For most Americans, 1973 was marred by shortages. In the year’s first few months, the stock market crashed and lost over 45% of its value — one of the worst declines in history. In October, an Arab oil embargo sparked an ongoing crisis that saw gas rise from $3 per barrel to nearly $12 per barrel. Quietly, the U.S. spiraled into a period of economic stagnation and malaise it hadn’t seen since the Great Depression (albeit, much less serious).

Gasoline, electricity, and onions were heavily reported as goods and services that were in limited supply, and Americans cultivated a “shortage psychology.” Then, right in the midst of this economic turmoil, a toilet paper scare ignited a communal panic attack. Perhaps the most memorable shortage in a decade of shortages, it involved government officials, a famous television personality, a respected congressman, droves of reporters, and industrial executives — but it was the consumers themselves who were ultimately blamed.

Like most scares, the toilet paper fiasco all started with an unsubstantiated rumor. In November of 1973, several news agencies reported a tissue shortage in Japan. Initially, the release went unnoticed and nobody seemed to put much stock in it — save for one Harold V. Froelich. Froelich, a 41-year-old Republican congressman, presided over a heavily-forested district in Wisconsin and had recently been receiving complaints from constituents about a reduced stream of pulp paper. On November 16th, he released his own press statement — “The Government Printing Office is facing a serious shortage of paper” — to little fanfare.

However, a few weeks later, Froelich uncovered a document that indicated the government’s National Buying Center had fallen far short of securing bids to provide toilet paper for its troops and bureaucrats. On December 11, he issued another, more serious press release:

“The U.S. may face a serious shortage of toilet paper within a few months…we hope we don’t have to ration toilet tissue…a toilet paper shortage is no laughing matter. It is a problem that will potentially touch every American.”

In the climate of shortages, oil scares, and economic duress, Froelich’s claim was absorbed without an iota of doubt, and the media ran wild with it. Wire services, radio hosts, and international correspondents all sensationalized the story; words like “may” and “potentially” were lost in translation, and the shortage was reported as a doomed truth. Television stations aired footage from the Scott Paper Company — one of the ten largest producers in the U.S. — of toilet paper rolls shooting off the production line.

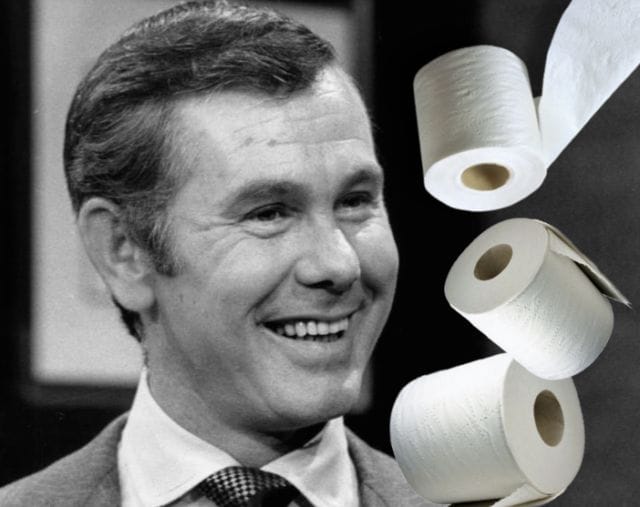

The ground had been set for a consumer panic; all it needed was a spark to ignite it. When Johnny Carson cracked a joke about toilet paper on his television talk show, things got serious. “You know, we’ve got all sorts of shortages these days,” he told 20 million viewers. “But have you heard the latest? I’m not kidding. I saw it in the papers. There’s a shortage of toilet paper!”

Absolute madness ensued. Millions of Americans swarmed grocery outlets and hoarded all the toilet paper they could get their hands on. “I heard it on the news, so I brought 15 extra rolls,” one customer told The New York Times. “For my baby shower,” said another, “I told my party guests to bring toilet paper.” In the chaos, company officers and industry leaders told the public to remain calm; store owners ordered astronomical quantities of toilet paper, and set limits of two rolls per customer. Nobody seemed to play by the rules.

“If people wouldn’t hoard and get so excited about this, everything would be okay,” a supermarket executive told the St. Petersburg Times. He subsequently increased his toilet paper from 39 cents to 69 per roll, but customers still cleared his shelves each day. Merchandisers struggled to re-stock supplies, as the boxcars they relied on for shipments were in high demand by thousands of other stores.

For four long months, toilet paper was a rare commodity. It was bartered and traded, and a black market even emerged before the whole ordeal subsided in February of 1974. Slowly but surely, the American public realized that there had never been a shortage to begin with: rather, it had been artificially created by a pop culture frenzy.

In the aftermath, Johnny Carson received the brunt of the blame for propagating the shortage myth and issued a rather serious apology on his comedy talk show. “I dont want to be remembered as the man who created a false toilet paper scare,” he told viewers, directly facing the camera. “I just picked up the item from the paper and enlarged it somewhat…there is no shortage.” (Unfortunately, it wouldn’t be his last run-in with the toilet industry: in 1976, he was embroiled in a lawsuit with a porta-potty company named “Here’s Johnny.”)

As for an explanation of what induced such panic, marketing professor Steuart Britt later enumerated on a theory, which is probably more relevant than ever in today’s digital age:

“Everybody likes to be the first to know something. It’s the did-you-hear-that syndrome. In the old days, a rumor took a long time to spread — enough time to let people discover its validity. Now all it takes is one TV personality to joke about it.”

Last year, the Venezuelan government faced a similar crisis. When reports surfaced that the government’s price controls may lead to a lack of toilet paper, citizens panicked and induced a shortage. In Caracas, the country’s capital, lines flowed down the streets when new shipments of rolls came in. The situation got so out of hand that President Jorge Arreaza occupied a toilet paper factory, and issued a statement eerily reminiscent of America’s situation in 1983. “[We] will not allow hoarding or failures in the production and distribution of essential commodities,” he said. “There is no deficiency in production.”

This post was written by Zachary Crockett. Follow him on Twitter here, or Google Plus here.