If the phrase “fall through the cracks” applies to anyone, it is the children of the foster care system.

In 2012, 397,122 American children lived in foster care, which represents 0.5% of the under 18 population. Due to either child abuse, neglect, or a parent’s death, they became wards of the state, placed in temporary homes or institutions by a foster care agency. State investigators, assisted by police officers, took some of these children away from parents that hit or pimped them. Others they removed because a doctor reported that a child was malnourished or a parent failed to administer a baby’s medication. Parents sometimes leave their children at foster agencies themselves, using them like adoption facilities.

The goal is for every child to return to her biological parents once it is safe, or to be adopted by new parents. But only 50% return to their families, and every year around 24,000 kids “age out” of the system at age 18 or 21 without a family to belong to.

In the interim, most bounce around between homes — often dropped off at the curb of the foster care agency with a trash bag full of possessions by their frustrated foster parents — or even reside in institutions all too reminiscent of jails.

As adults, former foster children fare poorly by just about every metric. They experience more unemployment, poverty, and mental health problems, are less educated, and face incarceration at high levels. By some estimates, 30% of the homeless population went through foster care.

The foster care system may be the largest, most impactful program to garner so little national policy debate and media attention. And those that know it best don’t paint a pretty picture. Cris Beam, a foster mother and author of To the End of June: The Intimate Life of American Foster Care, describes her frustrations:

“I was amazed that we could spend more than 20 billion dollars a year in this country on a system that nobody—not the foster kids, not the foster or biological parents, not the social workers, not the administrators or commissioners—thinks is working.”

Like any system of its size, foster care is complex, and its triumphs and failures not easily digestible. But outsiders can understand much of foster care’s failings and the difficult trade-offs it faces by recognizing how the system plans for the best — either a happily ever after return of foster children to the biological family once deemed unfit to care for them or adoption by a new, loving family — in an environment where disappointment and dysfunction are the norm.

The Nanny State

The entrance of a child into the foster care system begins with a state investigator deciding that a minor needs to be removed from his or her home. Immediately thereafter, a social worker begins discussing a plan with his or her parents to get the child back under their care.

Investigators make home visits mainly in response to tips. Hotlines exist so that anyone can report suspicions of an abused or neglected child, and teachers, doctors, police officers, and members of several other professions are often legally obligated to do so. Investigators can enter a home and interview parents and their children without a warrant.

The federal government sets broad policies about removing children in conditions of abuse or neglect and leaves the definition and administration of those policies to the state. So it is state guidelines that govern investigators’ decisions. In many states, for example, the presence of illegal drugs mandates a child’s removal.

One quarter of removals are for abuse and three quarters are for neglect. As Cris Beam notes in The Intimate Life of American Foster Care, however, abuse is often a matter of perception (consider the uneven rise and fall of the acceptability of corporal punishment) and “many argue that ‘neglect’ is a code word for ‘poor.’” This leaves social workers, often recent graduates in their twenties, to decide what combination of dirty sheets, intoxicated parents, curdled milk, and so on constitute an “imminent risk” to a child’s safety.

Investigators bring the removed child to an office where social workers begin calling the child’s extended family or even acquaintances. If no one can be found, the first foster agency with an opening places the child in a foster home. The foster agencies are nonprofits, contracted by the state to place foster children, provide services, and manage the relationship with the foster and birth parents. Beam refers to the random selection of an agency as “roulette” since the nonprofit agencies “vary in aptitude as much as they do in approach.” Kids could land with a small, well-managed Christian foster agency, a large, dysfunctional, secular nonprofit, or anywhere in between.

The government remains in charge of legal decisions about the minor’s fate, and a judge at “family court” rules on decisions to remove children within a few days. (If they did not do so already before the child was removed.) The judge not only reviews the investigator’s decision; he or she also rules on the conditions under which the parents can reclaim their children.

