Photo: Cosmic Kid

There was always something different about Scott Rella. A New York City kid who perennially had trouble sitting still, he took more interest in “hands-on” endeavors than school, and dropped out before completing his GED. He pursued the culinary arts and he eventually became a chef at the Waldorf-Astoria, the city’s most revered hotel.

A few months into the job, Rella’s boss asked him to sculpt an ice centerpiece for an upcoming banquet. He was handed a set of expensive Japanese chisels and handsaws, and huge blocks of ice were wheeled in. “Let’s see what you can do,” the head chef told him.

Rella enjoyed himself so much that he decided to carve his way into a new industry: in 1981, he started “America’s first ice sculpture company.” With corporate and event connections he’d made at the Waldorf, he proceeded to build his enterprise “into a monster:” in the following years, Rella would craft masterpieces for famous galleries, movie premieres, and celebrity weddings.

Today, a select handful of people make a living as ice sculptors. Using $1,700 chainsaws, a bevy of hand tools, and CNC machines, they craft mind-boggling works of art from 300-pound blocks of ice. The trade requires strength, endurance, and an engineering skill-set, as well as artistic talent.

How did ice sculpting become a burgeoning industry, who are the artists at its helm, and how do the economics of the industry work?

A Brief History of Ice Sculptures

Historically, the uses of ice have been well-documented. Nearly 4,000 years ago, Inuits in present-day Alaska and Canada harvested ice from frozen lakes to build insulated shelters (igloos). Written records dating back to 600 BC clarify that farmers in the highlands of China orchestrated controlled floods, froze the water into ice, and used it to preserve perishable foods. The artistic and functional sculpting of ice is believed to have also begun in China, centuries later.

In the 1600s, native fishermen in the province of Heilongjiang carved “ice lanterns” to guide them through dark winter terrain: they’d freeze buckets of water, carve a hole in them, and insert candles that would illuminate the ice. The trend spread throughout northeastern China, and ice became a popular medium for outdoor lighting.

In 1740, Russian empress Anna Ivanovna, who had a malicious sense of humor, ordered an ice palace to be constructed. She then proceeded to force Prince Mikhail Golitsyn into wedlock with “an exceptionally ugly servant,” and ensured that the “fur-laden” couple were locked within the frozen mansion’s confines for the night.

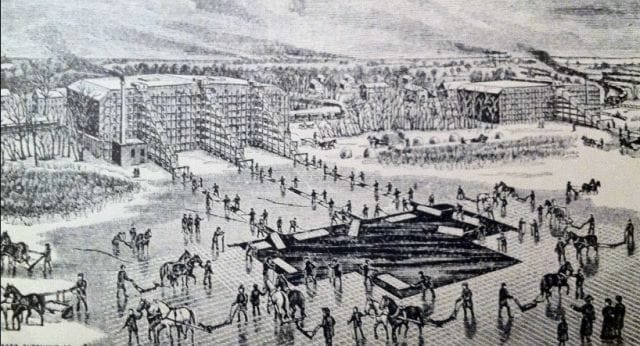

Valery Jacobi’s Ice House, depicting Anna Ivanovna’s palace (1878)

Throughout the 1800s, the demand for ice increased, especially in places where it didn’t naturally exist year-round; inventors gradually began to capitalize. In 1834, the first ice machine was patented in Britain, using ether to expedite the freezing process; ammonia soon replaced ether, and air bubbling systems were integrated to produce crystal-clear ice for carving. By 1920, 750,000 giant blocks of ice were made every day in the United States.

The first application of ice as an art medium is believed to have been in 1892, when renowned French chef Auguste Escoffier created an ice sculpture of a swan to accompany a new dessert he made. This began a long-standing tradition of ice sculpting in the culinary arts; many ice sculptors today are introduced to it in culinary school.

During the 1980s, ice increasingly rose to prominence as an art medium in the United States, and an entire industry spawned around it. In 1987, the National Ice Carving Association (NICA) was formed to “promote ice sculpting as an art form;” a year later, ice sculpting became a Cultural Olympiad event at the Olympics.

