In 2011, a blue collar worker with an aching back consulted a specialist in Oklahoma City. The specialist told him that he would need surgery to have a stimulator placed in his back. Writing for TIME, Steven Brill referred to the patient as Steve H. As he had health insurance through his union, and the operation would not even require an overnight stay, Steve H. was not worried.

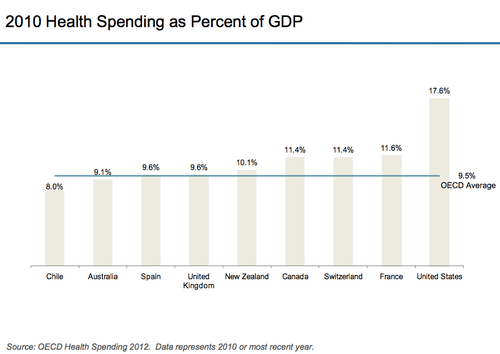

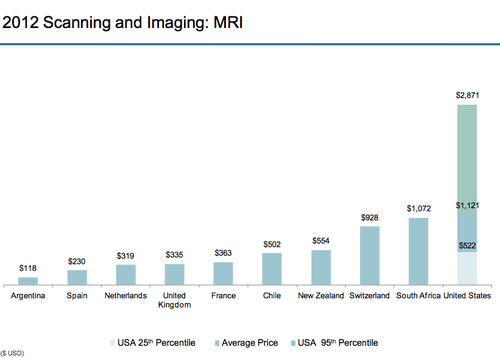

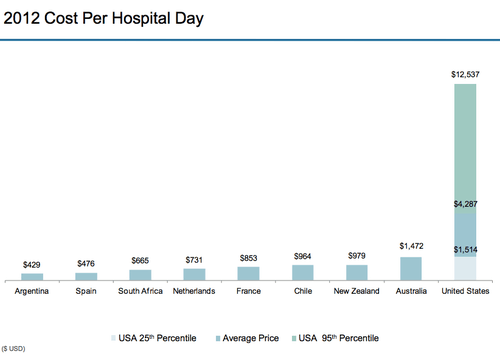

It’s hard to overstate the importance of having health insurance in the United States. America spends more on healthcare than any other country both in absolute terms and on a per person basis. As shown in several graphs below, many procedures dependably cost from double to an order of magnitude more in the US than in other developed countries. The royal birth infamously cost less than the average delivery in an American hospital.

Source: International Federation of Health Plans

At the same time, Americans are vulnerable to even small, unexpected expenses. It’s not news that a repressed economy and persistent unemployment has left Americans facing diminished incomes and tough financial choices. What may be surprising, however, is that some 50% of Americans “say that they definitely or probably couldn’t come up with $2,000 in 30 days.”

This statistic, reported by the Wall Street Journal, comes from a research paper published by the National Bureau of Economic Research. The research is dated as it used data from a 2009 survey and was published in 2011. But even a marked improvement would leave a large percentage of Americans in a state of financial fragility. The Journal notes that when asked about their ability to pay an unexpected $2,000 bill, “24.9% of respondents reported being certainly able, 25.1% probably able, 22.2% probably unable and 27.9% certainly unable.”

After his surgery, Steve H. received the type of news that few Americans can afford to face – a large medical bill. The total cost of his operation came to $86,951. Due to his insurance plan’s annual limit of $60,000 and prior medical expenses, Steve H.’s insurance would leave him to pay over $40,000 himself.

Was the cost of Steve H.’s surgery justifiable? In search of answers about high healthcare costs for his TIME article “Bitter Pill: Why Medical Bills are Killing Us” (paywall), Steven Brill discovered the chargemaster – the “internal price list” maintained by each hospital that details the cost of everything from Aspirin to brain surgery.

Brill had seen hospital bills charging patients $39 for wearing a hospital gown and $31 for the strap used to keep them still during surgery. To check the prices of more opaque charges like niche medications and a doctor’s time, he checked hospitals’ chargemasters against the prices billed to Medicare. Why? Brill notes:

Seeing what Medicare would [pay] shines a bright light on the role the chargemaster plays in our national medical crisis… That’s because Medicare collects troves of data on what every type of treatment, test and other service costs hospitals to deliver. Medicare takes seriously the notion that nonprofit hospitals should be paid for all their costs but actually be nonprofit after their calculation. Thus, under the law, Medicare is supposed to reimburse hospitals for any given service, factoring in not only direct costs but also allocated expenses such as overhead, capital expenses, executive salaries, insurance, differences in regional costs of living and even the education of medical students.

Brill found that the chargemaster frequently charged ten times Medicare prices for inexpensive supplies like over the counter drugs or even services costing thousands of dollars. Five and six figure products and services were often two to ten times the cost of Medicare prices. In Steven H.’s case, the hospital charged him $49,237 for the stimulator implanted in his back. The device sold wholesale for $19,000.

Hospital administrators shrugged off Brill’s questions about chargemaster prices, suggesting that they were irrelevant – a starting point for negotiations with insurance companies that no one actually pays.

But some people do pay chargemaster rates. The 48.6 million Americans without health insurance must pay those rates when and if they go to the hospital. And Americans (like Steve H.) whose insurance has seemingly large or insurmountable annual or lifetime limits pay chargemaster rates when they exceed them.