Many regions task the parents, a caseworker, and an advocate for the parents with creating a reunification plan to present to the judge. As Beam reports on this “family team conferencing” model in New York, the professionals may suggest that “Grandma move in” or that a parent with substance abuse problems attend rehab. But in the end, a judge, who reviews around 50 cases a day in New York, decides exactly how, when, and under what conditions parents will get their children back.

It is strange that the very first thing the government does after deciding that a child must be taken away from his or her parents is plot to return that child to the very same home. Of course, it also makes sense. The state is an uneager nanny because — in ideal circumstances — children belong with their parents, and no one wants to take away parents’ rights except as a last resort.

Judges rule on the adoption of foster children. Source: WTNH

Legal Purgatory

If childhood is a time for kids to root themselves firmly in the soil, the system often fails foster children by uprooting them so often that they have no chance to grow.

One of the most important psychological ideas for foster care is attachment theory. It’s the theoretical underpinning of the common sense notion that children benefit from stability. It focuses on the importance of the relationship between infants and their caretakers. A parent is like a base of operations, allowing kids to explore the world and still retreat to the safety of their parents.

As Cris Beam notes in her book, foster care leaders have recognized the damage of breaking those attachments since attachment theory cropped up in the 1950s. It contributed to the move away from orphanages to foster homes. But the uncertainty of reunification plans still makes the life of every foster kid unstable. Babies experience the shock of being passed between their biological and foster parents. Older children never know if their parents will meet the conditions set by the judge.

When parents fail to meet the benchmarks of their plan, the judge generally revises the reunification plan. For a long time, this resulted in “drift.” Foster kids were strung along by ever lengthening reunification plans, waiting for a happily ever after that never came.

In 1997, Bill Clinton signed the Adoption and Safe Families Act (ASFA) to reduce the time spent in limbo by foster children and prevent their return to unsafe homes. It offered incentives to states and parents to boost adoption rates. It required yearly hearings to discuss the permanent status of foster children and stated that parents whose children spent 15 of the last 22 months in the foster system would lose their parental rights in all but several extenuating circumstances. And it created the practice of concurrent permanency planning — simultaneously planning a foster child’s reunification with his or her natural family and (in case it failed) adoption by a foster parent. Many experts credit the law with helping to reduce the number of children in foster care from over half a million in 1997 to under 400,000 today.

The legislation, however, created or left unsolved several major challenges.

The first is that most research on foster care shows that children do better with their parents. This does not apply to cases of clear abuse or neglect. But where the decision to remove kids could go either way, the tie goes to the biological parent. Although the issue is not without debate, to take just one example, a study out of MIT found that children in foster care had 3 times higher arrest rates, twice the rate of teen pregnancies, and less job stability than similar children who returned to their family. The flipside of the ASFA legislation shortening the period of drift for foster children is that it reduces the window for parents to achieve a stable situation in which they can raise their kids.

The concurrent permanency planning model also comes with its own stresses, as it can pit the biological and adoptive parents against each other and leave foster children caught between two families.

This was the case for Steve and Erin — a couple profiled in To The End of June. They had one adopted child and decided to adopt another: a foster care baby named Oliver. His mother Caitlin had signed away her parental rights (on a napkin, but it was notarized) when the state took him. So Steve and Erin took Oliver home and spent a challenging but happy several month period integrating him into their family.

Before Steve and Erin could legally adopt Oliver, however, they heard from the foster care agency that Caitlin wanted Oliver back.

Caitlin had signed away her parental rights. But denying mothers the chance to raise their own children is not something courts like to do. It’s the “death penalty” of family court. Despite legislation like the Adoption and Safe Families Act, law professor Elizabeth Bartholet writes in Nobody’s Children that “Severing the birth parents’ rights and providing new parents for the child, has never been treated as a serious policy option… adoption has been seen as an arrangement suitable only for the truly exceptional situation.” Caitlin had a job at McDonalds and a more stable environment; she had the opportunity to make her case in court.

After several months of visits and indecision, Caitlin failed to appear at family court. The judge terminated her parental rights, and Oliver was spared another difficult break.