The Icy Road to Success

Photo: Julien Ricard

Like Scott Rella, most ice sculptors find their way into the business via culinary school, where fruit, vegetable, and ice carvings have long been used to decorate banquets. Stephan Koch, owner of ice sculpting company Indiana Ice Studio, recalls being introduced to ice through food:

“I first got into ice sculpting when I learned in a Garde Manger class at Culinary school. Ice sculpting started out as a way to garnish the buffet or food table just like butter carving, or tallow carving or vegetable carving or cheese carving.”

For the course of its life, ice sculpting was relegated to this niche community. But after envisioning a separate market for ice sculpture, Rella broke off in 1981 and started his own project. A tenacious self-promoter, Rella used his connections in the food industry to market his skills. With no competition, his business grew to unimaginable heights.

“I made more money doing this than I did as a chef in New York City,” recalls Rella. “And I worked at one of the best French restaurants in the country.” By 1983, he was making 225 sculptures a week, and was pulling in $1.5 million a year in profit.

Photo: Bill Jacomet

His successes encouraged others to join the industry: by 1985, there were over 50 ice sculpting companies in operation, as well as competitions, fine art exhibits, and corporate-commissioned work.

Corporate Ice and the Rise of Technology

In the early days, most sculptures were made entirely by hand, employing the use of chainsaws, chisels, and other hand-tools. “Chainsaws do about half the work,” says Koch, “then we finish with specialty die grinder bits, grinders, and sanders.”

Typically, an ice sculptor started with a standard block of ice (40”x20”x10”), drew out his design on paper, traced it onto the ice, and spent “15-20 minutes chainsawing the stuff off that didn’t need to be there” before detailing it. In the last decade, specialized CNC ice machines have been introduced. The machines, which are operated using computer programs, quickly cut out logos and figures with unbridled precision, and have completely changed the industry.

A look at how most commercial ice sculptures are made today.

Steve Cox is a self-proclaimed “dinosaur in the world of ice carvers.” For nearly 30 years, he’s owned and operated Creative Ice, a company which sells sculptures for corporate events, weddings, and bat mitzvahs, and also plays a hand in the “artisan ice business” — high-quality ice cubes that run anywhere from $1 to $10 per cube.

Cox is one of the few ice distributors approved by Department of Agriculture to produce food grade drink ice.

Specialized ice cubes (Creative Ice)

His company offers hundreds of custom sculptures — from $350 eagles to $1,400, five-foot tall elephants. Some of his stranger designs include stiletto luges, flying pigs, and dump trucks.

Because of the high volume of work his studio receives — as many as 15-20 sculptures per week — Cox relies on a CNC router and other electric tools to help scale the process. An average sculpture takes 45 minutes to two hours to program, cut, and detail, and pays $300-600.

While the use of CNC machines has been hotly debated in the ice sculpting community (especially by “the purists”), Cox says they’re used by almost everyone now.

A CNC router designed for ice carving; Image via iceguru.com

Julian Bayley was the first to use CNC machines for ice sculpting, and has played a major role in advancing technologies in the business.

Twenty-eight years ago, Bayley left a job in advertising to start Ice Culture, a company that provides commercial sculptures and also sells ice blocks and machinery to other businesses. Today, they operate out of a 50,000 square foot plant, and have sold specialized equipment in 58 countries.

Bayley sells specially equipped CNC machines to other ice businesses for about $50,000 each; he’s also sold 363 lathes at $10,000 a pop. Despite rising freight costs, his ice block business thrives too: the company produces 100 blocks per day (using a $15,000 Clinebell machine), which can be sold at up to $100 each (though in bulk, prices may drop to around $35 each). When NASA needed aerospace-grade ice to test space shuttle components, they turned to Bayley and Ice Culture.

In fact, companies and carvers from around the world visit the Ontario plant, and for good reason: Bayley has gained a reputation in the business for utilizing new technologies to create unimaginable works out of ice.

