Marc Roth glances nervously around the room. A who’s-who of San Francisco’s entrepreneurs, developers, and community builders have gathered to support his most recent endeavor: a project designed to provide homeless people with free housing, food, and tech classes for 90 days.

Just two years earlier, he was standing in a line with 60 other people, waiting for a meal. He was homeless, alone, uncertain; his two young children and their mother were 562 miles away in Las Vegas.

Despite agonizing setbacks, Roth went from being a statistic in San Francisco’s homeless population to owning his own business. His story of failure, success, and dogged determination tells us what it means to be resilient; his way of giving back serves as a unique model for community-based social reform.

How a C# Programmer Became Homeless

Source: Greg Adams (Flickr)

For the better part of 32 years, Marc Roth called Las Vegas home. A self-taught programmer, he spent much of his early professional life bouncing around between odd jobs:

“I did not have a normal job for most of my 16 years in technology and I feel that’s why it was so hard for me to get interviews later on. Anyone with a brain reading my resume would have to know that I’d eventually quit and go start another business.”

He devoted years to “hacking out Access Database driven software for very small companies,” and familiarized himself with Visual Basic, Microsoft’s event-driven programming language. This led to developing passenger embarkation software and guest onboard status tracking for Crystal Cruises, and programming an interactive taxicab system in C#. He even started his own firm, Roth Technologies, while pursuing a computer science degree from UNLV. Then, in 2009, his company failed.

Struggling to support his family, he floundered to find work. He intermittently wrote software for a point of sale system used in gentlemen’s clubs, but “as a father and compassionate human being,” he was less than thrilled supporting that industry. Enticed by the Bay Area’s high volume of Craigslist listings for sales engineers, he made the difficult decision to move to San Francisco and seek out greener pastures.

![]()

San Francisco wasn’t the utopia Roth had imagined. He knew he’d be living in his car for at least a few weeks after arriving, but the 2008 Saturn VUE ended up being his home for three months. Broke, jobless, and displaced, he maintained a positive outlook:

“I had a strange experience living in my car. It was actually quite hospitable. I slept 90+% of the time near Mission Bay park where they are building the UCSF campus. I spent most of my time at the Mission Bay library using the free WiFi until I had to sell my MacBook. Then I spent my hour a day in there using their computers.”

To support himself while continuing to look for work, Roth got a part-time job at Oasis Café on Treasure Island for minimum wage. A few weeks in, he developed nerve damage from standing all day and not only had to quit, but faced towering medical bills.

On a frigid night in December 2011, Roth checked into St. Vincent de Paul homeless shelter in downtown San Francisco. He lied down in a dark room with with seventy other one-night walk-ins, and stared at the ceiling, waiting for daylight to illuminate its cracks. With the rising sun, he applied for San Francisco General Assistance, which gave him $200 in food stamps, a small monthly cash stipend, and 30 nights of housing in a shelter. For six months, this was Marc Roth’s life.

From Homeless Shelter to Startup Founder

Laser cutter; Source: Barnshaws (Flickr)

Roth’s daily routine was mechanical: 7AM wake-up call, 7:45AM breakfast, out the door at 8AM to find work, back by 5:30PM to stand in line for dinner (anything from a peanut butter and jelly sandwich, to leftovers from a high-end banquet that had been donated to the SF Food Bank). Following this, there’d be an assortment of optional classes — Alcoholics Anonymous, Yoga, Dental Hygiene — before lights-out at 10PM.

But one night, the routine was broken. Roth was lying in bed drifting into an early sleep, when he overheard two men talking on the other side of the loft:

“One was telling the other about a place he found in SOMA [South of Market Street, an SF neighborhood] and took a tour of. He described TechShop and thought the second guy was going to love this idea, and he gave him the flyer. The second guy threw it in the trash. They went into the kitchen to eat or watch TV and I got off my mat went to the trash and took it out.”

TechShop, founded in 2006 by a community college robotics teacher, is a “a member-based workshop that lets people of all skill levels come in and use industrial tools and equipment to build their own projects.” They offer a variety of classes — 3D printing, welding, CNC routing — through which members can learn and develop skills. A major player in the “Maker movement,” TechShop is credited for boosting Silicon Valley’s “hardware renaissance” — a shift toward hand-crafted, physical products.

The crinkled flier — “Come and Build Your Dreams” in bold font — changed Marc Roth’s life. The following day, he took his $59 monthly stipend, bought a banana at Safeway, and took the rest out in cash. He arrived at 926 Howard Street — TechShop’s San Francisco location — an hour before they opened for the morning, paid $49 for a one-month membership, and enrolled in the two free classes that were included as part of a Christmas special.

