![]()

In the first episode of season four of Breaking Bad, Gus, the boss of a large drug operation, enters an underground meth lab, where his cooks, Walt and Jesse, are quietly seated. Slowly, Gus descends — clank, clank, clank — his shoes tapping against the metal stairs. Without speaking, he walks to a dressing area, meticulously removes his suit jacket, ring, and eyeglasses, and zips into a biohazard suit. The room is dead silent.

During the three-minute scene, there is little dialogue, and a minutia of sounds can be heard: squeaking chairs, footsteps, the swooshing of pant legs, and slow, steady footsteps. Then, with little warning, Gus raises a box cutter, slits the throat of one of his trusted workers, and holds the man’s head as it spurts loud, gushy streams of blood across the room.

As the scene’s plot thickens, and as the dialogue picks back up, its easy to forget about the atmosphere of tiny sounds you’ve been exposed to. After all, they were so natural sounding, that they seemed to be picked up on the set — at least that’s what Gregg Barbanell, the man who created them, wants you to think.

Barbanell is a Hollywood “Foley” artist, a member of a small, highly-skilled group of experts who add custom sounds into television and film scenes in post-production, using a bevy of makeshift props. Named after one of film’s earliest sound pioneers, Foley is an antiquated craft — and in a digitized era of cinema, it is one of the last of the industry’s “low-tech” jobs.

These folks are responsible for recording nearly every footstep and prop sound in the movies — the things that you never really notice, yet bring a scene to life. It’s at once one of the most important elements in film, and the most overlooked. Unlike sound effects editors, Foley artists don’t rely on libraries of pre-recorded sounds: they perform them “live,” using creativity, intuition, and a small dose of physics.

In his 35 years in the trade, Barbanell has over 500 credits, including huge hits like Breaking Bad, The Walking Dead and Little Miss Sunshine — though you’ve probably never recognized his work: the best Foley blends so seamlessly with the scene, that it is lost to the viewer.

So, what’s it like to be Hollywood Foley artist?

The Road to Hollywood

Gregg Barbanell (left) and his son, holding a few of the MPSE Golden Reels he was awarded for his Foley work

Born and raised in the San Francisco Bay Area, Gregg Barbanell had a “storybook childhood,” one full of creative support, wonderment, and exposure to the arts. After starring as John Proctor in his high school’s production of The Crucible, he knew, with certainty, that he wanted to be an actor.

He applied to only one college — the prestigious and highly competitive California Institute of the Arts — and was accepted into its theatre program. But by the end of his first year there, he began to question his career choice.

“For a lot of our exercises, they’d break us into groups of six students — and one of the actors in my group happened to be Ed Harris [who went on to be a four-time Academy Award nominee],” says Barbanell. “He was phenomenal. I mean, oh my God, he was so good. At some point, one of my professors told me, ‘Honestly Greg, you’d make an okay television actor, but that’s it.”

Around this time, Barbanell was asked to write a script for a friend; he enjoyed the process so much that he decided to apply for a transfer into CalArts’ film school. Famed filmmaker Alexander Mackendrick, who was the school’s dean at the time, was impressed by Barbanell’s script and took the young student in as a mentee.

At the time, the program was quite exploratory. “This was the 1970s, and everyone was experimenting with film. All kinds of crazy stuff was going on,” says Barbanell. “I had one teacher say, ‘We’re screening a movie next week, I’d advise you to show up in an alternate state of reality.’ I mean, it was wild.”

In the summer after his final year at CalArts, Barbanell joined a few independant filmmaker friends, “put together a caravan,” and went off into the remote stretches of Idaho, Utah, and Colorado to shoot a Western film on no budget. Other than some sparse dialogue, the movie was silent, and in desperate need of sound editing. With very little knowledge of what he was doing, Barbanell offered to take over:

“By the seat of my pants, I borrowed some sound libraries, and cut all the sound — everything — to an entire feature film that had no sound to begin with. When we took it to get mixed at MGM Studios, the mixers said, ‘Who the hell cut this stuff?!’”

MGM was so excited by Barbanell’s sound editing, that they offered him a job; instead, the recent grad decided to start his own company. “I had a choice to work for the studio, or be my own boss,” he says. “I said the hell with it — I can do this — and I decided to do the latter.”