Last year, Bayley and his team built a truck out of ice for a Canadian Tire commercial. The final product weighed eleven thousand pounds, set a Guinness World Record as the “first propelled ice creation to drive,” and garnered attention from every media outlet imaginable. “In all my advertising years, I’d never seen anything get so much publicity,” laughs Bayley. “People from all over the world were calling us.”

This wasn’t the first time Bayley’s ice stunts had landed him in the spotlight. Disney once hired him to build “a giant ice castle” in Times Square, which required 2.5 tons of ice, and a 60-foot crane:

“They were promoting a program on fleeting, magical moments, and wanted this magnificent sculpture that would be gone in a matter of hours. We were in Times Square by 11pm, assembled the castle, and by 11am the following morning we had to have it finished for Good Morning America.”

Ice Culture has several other revenue streams. They’ve capitalized on the “ice lounge” boom, building specialized ice clubs and bars across the world on $100-200,000 contracts. The company also sees an occasional banquet or event that racks up quite a bill: “One Brazilian wedding on Long Island ordered close to $100,000 in ice,” says Bayley.

An ice lounge; photo courtesy of Julian Bayley

Specialized CNC and lathe technology has made these types of large-scale projects more manageable, and machinery continues to evolve in the ice world. Bayley tells us the newest trend is robots, which are slowly replacing CNC machines as a long-term way to scale production. “They’re fairly affordable,” he says, “and there’s a good used market.”

But others say the advancements in production have come at the expense of unique creations and true art. “All the new technology has made the industry more accessible to businessmen, and people who don’t necessarily care for the artistic aspects,” one carver tells us. “That’s why a lot of us in the community rely on other outlets like competitions and live shows. It’s just you, the ice, and a chainsaw.”

Live Performance

Photo: Bill Jacomet

In 1996, Scott Rella sold his successful ice sculpture company and proceeded to create another industry. With two friends, he started Fear No Ice, an ice performance company that offers live shows. For two years, it faltered and Rella saw no dividends; then, with a little luck, it took off and “become a global entity.” He’s since traveled around the world with the group, putting on shows in places like Dubai, Australia, and Bahrain.

“I’m lucky,” says Rella. “I worked hard and a lot of things fell my way. I didn’t sit back and invent them — I didn’t think these ideas up out of the clear blue sky: most of them fell in my lap, and I ran with them.”

Rella’s success with Fear No Ice spawned a lucrative ice performance industry.

Venezuelan master carver Max Zuleta operates Ice Beat Factory, a troupe that combines live music, chainsaws, and ice art:

“Master Carver Zuleta transfixes audiences as he transforms hundreds of pounds of incandescent ice into brilliant sculpture live on stage to the backdrop of dazzling light show visuals and the beat of exotic and modern instrumentations. This industrial, tech-savvy production has all the unexpected twists and turns of a circus including the acrobatic antics of a Cirque-style clown!”

According to a source in the business, Zuleta can command as much as $20-30,000 per show. Like Fear No Ice, Ice Beat Factory tours around the world and caters to corporate events.

The Chainsaw Chicks, an all-female ice performance group, follows the same business model. Dominque Colell, the group’s front-woman, got her start in ice sculpting as a Miss America beauty pageant contestant. “My dad suggested ice carving as my performance for Miss Ventura County,” she says. “I ended up doing it and winning.”

Photo: J.Massey

She’s since made a career of it, and has amassed a collection of 13 chainsaws — all of which serve a different purpose during her performances with The Chainsaw Chicks. The group has toured internationally, appearing on numerous television programs and even opened a show for rock group Hootie and Blowfish.

“It’s kind of a big part of where the ice carving industry is heading,” one performer tells us. “It’s getting harder and more competitive to make a living selling sculptures — the business is so big. This is a way for us to just appeal to a completely different market.”

Competitions

Photo: Greentxjumper

Today, a number of competitions exist for ice carving, the most notable of which are NICA’s National Championships, and the World Ice Art Championships. Neither are particularly lucrative — a first place victory at the latter pays $6,840 — but each comes with prestige and can boost sculpture sales for the victor.