The problem is that no one knows in advance which parents will succeed in meeting their reunification plans and which will fail. ASFA legislation speeds up the process. But once parents lose their rights, children are up for adoption. And in the foster care system, a successful adoption is far from assured.

Broken Promises

“One new rule is, you have to honor the ten days. You can’t just drop a kid off at the agency anymore with a garbage bag all filled up with clothes.”

~ A parent advocate at a meeting for foster parents

Seeing children through the foster care system in orphanages or group homes until they reach adulthood may seem like a reasonably successful outcome. Grim, perhaps, and far from ideal. But realistic and minimally sufficient.

Attitudes like this, however, fail to appreciate the importance of a family or family member providing structure and always sticking with a child.

A number of studies track the experience of foster children who “age out” of the system without being adopted or reunited with their family. One pre-recession study put their unemployment rate (at age 24) at 40% — significantly worse than among other low-income youth. Their average monthly salary ranged from $450 in North Carolina to $690 in California. Foster kids who age out are twice as likely to lack a high school diploma or GED and 14 times less likely to complete college than the general population. Perhaps one third receive a mental health diagnosis like “major depression, anxiety, or substance abuse” within six years of leaving foster care. The rate of teenage pregnancies is 2.5 times higher among fostered women and the rate of incarceration for fostered men is 30%. Various studies have found that anywhere from 5-10% to above 30% of local homeless populations went through foster care.

The foster care system long ago changed to reflect the importance of family. Agencies have moved away from orphanages and try to place all children with a parent, although many foster children still live in group homes or institutions run by employees on rotating 8 hour shifts.

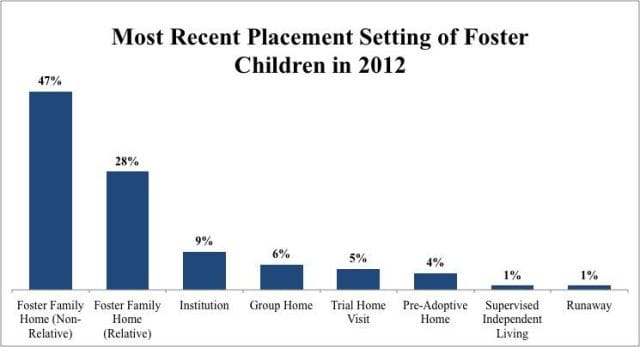

Data Source: Administration for Children and Families

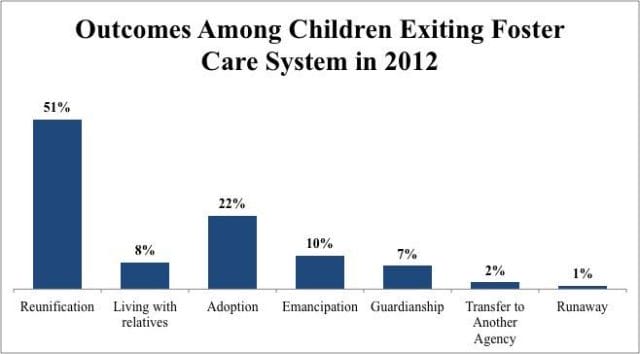

This is why the goal for all children is either reunification or adoption. Older children have the right to make emancipation their goal, but an increasing number of organizations focus on finding “forever families” for teenagers so that they will have the support of a family after they turn 18 or 21.

The problem is that the system all too rarely achieves the stable placements or final adoptions.

In 2012, the most recent year for which data is available, 397,122 children were in foster care. Over 50% of children who exited the system did so by reunifying with a biological parent. The median stay was just over a year and the average and median age of foster children between 8 and 9 years old.

Unfortunately, children who spend only a brief period in the system lead the averages to hide the many foster kids who spend years in limbo.

