Editors note: This guest post was written by Jim Pagels. Image via Flickr.

In the bar and restaurant industry—where profit margins are razor-thin and floor space is limited—it’s essential to have a decent crowd nearly every night. Most people, however, only get drunk on Friday and Saturday nights. So how do you entice customers to get loaded on a weeknight? One popular answer: hosting a trivia night.

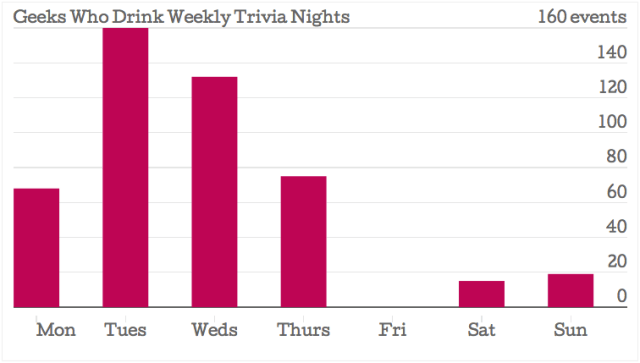

Trivia night, sometimes called pub quiz, is becoming more widespread, enticing patrons to answer questions and compete for prizes at their local bar. Increasingly, many bars outsource their competitions to specialty companies that produce weekly sets of questions and hire a network of part-time hosts. Geeks Who Drink is one of the larger firms, hosting 469 weekly bar trivia nights across the country. Data from the company’s website shows that Tuesdays and Wednesdays are far more prevalent compared to other weeknights. It’s no surprise that there aren’t any Friday night events and only a handful of trivia nights on Saturday, given that those nights don’t need any help drawing crowds.

Source: Priceonomics data crawling

Origins and Rules

In the mid 1970s, England natives Sharon Burns and Tom Porter traveled across the UK promoting their “pub quiz” service to local breweries as a promotion during low-revenue weeknights. The events were highly organized, with 32 teams in three separate leagues competing in head-to-head matches and sending the results to Burns and Porter to update the league standings.

After the success of the board game Trivial Pursuit in the mid 1980s, pub quiz took off and spread to America, where the competitions became known as “trivia nights.” Pub quiz is still more popular across the pond, though, with one estimate of 22,445 weekly events in the UK compared to only 2,000 in the U.S., which is 55.7 times as many trivia nights per capita compared to the United States.

According to one British trivia game show star, trivia nights skew younger in America, with most American players in their 20s and 30s. Players usually compete in teams of 4-10 members, with strict limits on the number of participants per team. Most American trivia nights are informal and free of charge, with the participants only playing for gift certificates or discounts on their tab. In England, however, where gambling is legalized, it’s not uncommon for teams to pay an entry fee, which is pooled together to award cash prizes.

Bar owners often write their own questions, but a growing cottage industry of third party companies now write questions and host trivia nights. As the aforementioned Geeks Who Drink puts it, “Most quizzes are written by people with day jobs – and it shows.” Any topic is typically fair game, with the difficulty usually increasing through the night. As one New York host once described the perfect question: “At least one person in the room should know the answer, at least half the people in the room should be able to make an educated guess, and everyone in the room should find the answer interesting.”

The Economics of Trivia Night

So does investing in trivia night pay off? It seems like the answer is yes, though how much depends on who you ask.

Geeks Who Drink and TriviaTryst — a company that hosts 30 weekly events, mostly in New York City — usually charge bars about $150 to $200 per event, according to the five bars we spoke to. While it varies a little from place to place, hosts make about $50 per night with a $25 bar tab.

Trivia Tryst advertises that its trivia nights increase average sales by 300 percent, and Geeks Who Drink claims its clients report “anywhere between three to 10 times the revenue.” The bars we spoke to confirmed increases in sales on trivia nights—but not quite at the highly lucrative rates the trivia companies advertise. The increases in sales on trivia nights can range can range from 30 percent, according to Bobby Derian, an employee at Pub On Pearl in Denver, Colorado, to 65 percent, according to Tyron Edwards, manager of Addison Ice House in Addison, Texas.

“[Sales] depend on the crowd and the mood. Sometimes drink sales go way up, sometimes they kind of stay the same. It just really depends on the vibe,” Edwards said. Derian offered a similar perspective. “It kind of goes both ways,” he said of trivia’s effect on sales. “You get those couple tables that just kind of hang out and buy Cokes, but a lot of the tables do a fair amount of drinking.”

Dave Hunt, a manager at Coogan’s Restaurant in New York says the bar’s Wednesday Trivia Tryst event has about 40 players who average $22 to $25 per person in sales but notes, “How many would be here anyway is hard to calculate.” Hunt reports that Coogan’s generally takes in an additional $800 on trivia nights, of which he says $200 goes to food and beverage costs, $175 to Trivia Tryst, and $85 to gift card prizes, leaving just $340 in profit.