Roth devoted himself entirely to the community, “studying 12 hours a day,” only returning to the shelter by 7PM to secure a bed for the night. “I helped in every way I could, every time I could,” he recalls. TechShop was rife with brilliant minds creating brilliant products; Oru Kayak (foldable, origami-style kayak), OpenROV (underwater robot), and J-Storm Urban Maps (3-D routed map art) were all up-and-coming companies that extensively used laser cutting, and Roth began offering his services.

He established himself as a TechShop regular, and built relationships with dozens of other startups who’d had successful Kickstarter campaigns and needed laser cutting services for small-scale production. Soon, he was charging $20 an hour — more than twice what he had made working in the café a few months earlier. More importantly, he was on a path toward doing something he loved. As a programmer, Roth had always been taken by the sheer joy of making things; at TechShop, he explored this in a physical arena rather than a digital space. While he was still homeless, he didn’t seem to let it defeat him:

“Broke or not, homeless or not, I was passionately enjoying the living shit out of everything I was doing at the time.”

Roth sent nearly every penny of his earnings back to his family in Las Vegas but it was still barely enough for them to scrape by. Armed with the wandering mind of a serial entrepreneur, Roth soon began to entertain several ideas to supplement his income.

His first idea was to revisit an idea for a pizza startup, which had failed for health code reasons and never got off the ground:

“I had an investor interested in my idea of creating this app-based food disruption model. I was in the middle of MVPing it [minimal viable product, or market testing], when I ran into legal roadblocks. I didn’t have the stability to risk getting into legal trouble with the Department of Public Health.”

Roth ended up pivoting the company into an “honor fridge,” where people would pay what they thought was fair for his delivery service. It made him an extra $75-125 per month, but was still a far cry from what he needed in order to relocate his family.

Then, Roth told the same investor about his idea to launch his own laser cutting business; he was urged to pursue it.

TechShop’s laser cutting machine — a Trotec Speedy 300 — handled most of Roth’s needs, but some of his work demanded the use of a larger one; he convinced a friendly investor to help him purchase his own laser cutting machine, which retailed for $18,000. Roth bought it wholesale overseas, imported it himself, and painstakingly learned to use the Chinese Software. Right around the same time, Roth was extended an invaluable offer: Chris Fornof, a fellow TechShop member and employee at LeapMotion (a 3D gesture control company), offered him a bed at a house for startup founders — and fronted his rent for two months.

Given an opportunity to break the cycle he was in, Roth excelled. He launched his startup, San Francisco Laser and, in a few months’ time, began to turn a profit. Today, he charges $75 an hour for his service — anything from cutting repetitive patterns for scaled production, to etching company logos. He works with a multitude of clients, most of which are recently funded Kickstarter projects, and teaches seven classes at TechShop. Clients rave about his dedication and work ethic:

With a little help, a lot of hard work, and an indefatigable spirit, Marc Roth went from being homeless to owning his own company. Though his business is not incredibly lucrative — he moonlights as a Lyft driver when he needs extra cash — he has made enough to rent his own apartment, move his family to San Francisco, and afford his own workspace.

But he wasn’t satisfied: he had a bigger fish to fry (using lasers, of course). One question kept him up at night: if he could make a transition like this, could others do the same? For Roth, the idea of helping others in the shelters “just didn’t go away.”

The Learning Shelter

While working in the TechShop, Roth teamed up with a friend from his homeless shelter and created CozyLap, an “iPad/MacBook holder for your lap.” The product, which had a rubber-embossed bottom and fuzzy wool top, launched on Kickstarter with little forethought. “It failed so embarrassingly bad,” admits Roth:

While the product flopped, the idea behind it didn’t: Roth’s intention was to get a company off the ground and hire a staff entirely sourced from homeless shelters. He wanted to do more than launch a company; his vision was to create a movement.

Homeless employment programs are bountiful in San Francisco. Project Homeless Connect, created in 2004 by San Francisco’s Department of Public Health, aims to provide the city’s 7,000-10,000 homeless with the necessary resources and skills to find stable work; there are hundreds of similar programs in place throughout the United States. But Roth’s idea went beyond this: he wanted to scale his personal experience, and give the homeless a full start-to-finish course to find work. To do this, he needed a space.

Walking to TechShop one day, Roth noticed there was an empty lot at 1131 Mission Street and had a vision: what if he were to somehow gain access to it and plunk down some shipping containers to house tools for open use in the homeless community?

He researched how he could achieve this, and it led him to Freespace and a man named Mike Zuckerman, a self-proclaimed “culture hacker.” A few months prior, Zuckerman had fought to acquire a month-long lease on the 14,000 square foot building next to the lot for $1, with the help of the Mayor’s Office for Economic and Workforce Development. He turned it into Freespace, a movement dedicated to creating spaces for open community use. Roth shared his ideas about the lot, and Zuckerman took action.