In 1979, Barbanell launched his own post-production sound company, Mag City, Inc., and embarked on a career supervising sound for films. Over the next seven years, it became a rather fruitful business — but Barbanell realized he wasn’t fulfilled creatively, and sold the company to his friend, Dane Davis (who’d later go on to win an Academy Award for Best Sound Editing for The Matrix).

“Right after I sold the company, I started getting calls from all my ex-sound editor competitors, asking me to do ‘Foley’ work,” says Barbanell, “and since then, I’ve never stopped.”

The Hidden World of Foley

Foley, or the physical creation of custom sound effects for films, is employed in nearly every major blockbuster today — though its roots extend back nearly a century.

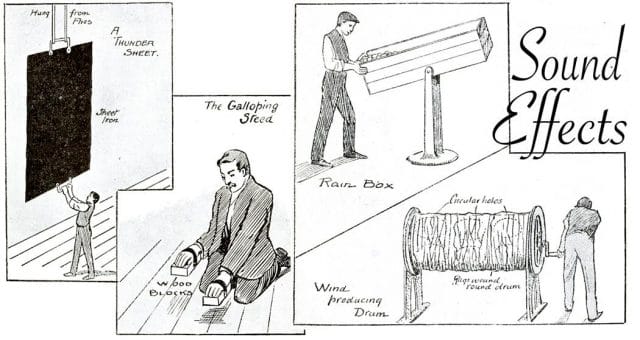

Radio producers in the 1920s often enlisted any object they could find to replicate the sounds of the elements in their stories. To imitate the hooves of galloping horses, they’d bang coconut halves on the floor; to emulate a baseball bat hitting a ball, they’d snap wooden matchsticks in half; for thunder, they’d shake thin metal sheets. These sounds, writes historian Jack French, were “simple, unsophisticated, and often not very convincing” — but realism was neither expected from viewers, nor prioritized by showmakers.

When Warner Studios released The Jazz Singer, Hollywood’s first feature-length movie with sound, in 1927, the film world was thrust into a new era of “talkies.” Jack Donovan Foley, a man who’d previously produced silent films for Universal, was tasked with adding sounds to an upcoming musical picture — things like footsteps, creaking doors, and gunshots. At the time, even the best microphones solely picked up dialogue: in order to integrate sound effects, Foley recorded them “live” after the film was shot, on a single track of audio.

Often inaccurate and fake-sounding, these early attempts didn’t appease critics of sound films. “Unless new sound effects are soon discovered and judiciously employed,” wrote French filmmaker René Clair in 1929, “it is to be feared that the champions of the sound film may be heading for a disappointment.” Despite this, the “Foley” method gradually evolved over the years, and became a mainstay in cinema all over the world.

***

In 1986, fresh out of Mag City, Inc., Gregg Barbanell entered the Foley scene as a freelancer. At the time, Hollywood was experiencing what he calls a “Foley renaissance:” only 8-10 teams teams of Foley artists made a living full-time, and they all knew each other. “During Christmas time, we would all call each other and say, ‘We should raise our rates this year!’” he recalls. “It was like a big family.”

Today, the industry has become so competitive that Foley artists undercut each other to get jobs. Barbanell estimates that there are somewhere between 50 and 70 full-time Foley artists in Hollywood today — only half of whom make “a decent living.” As a member of Warner Brothers’ sound team, he’s among the fortunate.

Gregg Barbanell at his ‘second home:’ Warner Brothers’ foley stage

Barbanell’s job — to create custom, post-production effects for movies — can be broken down into three components: “cloth, feet, and props.”

Typically, “cloth” comes first, and is also the most subtle of all Foley effects. “Cloth is the track that records the movement of everyone’s clothing — they use it to fill holes,” clarifies Barbanell. “If there’s a scene where the dialogue has been replaced, and the background noise has been stripped out, making subtle clothing noises makes it sound more real.” To emulate the sounds of subtle actions like an actor crossing his legs, Barbanell rubs pieces of specifically-selected fabric together.