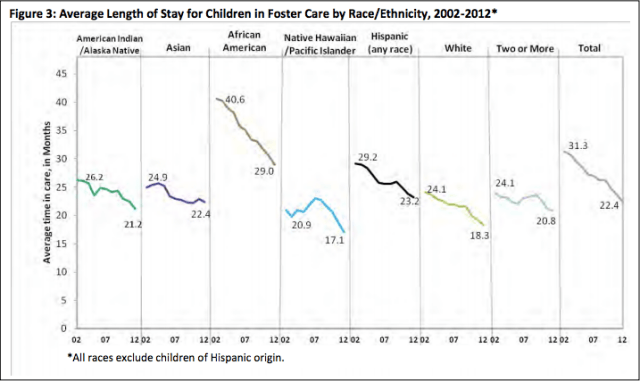

Over a quarter of all children in the system, some 100,000 kids, were waiting to be adopted in 2012. They spent an average of 34 months in foster care, with a median stay of over 2 years. And while 22% of children leaving foster care in 2012 did so through adoption, the number of adoptions plateaued around 50,000 per year beginning in 2002. A further 10% left by aging out of the system at age 18 or 21 and another 1% ran away, meaning that some 24,000 children left foster care without the support of any parents or family. They did so after spending closer to an average of 5 years in foster care. And while the total number of foster children has decreased, the number “aging out” has increased over the past decade.

Data Source: Administration for Children and Families

The unfortunate norm of the foster care experience is instability and low levels of care.

Anecdotally, the experience of foster children seems to be either very high or very low structure. Many children follow schedules with exact shower and eating times, with strict rules about staying inside. That’s true of many foster families, and especially of the group homes and institutions that account for 15% of foster kids. The other half are like Lei, a girl from Chinatown described in Beam’s book who was placed with Dominican parents who spoke very little English. The parents never spoke to Lei, but they fed her, gave her a bunk to sleep in alongside other children, and handed over her clothing stipend every month.

The high or low structure is not by itself good or bad. Beam describes Lei’s situation as a “basic, low-level functioning” that can seem “exemplary” given all the crises in foster care. One resident of a foster care home reflected in an Ask Me Anything that “Residents being abused, starved, etc. This does actually happen” and described his past in a foster home. The parents didn’t speak English and an older boy hit and kicked him. “Eventually I told someone and the cops ended up showing up,” he wrote. “But they left me there, with that boy.”

By official accounts, neglect and abuse are uncommon within the foster care system. Across every state, the Department of Health and Human Services (DHHS) finds that less than 1.7% of foster children experience abuse while in care. But anecdotally, foster kids often believe that over half experience abuse, and reports regularly condemn foster agencies’ inability to prevent abuse and oversee proper care. A number of investigations and studies find that the DHHS undercounts or fails to investigate properly.

Critics charge that the system often delivers minors to homes no better or even worse than the ones they left. Individual accounts range from malnourished children, to kids who are beaten or molested, to the prevalence of girls who fall victim to sex trafficking when pimps provide a more constant presence than their foster families.

The saddest aspect of learning about the foster care system is hearing stories of children who believe that neglect or abuse is the norm — or prefer it to moving. Beam writes of a girl named Tonya who stayed quiet about her foster mother beating her so that she could stay in one place until her mother could reclaim her. But her mother saw marks during a visit, so that night Tonya was moved to a new home. Seventy percent of foster children who spend 2 plus years in the system move between homes three or more times; Beam describes children who live in 10 or 20 different homes as “not unusual.”

Every night in every city, children are buckled into vans or police cars (like criminals), as wards of the state (like criminals), and driven to strangers’ houses and told to behave… Each move means another ruptured attachment, another break in trust, another experience of being unwanted or unloved.

~ Chris Beam in To The End of June

Foster parents and parents looking to adopt have the right to return foster children to an agency at almost any time. And many do. The majority of placements fail, even with capable, motivated parents, due to the challenges of fostering. Beam notes that foster children may misbehave and provoke their parents to maintain a sense of familiarity with their previous environment. Or misbehavior may be a continuation of a pattern developed in the previous home to try and control abuse by choosing when it takes place. Other foster children, used to being given up, may provoke their parents to see if the parents will still want them.