1131 Mission Street lot being repurposed; Source: Freespace.io

He sourced seven shipping containers from other San Francisco nonprofits — ReAllocate, and Ekovillages, both of which experiment with shipping container repurposing — and planted them in the lot adjacent to Freespace. Marc

called these his “Crates of Discovery.” With Zuckerman on board, Roth began laying the groundwork for The Learning Shelter, his ultimate vision:

“We acquired 3 3D printers (via 3D Systems, and Clinton Global Initiative), built a curriculum for the first 30 days, derived 75% of our current board of directors, built a couple websites, made a logo, reached out to sample candidates, talked to 2,000 people about the idea, and have forged relationships with communities all over San Francisco.”

So what exactly is The Learning Shelter, how will it impact San Francisco’s homeless community, and what are its future implications?

![]()

The Learning Shelter’s initial vision is simple: select four candidates from San Francisco’s homeless shelters and give them 90 days of free housing, food, and tech classes. By the end of the program, each participant would ideally leave having mastered one employable skill (CNC routing, laser engraving, welding, etc).

To be selected, a candidate must be a current resident at a homeless shelter and on good terms. Qualified candidates will be set up with face-to-face interviews, and their skill sets will be tested. Roth says most programs similar to his are either first come first served, or lottery-based; his will be based on the desire to succeed, and a show of determination.

Once selected, the program’s participants will follow the general outline of the program:

Day 1: Participants come into the living space, meet the team, and find out what’s on the horizon for the next 30 days. We watch some TED talks, eat dinner, and relax.

Day 2: We arrive at TechShop and get acquainted with our space. We take our first class in 3D modeling, and learn the basics of 3D printing. Assess roadblocks to personal success.

Days 3-30: Explore different classes (ie. vinyl cutting, silk screening, Adobe Illustrator for CNC, laser cutting, basic wood shop and metal shop).

Days 30-90: Participants begin determining what they’re most interested in, and choose a specific course to follow. They take on a mentorship at TechShop, and master a craft, with the goal of having them stay on after day 90 in some capacity (new hire, trainee).

Though The Learning Shelter plans to operate out of the TechShop, they have secured their own space there in the “Annex,” and have the majority of their own tools — computers, 3D printers, silk screening rig — save for a laser.

![]()

The Learning Shelter’s Indiegogo Video

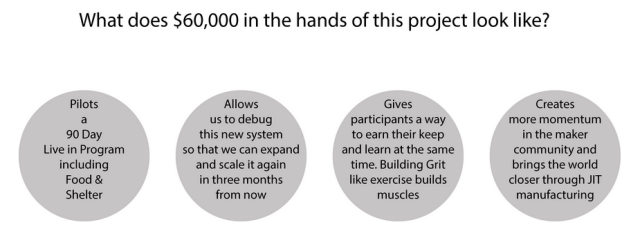

On February 3rd, Marc Roth launched an indiegogo campaign to fund The Learning Shelter, with a goal of raising $60,000. This money would cover an apartment for each candidate (at market rate), three meals per day, and market rate corporate memberships at TechShop. It will also cover 80 classes (20 per candidate), which usually run about $50-70 each. Roth says, “If we had exactly $60K didn’t get any breaks on cost, we would finish with $0 in the bank.”

Currently, Roth’s campaign is at $5,513 (9% of his $60,000 goal), with 12 days remaining.

Roth hopes that he can cut the expenses for each candidate (finding subsidized housing, for example), but also says he doesn’t want handouts from TechShop, or housing agencies:

“We will negotiate professionally and seek good deals, but The Learning Shelter is meant to be a valuable part of the community and to teach participants how to take ownership of their commitments and deliver above expectations — not receive handouts.”

While the participants will be getting free education and housing, they’ll also be producing about $15,000 worth of goods each, says Roth. Under Good Samaritan Law, whatever the participants produce won’t be considered taxable income, since it’s part of an education.

Crawling Toward the Future

Any money left over from the campaign, says Roth, will go toward future iterations of The Learning Shelter. Roth’s future plans are well-mapped: he intends to scale the program’s next iteration to 30 participants; he foresees a vast living space with showers and beds, and plans to put the 8×20 foot shipping containers to use as privately-operated learning centers (a la TechShop). For all of this, Roth estimates about a $500,000 budget.

Five years from now, Roth envisions his project being open-sourced, with a global support system that can help anyone with a budget and a desire to change the social climate of homelessness.

“I would love to see it spawn a bunch of for-profit entities and allow the VC community to come in and help us prove to the world that it doesn’t matter where you start, and as long as you have desire and tenacity, getting to your goals is just a matter of making it happen.”

But like Roth’s personal journey, The Learning Center will require patience and small, measured steps. “We’ll be running someday,” he vows, “but we need to crawl before we even start walking.”

This post was written by Zachary Crockett. Follow him on Twitter here, or Google Plus here.