While the actual boost in sales doesn’t seem to match trivia companies’ estimates, the events still appear to be a solid investment for a pub with slow weeknight business; the the investment in pub quiz seemed to pay off for everyone we interviewed. Additionally, many of the bar managers we spoke with mentioned trivia nights attracting repeat customers who also stop by other nights of the week—a highly valuable asset for any business. But other promotions might still be better options. According to Hunt, Coogan’s once hosted karaoke events regularly, and he said that all those nights were overwhelmingly more successful than trivia.

The Evolution of Trivia

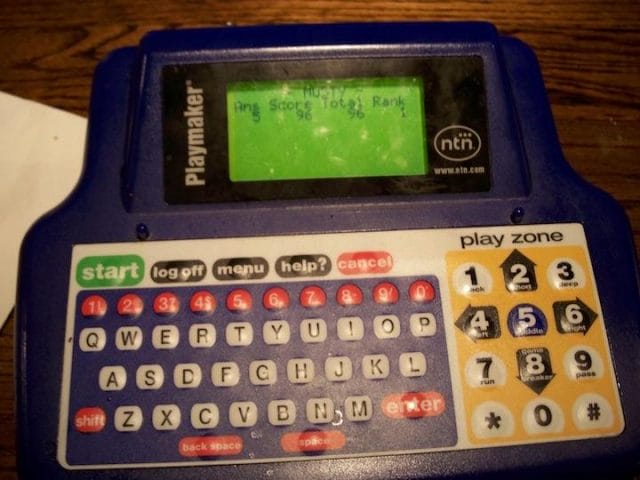

While most modern trivia nights are conducted with pen and paper, the competitions in the 1980s and 1990s were once far more technologically advanced. An example of this era comes from a July 1989 New York Times story about a nationwide trivia game interconnected among over 400 bars across the continent by phone lines and satellite signals:

“Patrons at the approximately 300 bars in the United States and Canada that have the game use portable computer terminals to select answers to questions that appear on a large monitor on the wall. A typical game includes 15 questions, and participants are given cumulative scores after each question. When a game ends, the monitor displays the name of the winner in the bar and gives results from other bars.”

The game, hosted by a California company called NTN Entertainment Network, regularly awarded vacations, VCRs, and other electronics to each night’s national high scorers, while bars handed out smaller prizes to local winners.

While most current trivia nights space out questions to keep customers in the bar longer, speed was of critical importance to NTN, with teams commonly employing a “finger man” to rapidly select multiple choice answers displayed on a central TV screen and earn bonuses for quicker responses.

NTN device via Wikipedia.

NTN was so popular that it held an annual national championship and created specialty sports and TV games such as a nationwide ER trivia game during the popular show’s season premiere in 1997, paving the way for the modern Game of Thrones and Breaking Bad-themed trivia nights. (Geeks Who Drink recently conducted a 28-city Harry Potter trivia night event, and another New York company, Trivia, AD, exclusively hosts nightly themed events on topics ranging from Wet Hot American Summer to WWE wrestling.) The company also had live sports games, in which players would try to predict the plays of football, baseball, and hockey games in real time, and marketed its services to businesses like Chevrolet, which used the game at dealerships in the early 1990s to build prospective customer lists.

In the late 1990s, however, the company’s dismal financial performance made it difficult to raise money, leading to rampant equipment issues that drove the one-time luxury item of many American bars to near extinction.

Clashes with Technology

Since the demise of NTN, trivia has taken a drastically anti-technology approach, with strict no-phone rules to prevent players from looking up answers online. One British pub is so adamant about the rule that the owner connects an FM tuner to the P.A. system, which will cause loud electronic interference to resonate should anyone so much as turn on his or her phone. Another bar plays covers of songs during “name that tune” rounds rather than the original recording to prevent players from looking up song titles on the popular app Shazam. It’s impossible to completely stamp out cheating, though, and incidents have gotten ugly in high stakes U.K. games. It’s not uncommon for such disputes to result in brawls. In one case, a game even had to continue with a participant playing from behind bars.

The prevalence of technology has caused some to question the place of trivia nights in the 21st century. In an age in which the answer to any question is only a few keystrokes away, memorizing vast quantities of information might seem to be a thing of the past, akin to penmanship and spelling skills.

“Do we really need to study anymore, or can we rely on our thumbs?” University of Pittsburgh psychology professor Christian Schunn once asked. “More stuff is being thrown at you and each is sticking less … Is the lack of stickiness winning or is the number of things being thrown against your mental wall winning? It’s a tension between those two things.”

On the other hand, some bars have embraced technology, asking competitors extremely obscure questions and creating smart-phone races to look up the answer.

One thing seems constant over the years: Trivia nights bring together consistent, local communities. In 1989, the Times reported that “the same teams show up week after week.” Over twenty years later, in 2011, the same paper noted, “It’s common to see the same players compete around the borough, with groups of friends forming steady quads.” Trivia seems to have come full circle technology-wise, but what’s changed is the monetization of the game, spread to a wide, international audience—one more than willing to have a few beers on a Tuesday night.

This guest post was written by Jim Pagels. Follow him on Twitter here.