Next up, and probably the most important aspect of Foley, is the “feet” — or recording, one by one, every character’s footstep in the entire film. Though it sounds simple enough, Barbanell says this is the most challenging aspect of Foley:

“Being able to do the feet extremely well with all the nuances and shifts — that separates the boys from the men. It’s not something you can learn. It’s just a feel thing. The feet are where you’re judged as a Foley artist.”

“Imagine a character,” he adds. “He’s on cement; now he’s inside on a wood floor; now he’s going up a fire escape; now he’s not wearing tennis shoes anymore, he’s wearing a boot!

It’s a tedious process — and especially challenging for actors like Jackie Chan, who moves so quickly — but we do every footstep for every character on every surface.”

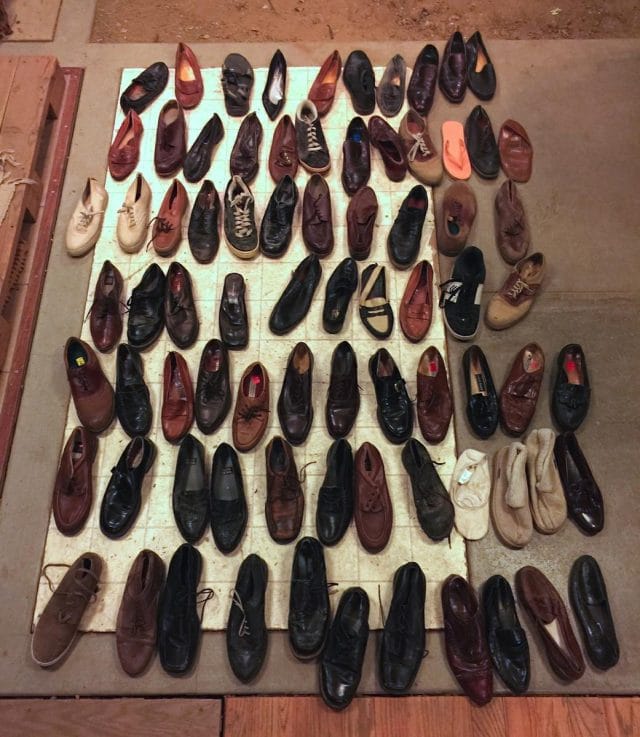

To achieve this, Barbanell has amassed a collection of over 100 pairs of shoes (though only 15 to 20 are in his “regular rotation”):

A small sampling of Barbanell’s shoe collection — all used strictly for sound, of course

“I’m constantly at Goodwill, thrift shops, and flea markets, on the search for a great sounding pair of tennis shoes or women’s shoes,” he says. “I’ve got five big moving boxes filled with cleats, flip flops, ballet slippers, tap shoes — you name it.”

Over the years, sound editors have attempted to digitize this aspect of Foley with keyboard samples — but according to Barbanell, “the human element can’t be automated:”

“To get the minutia — the tiny shift, the slide, the difference in rate from the heel to the toe — isn’t possible with technology. With the feet, it’s a performance thing. You have to read the actor. If someone is shy and hesitant, that translates to how you do the footsteps. If someone is evil, that translates. You have to get the feel of what’s going on in the scene.”

When all of a film’s footsteps are recorded, Barbanell moves onto the most expansive and creative sector of a Foley artist’s job: “prop” sounds.

A Man of Many Props

Gregg Barbanell’s garage would qualify him for the television show Hoarders. Dozens of plastic boxes line the walls, each packed to the brim with chunks of metal, old tools, telephones, hats, and knick-knacks of every conceivable variety. But Barbanell isn’t compulsive in his collection of these things — he’s thorough. It’s an integral part of his job.

In addition to recording the footsteps and subtle clothing movements of on-screen actors, a Foley artist must replicate a variety of random sounds in film; to do so, he must maintain a healthy stable of props. But, as Barbanell admits, he’s a bit more more “obsessed with finding the right props” than some other Foley artists out there.

Barbanell’s Southern California garage, stuffed to the brim with props of all sorts

Warner Brothers’ Foley prop room houses its own set of props — everything from metal tools to suitcases

Finding his props is a long, arduous process, but one he takes great pleasure in.

