They stain tongues green, red, and blue; they send blood sugar levels on Odyssean voyages; they induce brain-freezes that crumble even the most stoic men.

Every year, 7,290,000 gallons of Slurpee are consumed worldwide — enough to fill 12 Olympic-size pools. The beverage — essentially frozen, flavored sugar water blasted with carbon dioxide — comes in an unending flow of flavors and especially entices its suitors during the summer months.

But the icy treat has an intriguing history: it was discovered accidentally, became a staple of “cool kid” culture in the 60s and 70s, and has continued to thrive thanks to brilliant marketing (and occasional deliciousness).

ICEE: The Slurpee’s Predecessor

In 1958, a Dairy Queen owner in Kansas inadvertently started what would become a beverage empire.

Omar Knedlik was an unlikely inventor: he grew up poor, fought in World War II, and subsequently purchased a few ice cream shops with his military pay. He did well for a while, but when a series of poor hotel investments whittled his finances, he cashed out, moved to Kansas, and took over a Dairy Queen.

Knedlik’s franchise didn’t have a soda fountain, so he began placing shipments of bottled soda in his freezer to keep them cool. On one occasion, he left the sodas in a little too long, and had to apologetically serve them to his customers half-frozen; they were immensely popular.

When people began to show up demanding the beverages, Knedlik realized he had to find a way to scale, and formulated plans to build a machine that could help him do so. He reached out to The John E. Mitchell Company — a Dallas-based outfit that had previously made cotton cleaning equipment, but had “pivoted” into selling aftermarket automobile air conditioners. The company developed an interest in becoming an original equipment manufacturer (OEM), and agreed to help Knedlik with his vision.

Five years of trial and error ensued, resulting in a contraption that utilized an automobile air conditioning unit to replicate a slushy consistency. The machine featured a separate spout for each flavor (only two at this point), and a “tumbler” which constantly rotated the contents to keep them from becoming a frozen block.

ICEE’s polas bear; Source: Steve Snodgrass

Initially, Knedlik thought to name his product “scoldasice” but when an ad-man friend persuaded him otherwise, he hired a young local artist, Ruth E. Taylor, to do branding.

Taylor coined the “ICEE” name, and drew up a mock sketch of the iconic original logo — four letters placed in blue and red boxes, adorned with ice (a feature that has remained unchanged today). She also conceived the idea to use a polar bear, though the goofy (but endearing) mascot used by Knedlik was eventually developed by Norsworthy-Mercer, an external ad agency.

Taylor’s designs were modified and finalized by a staff artist at Mitchell Company (the machine manufacturer), and the ICEE company formulated a business plan. For a rental fee, businesses could license a specified number of ICEE dispensers and have exclusive distribution rights in their territories.

By the mid-1960s, 300 companies had ICEE machines in operation; 7-Eleven was one of them.

Birth of the Slurpee

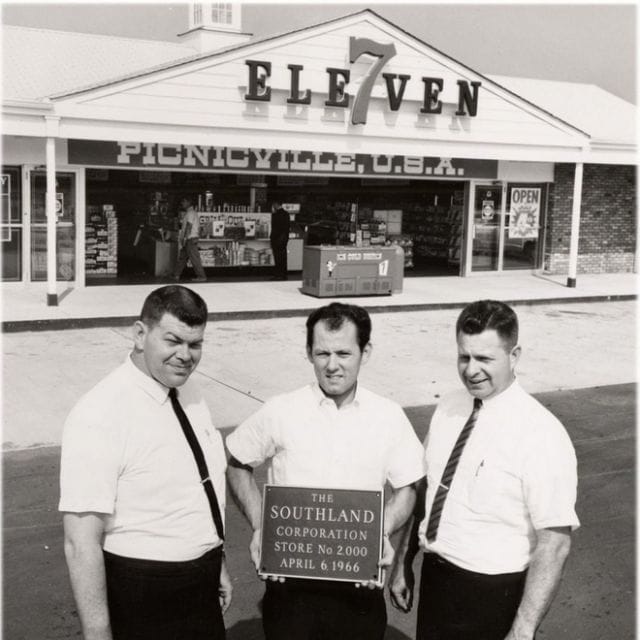

7-Eleven christening store #2,000 in 1968; 7-Eleven

The 7-Eleven franchise started in 1928, when an ice manufacturing employee started selling milk, eggs, and other perishables in front of his Dallas factory. The employee’s manager, Joe C. Thompson Jr., noticed his employee was using the company’s ice to preserve the goods, and saw potential in the idea.

He bought out the ice plant, opened several storefronts, and operated them under the moniker “Tot’Em Stores;” in the early days, each store would be adorned with an original, ornately-carved totem pole imported from Alaska. During the Great Depression, however, “Tot’Em Stores” went bankrupt.