Parents looking to adopt suffer from a particular disconnect. The reasons they commonly cite for wanting to adopt are to offer their love, experience parenthood, or share activities. But many foster children aren’t ready to betray their biological parents by loving adoptive parents, or ready to connect with parents because they’re grieving from past hurts. Others are too jaded by being left on the curb to risk bonding with new parents.

While these disconnects explain some of the challenges of foster parenting, they alone do not justify why 100,000 foster kids are waiting for adoption. There is simply a shortfall of willing parents.

One culprit is a lack of information. As foster agencies don’t have large outreach budgets like foreign adoption agencies that charge thousands of dollars per placement, many Americans don’t realize that it’s possible to adopt a child from foster care. Among those parents that do know, a common fear is that foster children are irrevocably “broken.” Advocates push back against that perception, but the challenges are certainly real. “Please don’t be frustrated that you can’t ‘fix’ [foster kids] overnight from the hangups they are going to have forever,” one adopted, former foster child told an audience in an online discussion.

He also points to another constraint on adoptions as he describes himself as “a shelter puppy, rather than one from a breedist puppy mill” (an expensive adoption service). Race and age matter in adoptions: The stereotype that everyone wants white babies but not black teenagers holds some truth. Black and hispanic children spend noticeably more time in foster care, and over 20% of children waiting to be adopted are teenagers even though only 5% enter foster care as a teen and the average age of entry into the system is between 4 and 5.

Potential adoptive parents are also pushed away by one of the great paradoxes of the foster care system: Even as caseworkers desperately need adoptive parents, in the parenting classes required to become certified foster parents or adopt a foster child, the teachers recommend that parents don’t get too attached. Foster care, they say, is a temporary solution until the children’s biological parents can take care of them once again.

Despite all the concurrent permanency planning and legislation to hasten a decision on foster children’s final status, as the case of baby Oliver (described above) demonstrates, there is always uncertainty. But that makes it difficult to operate as essentially the nation’s largest adoption agency.

In It For the Money

I cannot believe how many people have said to me, “Yeah, but you wouldn’t do it if you weren’t getting paid.” Seriously, so many people have said that aloud. It basically comes down to $600 a child. Any child over 8 is going to run you deficit. Every single teenager we’ve had has cost us more than we’ve received. Every. Single. One. So get that out of your head, America. It is not worth the money to be a foster parent for profit.

~ A foster parent of 5 years in a middle class family

The foster care system relies on the charity of American individuals and families. But to make fostering or adopting less of a burden, the government enrolls foster children in Medicaid and offers families a stipend to cover living expenses. This has led to the perception that foster families are in it for the money.

Foster Family Home basic (reimbursement) rate in California, effective July 2012. Rates are monthly. Data source: California Department of Social Services

The stipends are not much, and insiders often deny a profit motive. Still, as Beam points out, money does seem to motivate at least some parents, as many foster parents’ incomes are “close to or below the poverty line.” In addition, one survey found that the majority of foster kids are in homes fostering 5 or more minors. This suggests that some very giving, altruistic individuals are foster care workhorses, but also that a single mother supplementing welfare checks by caring for foster kids may be typical.

It’s unclear whether money serving as a motivator is a problem.

Paying foster parents (or adoptive parents) more than the cost of expenses feels uncomfortable. But when kids like Lei, who lived for 5 years in a home with parents who didn’t speak her language, are considered almost a success story, it may be time to rethink that notion.

Offering more money could shrink the adoption deficit and, with the right conditions, lead to fewer foster children being dropped off at the curb of foster care agencies. A number of altruistic foster parents interviewed by Beam praised the idea as recognizing their hard work. The prospect of profit would not be without problems, but done right, it could improve foster care.

In the meantime, it seems worth exploring whether caseworkers could serve as a constant in their charges’ lives. Given the reality that many foster kids move homes 2 or 3 or even 10 or 20 times, many lack any constant presence in their life. The system may pass their file between caseworkers just as often. Some social workers go above and beyond to serve as mentors to foster kids. The government doesn’t want to play nanny, but as the system doesn’t deliver the dream scenario of a caring foster parent to every child, it may warrant owning up to the responsibility of playing parent to the wards of the state.