Priceonomics has yet to locate data on the number of Americans facing annual limits on their insurance, but a (dated) poll found that 55% of Americans with insurance faced lifetime limits. One third had limits of $2 million or more and 22% between $1 and $2 million. A more recent government study found that 105 million Americans face lifetime caps on their insurance coverage.

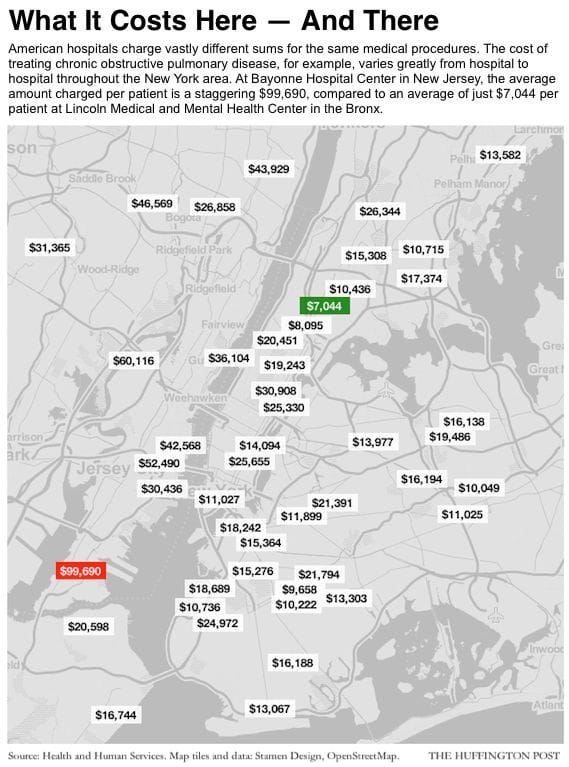

Americans rarely see chargemaster prices, but doing so reveals how little market forces operate in America’s private sector healthcare industry. Brill writes of the chargemaster that “there seems to be no process, no rationale, behind the core document that is the basis for hundreds of billions of dollars in health care bills.” The assertion is illustrated visually by the below map showing the price of a medical procedure (in this case for chronic obstructive pulmonary disease) at different Manhattan hospitals.

Source: Huffington Post

The Patient Protection and Affordable Care Act (aka Obamacare) largely bans insurance caps in new plans and will phase out existing caps over the next several years. But chargemaster prices will remain relevant for people with insurance as well as those without. Brill writes:

Insurers with the most leverage, because they have the most customers to offer a hospital that needs patients, will try to negotiate prices 30% to 50% above the Medicare rates rather than discounts off the skyhigh chargemaster rates. But insurers are increasingly losing leverage because hospitals are consolidating by buying doctors’ practices and even rival hospitals. In that situation — in which the insurer needs the hospital more than the hospital needs the insurer — the pricing negotiation will be over discounts that work down from the chargemaster prices rather than up from what Medicare would pay. Getting a 50% or even 60% discount off the chargemaster price of an item that costs $13 and lists for $199.50 is still no bargain. “We hate to negotiate off of the chargemaster, but we have to do it a lot now,” says Edward Wardell, a lawyer for the giant health insurance provider Aetna Inc.

Brill covers the experience of several patients who faced astronomical healthcare debts due to inadequate insurance and their success in dealing with their debt varied widely. He notes that most patients don’t “know that hospital billing people consider the chargemaster to be an opening bid” rather than a set price. Patients smart or lucky enough to find someone in the business of negotiating down hospital bills reduced their bills by tens or hundreds of thousands of dollars. As nonprofits, hospitals could also charitably reduce bills for those unable to pay. Some did, but the majority granted only minimal concessions or simply sold off the debts to debt collectors.

The picture drawn by Brill’s long look at healthcare is that of an industry about as rational, predictible, and fair as a lottery:

Unless you are protected by Medicare, the health care market is not a market at all. It’s a crapshoot. People fare differently according to circumstances they can neither control nor predict. They may have no insurance. They may have insurance, but their employer chooses their insurance plan and it may have a payout limit or not cover a drug or treatment they need. They may or may not be old enough to be on Medicare or, given the different standards of the 50 states, be poor enough to be on Medicaid. If they’re not protected by Medicare or they’re protected only partly by private insurance with high copays, they have little visibility into pricing, let alone control of it. They have little choice of hospitals or the services they are billed for, even if they somehow know the prices before they get billed for the services. They have no idea what their bills mean, and those who maintain the chargemasters couldn’t explain them if they wanted to. How much of the bills they end up paying may depend on the generosity of the hospital or on whether they happen to get the help of a billing advocate. They have no choice of the drugs that they have to buy or the lab tests or CT scans that they have to get, and they would not know what to do if they did have a choice. They are powerless buyers in a seller’s market.

Healthcare is a lottery that almost everyone is eligible for – patient advocates report that their clients are often middle or upper class people who never believed they could face crippling medical bills – but as the data on Americans’ financial fragility shows, almost no one is prepared for. The elimination of most caps on insurance by Obamacare may protect Americans from the terrible debts described above. But it can’t disguise the fundamental problem that costs are not just high, but set without any rational basis.

This post was written by Alex Mayyasi. Follow him on Twitter here or Google Plus. To get occasional notifications when we write blog posts, sign up for our email list.