But in 1946, the company rebounded, offering unprecedented operating hours — 7 am to 11 pm. Rebranded as “7-Eleven,” the franchise grew to 100 locations by the early 1950s. After a University of Texas football game one night in 1962, an Austin 7-Eleven saw so much foot traffic that the store was forced to remain open into the wee hours of the morning; the store subsequently experimented with a 24-hour operation on weekends, and soon most franchises followed suit.

As 7-Eleven became more successful, it sought to introduce more “original” products. In 1965, they began a licensing deal with The ICEE Company under two conditions: 7-Eleven must use a different name for their product, and they were only allowed to sell it at 7-Eleven locations.

Inspired by the drink’s ability to induce an oral symphony, Bob Stanford, 7-Eleven’s agency director at the time, re-named it the “Slurpee.”

How Slurpees Became Super Cool

Evolution of the Slurpee cup; Slurpee

Nurtured by 7-Eleven’s savvy marketing team, the Slurpee implanted itself as a cultural phenomenon. According to John Ryckevic, 7-Eleven’s one-time category manager for Slurpee and fountain beverages, the company targeted a young, hip market:

“Slurpee is a perennially young drink. It appeals to kids, teens and young adults and everyone else who remembers the fun of drinking a Slurpee. It is probably the most recognized 7-Eleven brand, and it has a culture and personality all its own.”

In the late 60s, 7-Eleven achieved this by designing psychedelic-looking cups adorned with colorful twists and twirls. They barraged radio stations with advertisements featuring upbeat, funky music; the ads were so popular that people would call in to request them, resulting in free airplay. They became mainstream hits.

One such spot, “Dance the Slurp,” was released as a 45 RPM promotional disc and given out for free in 7-Eleven locations. It was incredibly well-received, and attracted a cult following; today, rare copies of the disc sell for upwards of $50 a copy on eBay, and the song has even been remixed by the likes of Cut Chemist and DJ Shadow.

The Slurpee’s flavors also stirred up attention, with risqué names like “Fulla Bulla,” “Kiss Me, You Fool,” and “For Adults Only.”

“Dance the Slurp” (1970)

By the early 1970s, the Slurpee’s marketers began to realize that cups were prized ad space. Throughout the decade, they were festooned with sponsored artwork — sports teams, comic book characters, rock bands, video games — and became highly-valued collectibles.

Throughout the 1990s and 2000s, special edition cups and flavors would be created to promote blockbuster movies. In 2002, for instance, a blackberry-flavored drink was released in tandem with a limited-edition Men in Black II cup. The same strategy was replicated for Iron Man, The Simpsons Movie, and others; each time, Slurpee cups have become venerated collector’s items, selling for 3-5x the original price.

Marvel Slurpee cups, circa 1977-1979; Source: Cheryl DeWolfe

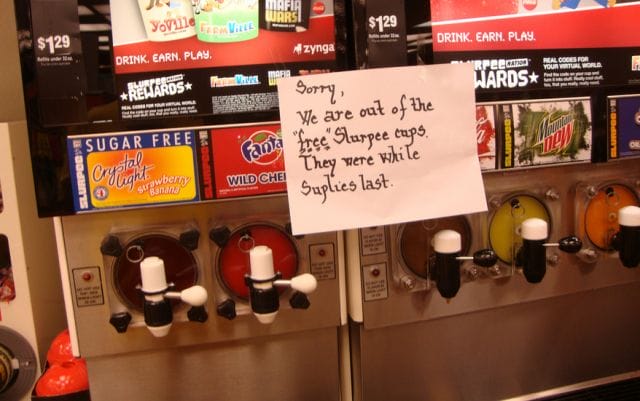

Starting in 2002, 7-Eleven designated July 11th“Free Slurpee Day.” In most stores world-wide, the first 1,000 people through the door of each location are rewarded with a free 7.11-ounce Slurpee; as a result, the company claims to give away about 7 million Slurpees each year.

But don’t get too excited: Barry Schwartz, a professor of psychology at Swarthmore, reminds us why we should be wary:

“Economists are wrong about almost everything. But they’re right about one thing: There is no free lunch — or in this case, free Slurpee…If a [company] offers something for free, people will gladly spend money to get it.”

With Slurpees, this is indubiously the case. For most people, the gasoline required to drive to the nearest 7-Eleven is likely more than the $1 retail value of the “free” good they’re getting. Moreover, if money is time, the 15 to 20 minute average wait time standing in line for a free drink is probably worth more than a buck.

Nancy Smith, 7-Eleven’s VP of marketing, says on Free Slurpee Day, Slurpee sales generally skyrocket by 38%. It’s a similar concept to free samples at a food market: consumers get a small taste for free, then decide they’ve got to have more.

“Slurpee drinkers are some of the most loyal fans we have,” Smith adds. “They come here to have fun.”

The Modern Day Slurpee

Source: Keri

Since the Slurpee debuted in 1967, over 7 billion have been sold worldwide — one for every person on the planet. Ranging in price from $1.15 to $3, the beverage is cheap, bountiful, and widely consumed in more than a dozen countries, led by Canada.