A Question of Incentives

A single perverse incentive runs through the foster care system: foster care agencies’ funding is dependent on the number of foster children they manage. If every foster child is adopted, the flow of government dollars stops flowing.

At its worst, this would mean that agencies have an incentive to take children away from their parents, even when it’s unnecessary. This may happen in marginal cases, and the perception certainly exists among some parents that agencies are out to get their kids. Still, overburdened caseworkers have an equally strong incentive to keep cases from accumulating. But it does mean that foster care, like a fee for service health care system, spends its money on treatment and tracking financials rather than on prevention.

A lawyer working with New York City’s Administration for Children’s Services (ACS) notes that social workers spend much of their time keeping track of the services they deliver, often using complicated classification schemes, so that foster agencies can bill for them. As caseworkers do all this paperwork, in his words, “Half of what ACS does is counting beans.”

Meanwhile, the model of funding foster agencies on a per foster child basis, while logical, can lead to absurd outcomes. If a mother lacks the financial means to feed her baby, for example, a social worker may decide that he needs to remove the baby from the home. The state would then pay a foster family a stipend for the cost of caring for the baby. Foster agencies could not simply pay that money to the mother so that she could feed her baby herself. Federal legislation requires that states make “reasonable efforts” to help children stay with their natural parents when it is safe to do so. But the flow of funding is to children in foster care, not children at risk of needing it.

We can see the impact of this incentive system through the example of Florida, which in 2006 became the first state to accept a set amount of funding instead of a per diem setup. Thanks to the block grant, agencies can spend money (and time) on families to prevent them from needing foster care in the first place. In 2009, the New York Times chronicled the case of Sylvia Kimble. She faced the prospect of caring for 6 grandchildren when her daughter and daughter-in-law were arrested. In most states, most of the children would have entered foster care. But the Florida agency “provided in-home counseling, therapy for the children and cash aid to help the makeshift family stay intact and even thrive.”

Having caseworkers work to prevent the entrance of children into Florida’s foster care system now works in synergy with agencies’ financials. They also have the time to do so because they don’t spend all their time tracking services. While not without critics, the change has so far received accolades for decreasing the number of children in foster care by over 10,000.

State of the Union

When national legislation on foster care is discussed, observers describe it as a pendulum.

One legislative push will focus on the rights of children. It usually follows a media story about a foster child (most likely a white girl) returned to a biological parent who killed or horribly abused the child. These bills, like Clinton’s Adoption and Safe Families Act, instruct judges to put more scrutiny on biological parents and to facilitate adoptions.

The next policy push will focus on the rights of parents. It cites the findings that children generally do better with their biological parents, and it highlights cases when parents striving to raise their kids well have their parental rights terminated by a foster care system that pushes adoptions.

As the pendulum swings back and forth between the two positions, there is little day-to-day pressure to keep foster agencies, judges, and state investigators performing adequately. Foster care has individual champions, from exemplary foster parents and caseworkers to scholars and the rare politician who prioritizes the issue. But as foster kids have neither the ability to vote nor resources, their political impotence is hard to overstate. The expression of their voices is usually dependent on the publication of tear-jerk media stories.

If we were to make a modest proposal, we would suggest that the president of the United States begin each State of the Union address with a reflection on the foster care system. As observed by Cris Beam in To The End of June (a book we recommend and on which this primer drew heavily), foster care does not need to be fixed directly to improve child welfare. “Anything that touches social reform,” she writes, “touches foster care too.” Individual choices lead to children landing in foster care. But on a macro level, it results from social failings. Any action that reduces poverty, improves healthcare (especially access and mental health treatment), or makes drug policy more sane will reduce the strain on the foster care system. And the state of foster care, and the children in its charge, will represent that progress, and how well the country serves its most vulnerable citizens.

This post was written by Alex Mayyasi. Follow him on Twitter here or Google Plus. To get occasional notifications when we write blog posts, sign up for our email list.