“I go scan swap meets, yard sales, Craigslist,” he says. “I’ll be driving down the street, I’ll see things people are throwing away, and I’ll have to stop and put them in my car. It’s all for the sake of sound.”

Of course, aesthetics play no role in Barbanell’s acquisition process: “it’s all mundane stuff — but I buy it because it sounds amazing:” Anything that makes unusual sounds or squeaks, he clarifies, is especially desirable:

“I pick stuff up, turn it, twist it, see if it screeches, or wiggles. In my job, it doesn’t matter how something looks. Nobody ever sees it. All my props are purely and only purchased because of the way they sound.”

Generally, it’s his responsibility to go out and find his own props — and it’s also his responsibility to pay for them out of pocket. Many Foley artists rely on their studio’s stock prop room, though Barbanell insists on going the extra mile to find the perfect sound for a scene. Recently, in pursuit of a revolver for a time-period film, Barbanell went to six different gun shops until he found one with just the right cylinder spin. “The other Foley artists think I’m nuts,” he says. “It was $600, but I had to have it just for that sound. I don’t buy a gun if it can’t help me with some crazy sound.”

Props used by Barbanell for The Walking Dead

It’s a process, he insists, that requires a “sixth sense” for what will work and what won’t. “I’ll know if I’m in the ballpark, but you don’t really know until you get to the stage,” he says. “You have to manipulate things; having the prop is one thing, but knowing what to do with it is another.” It also requires a general knowledge of the physical properties of things:

“There is some science involved. A lot of it has to do with physics — especially sonics and resonance. Being able to get the right resonance out of something and being able to manipulate it — it’s too woody, it’s too “metal-y” — you can change that. You can know how to do that by having a good sense of the world, but it’s also about learning the physics.”

Once he has what he needs for a scene, Barbanell sets up his wares at Warner Brothers’ Foley studio film, where he receives a print out with hundreds of prop cues, each accompanied by a time-stamp. “We break props down into color codes, so we can be more efficient with time,” he says. “If we were to go chronologically, we’d be there for ever. Time is a Foley artist’s worst enemy.”

Over the years, Barbanell has done “hundreds of thousands” of prop cues for more than 500 films, television shows, and video games. A few in particular stick out in his memory:

The Walking Dead

Popular apocalyptic zombie TV series The Walking Dead has no shortage of gore — and as the show’s Foley artist, Barbanell is tasked with creating most of its gruesome “blood and guts” sounds. “They’re pulling organs out of bodies, they’re slicing heads off, reaching into bodies, pulling out things,” says Barbanell, with disgust. “So, we get creative.”

For “gushy, squishy sounds” like oozing blood, Barbanell uses chamois (a leather cloth made from the skin of mountain sheep). “You soak it, then lay into it, and it just oozes — it’s something you can control really easily,” he says. “And when you put pressure on it, you get these amazing, gory noises.” Sometimes, when that extra oompf is needed, he’ll go out and buy a whole, raw chicken to stuff the chamois inside of.

For “breaking bones,” big, full stalks of celery are employed — not merely individual stalks, mind you, but HUGE bunches capable of producing layered, complex snaps. “They give you this huge, sinewy stringy sound,” adds Barbanell. “It’s very effective.”

For sharper, harder sounds like “crushing skulls,” Barbanell relies on whole walnuts. “I’ll hold two in my hand and crush them, or very gently crunch them with my feet,” he says. “It sounds exactly like the crushing of bones.”

All of these props combined, says Barbanell, are extremely effective in producing an off-putting, gruesome atmosphere.

Little Miss Sunshine

In the 2006 comedy Little Miss Sunshine, a family travels across the country in an ailing VW Microbus with a broken clutch. Barbanell was tasked with finding a sound for the vehicle’s rusty sliding door, but ended up incorporating a whole new schtick into the movie:

“I happened to accidentally find this funky old pickup truck tailgate in a junkyard. When I stepped on it, it made this amazingly funny creaking noise — EEEEERRRHHHHKKK. Instead of using my prop for the sliding door sound effect, I used it when the family had to get out and push the thing to get it going. That sound effect actually got a laugh at screenings.”