Despite being one of the coldest cities in the Northern Hemisphere, Winnipeg, Manitoba (Canada) has been crowned “Slurpee Capital of the World” fourteen years running. During an average month in the city, 188,833 Slurpees are sold (compared to 179,700 per month elsewhere in Canada). Last year, the city narrowly edged out Calgary and Detroit, and was bestowed the first-ever “Slurpee Capital Trophy Cup” for its effort.

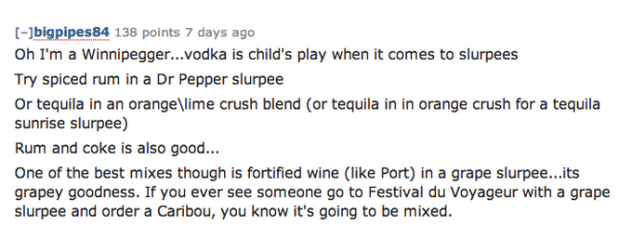

Apparently, Winnipeggers are also Slurpee mixologists; one Redditor had this to say about his approach:

The company has also continued in its long lineage of marketing prowess.

When the U.S. economy was tanking in 2010, President Obama joked that Republicans were “sipping Slurpees” while the Democrats were fighting to rescue the country. When a reporter subsequently asked Obama if he’d be hosting a “Slurpee Summit,” he commended the idea and added that Slurpees were “delicious.”

7-Eleven seized the free publicity by creating a “Bi-Partisan Purple for the People” flavor (blue and red combined), and embarked on a 3,000-mile “Slurpee Unity Tour,” which culminated in a real-life Washington, DC Slurpee Summit. The voyage was a smash hit for the Slurpee: 2,000 media stories were generated, Jon Stewart sipped on a Slurpee on The Daily Show, and Obama’s meetings with Republican officials were inextricably linked to the multi-colored beverage for two weeks.

In the wake of this publicity, 7-Eleven launched “Bring Your Own Cup Day” in Australia and Canada, to great fanfare. For a mere $2.60, Slurpee prospectors can bring and fill any container (provided it fit through an in-store cardboard cut-out); last year, there were reports of people leaving with up to five liters of slush. During Canada’s Slurpee promotion last week, some took things to another level:

Wow #winnipeg? Who was this? #slurpee capital of the world. pic.twitter.com/MfVneC4gY0

— PegOut.com (@pegoutdotcom) March 21, 2014

Slurpee’s Australia marketing division operates what is probably one of the strangest social media pages of any brand, routinely responding with ridiculous answers to customers’ questions, and touting promotions like the “Xpandinator” (a plastic funnel you attach to your cup that enables you to fill it with more Slurpee):

Other over-the-top Slurpee technology also includes a “dual-chambered cup” with a double straw and switchable valves (purpose: two separate flavors, and still have the option to drink them together).

The flavors over the years — all 145 (here’s a comprehensive list) — have been equally zany: “Banana Split,” “Grapermelon,” “Liquid Artillery,” and “Shrekalicious” round out an intriguing (and sometimes terrifying) roster of former options. The creation of a new flavor requires the marriage of science, marketing, and market awareness. Those tasked with the job must stay up-to-date on flavor trends, endure multiple rounds of product testing, and monitor the consistency of the drink when cooled to 28 degrees (the standard for Slurpees). It’s a process that takes months.

Slurpeenomics

Each month, 13 million Slurpees are consumed around the world. At an average price of about $2 (USD) per drink, 7-Eleven makes around $300-350 million in Slurpee revenue each year. Not bad, considering the hypothetical cost of making one.

Andrew Boydston, an ex-convenience store manager, says Slurpees carry an attractive gross margin:

“As store manager, I read the labels coming off the delivery truck, and was able to see what was contributing to the store’s gross product margin. Those Slurpees came in at an astounding .18 cent cost factor, selling for a 1.99 per cup — that’s what made the store money. (By contrast), those lousy Vienna sausages in a tin were sold for $1.99 and made the store only an 18% profit margin, or 36 cents on a $2 purchase.”

As a company, 7-Eleven has historically done very well. In 1971, they reported their first $1 billion sales year; only eight years later, they had their first $1 billion sales quarter; in 2002, they saw $10 billion in annual revenue. Over the last decade, the company has exploded in growth: they went from 20,000 stores in 2003 to over 50,000 in 2013; today, a new 7-Eleven opens nearly every two hours, and revenues are estimated at $77 billion.

The Slurpee may be just a blip on the company’s financial radar, but it seems to be a highly profitable one.

And what ever became of Omar Knedlik, the beverage’s founding father? He received royalty payments from 7-Eleven for 17 years, until his machine’s patent expired in the early 1980s. A slew of other machines entered the market and he faded into the annals of folklore.

But today, his “genius” refuses to be forgotten — even if it was accidental.

This post was written by Zachary Crockett. Follow him on Twitter here, or Google Plus here.