The world championships, held in Alaska during the last week of February, hosts 150 sculptors from around the world and sees more than 45,000 spectators. Competition consists of two categories: single block (a team of two works with one 3’x5’x8’ block), and multi-block (a team of four works with ten 6’x4’x3’ blocks — each weighing 4,000 pounds). Power tools (chainsaws, drills, dremels) and scaffolding are employed, and the carving process can take over a week.

In the competitive ice sculpting world, Mark Daukas is a legend — an irrefutable ice king. “He’s the Michael Jordan of our community,” says one carver. “We used to call him the Lance Armstrong of ice carving…I wouldn’t be surprised if Mark was doping too. That’s just how good he is.”

Daukas is the only sculptor to win three consecutive National Championships in a row (1991-1993), and has won six total (which netted him only about $2,000 each). Of the 52 ice competitions he’s entered over the course of his career, he’s won 45 — an 87% win percentage. Add to this a World Championship title, and it’s clear why the man is so revered.

His competition pieces have included a 15-foot replica of the Statue of Liberty, a seven-foot Empire State Building (complete with King Kong), and an eight-foot saber-toothed tiger making its way down a precarious cliff.

Today, Daukas doesn’t compete much anymore and a new “king” has taken the throne. Junichi Nakamura hails from Japan, and grew up greatly influenced by the sculptures of Harbin, China, a city with a rich history of ice carving. (Each January, Harbin turns into an icy wonderland for its International Ice and Snow Sculpture Festival and whole ice cities are erected; it’s been informally referred to as a “wonder of the world.”)

In recent years, Nakamura has won 10 out of 14 World Ice Art titles he’s competed in. Other artists attribute his success partly to his “willingness to take risks that other sculptors can’t stomach.” During a competition in 2005, Nakamura performed a risky final maneuver on his masterpiece and was nearly crushed to death by 10,000 pounds of ice:

Another time, one of his sculptures collapsed in the final stages of judging when somebody was clearing the ground around it with a leafblower. Nakamura has taken advantage of the freedom the competition scene affords artists — a freedom that they may not be exercised in everyday commercial work.

But Nakamura also has a lucrative side business, selling instructional books and custom-made tools that go for as much as $3,300 for a handsaw.

Other competitors have made a living selling custom-made tools as well.

Steve and Heather Brice, an Alaskan couple who build their sculptures in a studio made of ice. Inside their 20-degree Fahrenheit space, tables, chairs, and workbenches all constructed of ice, and handmade tools adorn the walls.

Courtesy, Brice and Brice Ice Sculptures

The couple, who have won a combined 23 World Championship titles, also harvest their own ice from local lakes, and operate The Aurora Ice Museum, an “ice hotel” featuring “life size jousters on horseback, a polar bear bedroom, a Christmas tree bedroom, a kid’s snowball 2 story fort, an igloo and an ice outhouse.”

But for most ice sculptors, competitions don’t pay much; the majority say that 85-90% of their business is still commercial.

A Fleeting Art Form

Photo: Valida

For an ice sculptor, accepting the impermanence of of art is especially important. In most cases, a sculpture lasts only six to eight hours at room temperature before losing definition and reverting to its core elements.

Stephan Koch, owner of Indiana Ice Studio, doesn’t think his art form is particularly unique in its fleeting brilliance:

“It’s done all the time with flowers, food, and drink. Ice sculpture like other ephemeral arts are designed to last for a particular length of time. If they last as intended our goal is accomplished. All artwork is impermanent — it’s just that ice sculpture has a particularly short life.”

“Besides,” he adds, “if my ice sculptures never melted, no one would want to buy another one.” His point is valid — the very nature of his artwork is what keeps his customers coming back for more.

For others, like Heather Brice, the transient property of ice is what makes it definitively special a a medium:

“Ice has a kinetic energy — it gives you the ability to really make a piece of artwork sing. When it’s clean and pristine, ice can take on a life of it’s own. It’s temporal — you have to enjoy it in the moment.”

This post was written by Zachary Crockett. Follow him on Twitter here, or Google Plus here.