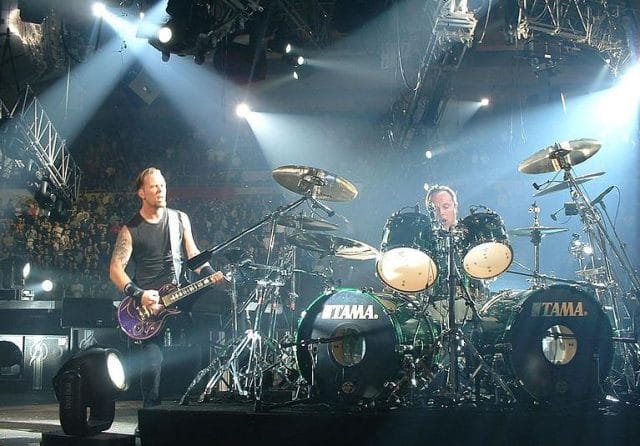

The Wikipedia page for “selling out” describes Metallica as “an example of an artist being accused of selling out.” The group began as a heavy thrash metal band that attracted distinctly non-mainstream supporters. (Not only is metal a niche, but stylistic choices like a nine-minute stretch without lyrics in their second studio album clashed with the average listener’s expectations and radio play formats.) For their sixth studio album, Metallica hired a producer who had worked with Aerosmith and Bon Jovi and moved away from thrash and metal toward a more general rock sound. The producer explained that the band’s sound changed “to make the leap to the big, big leagues.”

And they did, as the album became one of the most commercially successful of all time. Fans debate if and when Metallica sold out (and whether they accept the change as an “evolution” of musical style, much like Rubio supporters debate the sincerity of his bipartisanship), but to many, their actions were clear: Metallica had given up their sound in favor of more generic, mainstream songs that would sell outside the thrash metal niche.

Why We Hate Sellouts

One conception of selling out focuses on figures that use their work or position for commercial gain. This is especially true of musicians who sell the rights to their songs for advertising purposes. Fans want the purity of a true artist. They don’t want Lady Gaga featuring Miracle Whip in a music video because the company paid for the product placement.

The other conception, which we’ve focused on, is the move mainstream. And remembering the principle of minimum differentiation, we can see why fans and supporters hate it so much: It leaves the market underserved.

Fans of niches like thrash metal find that their favorite groups are continually tempted away from the genre. They are like the people on the beach, far away from the hot dog stand, and voters on the far left or far right who can’t find a champion to represent them. Politicians’ (bands’) move to center results in a world of bland, inoffensive, and identical candidates (music). Snobs complaining about popular bands’ later albums and figures blasting politicians’ bipartisanship can be annoying. They also serve as the only force fighting the market failure that pushes everyone toward the middle.

But there’s more to people’s hatred of sellouts.

With all due respect to artistic integrity, if the only obstacle between the average starving artist and a platinum album was his artistic sensibilities, all music would sound exactly the same. Being bland is helpful to famous names who want to maintain a big tent. But sounding mainstream doesn’t help artists without name recognition. They’ll just be lost in the crowd. It doesn’t matter how big your tent is if no one is going in.

Instead, new musicians (politicians) need to stand out. The consumers (voters) who seek out unknown names have fringe musical tastes (voter preferences) that the bland mainstream is underserving.

So artists (and politicians and so on) need to differentiate when they start their careers to attract members of the energized, disaffected niches — the thrash metal devotees, the Tea Partiers — who can propel them to major music venues or a high office. It’s only once these niches have fueled an artist’s or politician’s rise that the logic of going mainstream applies.

This is why sellout is such a dirty word. A sellout doesn’t just choose commercial success, he betrays his original supporters in a very personal way. A sellout convinces a group of supporters — who are used to being abandoned by their champions — that he is truly like them. And then once that subgroup is won over and makes his career, the sellout abandons them for the more lucrative world of mainstream success that his supporters gave him access to, the world where centrism and unoriginality is rewarded.

People in careers like politics and music that are strongly tied to identity can try to be upfront about their ambition or interest in commercial success. But there are no honest sellouts.

This post was written by Alex Mayyasi. Follow him on Twitter here or Google Plus. To get occasional notifications when we write blog posts, sign up for our email list.