“Adding a laugh that wasn’t there before — that’s like the brass ring for Foley artists,” Barbanell says. “Yeah, I was proud of that.”

Bubble Boy

For Bubble Boy, a 2001 comedy about a boy with no immune system who is forced to live in a plastic bubble, Barbanell was tasked with finding a prop to emulate the constant friction of plastic.

“I had this South Park inflatable sofa that I’d bought for my son — this big vinyl thing,” he recalls. “I found that when I inflated it about half way, it gave me the right noise for the sound of the bubble.” Throughout the film, every time the boy (played by Jake Gyllenhaal) moved, Barbanell’s inflatable South Park couch made a guest cameo.

“It was funny as hell,” he says.

Breaking Bad

Though Barbanell has worked on many enjoyable projects, he cites Breaking Bad (2008-2013) as the best experience of his career. He provided Foley work for every last episode of all five seasons of the show — and because he was given up to three and a half days per episode to find props and record sounds (a rarity in his time-starved job), he was able to produce some of his most impressive work.

In the fifth episode of season five, Jesse and Walt, the show’s main characters, rob a train. At one point, Jesse has to climb underneath the locomotive and twist off a huge metal cap, producing an array of metallic noises — chains, hinges, “clinking” sounds. “I went out for a half a day to one of my favorite metal junkyards just buying props for that one scene,” says Barbanell. “I think I spent $200.”

In the tenth episode of season four, Walter and Jesse are annoyed by a lone fly buzzing around in their underground lab. “The whole scene had extreme close ups of this fly doing this fly stuff — rubbing its legs together, fluttering its wings, shaking its body,” says Barbanell. “This is stuff you never, ever hear, but because it was Breaking Bad and I knew it would get played, I worked on just the fly close-ups for 40-45 minutes.”

“The beautiful thing about Breaking Bad was that every episode had that level of attention,” he adds, “and because of that, the passion of the whole cast and crew was brought out:”

“I became tremendously emotionally invested in Breaking Bad. That show meant everything to me. It was sort of like I was set free to let every creative thing in me come out. I wanted to do everything my way, and they let me. And the cool thing was, everyone involved felt that way — from the writing to the sound team, to the people on the set. Everybody realized very quickly how special this was.”

“When it ended, I think I suffered some post-partum depression…I really missed it.”

Big Demands, Big Rewards

Barbanell teaching a Foley master class at Chapman University

After more than 30 years as a Hollywood Foley artist, Gregg Barbanell is at once self-satisfied and exhausted.

“I have to worry about my age; it’s a very physical job,” he says. “I’m out there every single day, getting up at 5:15 in the morning, pounding on stuff, jumping up and down. I’d equate being a Foley artist to cleaning houses all day long, or working for a moving company.” When his doctor asks him how much exercise he gets, his response is candid: “I get plenty.”

Even more tiring than the physical is the mental stress — the concentration and unwavering focus required of Barbanell on a daily basis. “You’re sitting there with every muscle ready to fire, and you’re staring at the screen for every cue — BOOM! POP, POP! BOOM, BOOM, BOOM! POP! You do that for 8 hours, you get pretty fatigued.”

In his occasional visits to film school classrooms, Barbanell doesn’t necessarily extol the virtues of Foley to interested students. “It’s not something I would necessarily recommend,” he admits. “The competition is fierce now, it’s tough to get into, and its certainly not something you’ll get rich doing.”

But for Barbanell, the value of his craft transcends any negative repercussions. “I freaking love my job,” he says. “That’s something I try to instill in my son: Just find something you love to do. If you can get people to pay you for what you love to do, that’s success.”

As he tells us about his son over the phone, Barbanell suddenly reels back to his own youth, and is reminded of “Gerald McBoing Boing,” his favorite book as a child.

“It was about this kid who spoke with sound effects instead of words; his parents were worried sick, and tried everything to cure him,” he says. “But by the end of the book, his ability to make these sounds ended up saving the day, and the world accepted him. You could say that stuck with me.”

![]()

This post was written by Zachary Crockett. You can follow him on Twitter here.

To get occasional notifications when we write blog posts, please sign up for our email list.