Standing straight, with right hands over hearts, millions of children recite the words every year: “I pledge allegiance to the Flag of the United States of America, and to the Republic for which it stands, one Nation under God, indivisible, with liberty and justice for all.”

The Pledge of Allegiance is nationalistic, religious, and patriotic — indicative of the values espoused by our country’s leaders. But there’s another quintessentially American angle to the mantra: it was invented by a marketer who was looking for a creative way to sell flags to public schools.

Monetizing Patriotism

In 1827, a young publisher founded The Youth’s Companion, an American children’s publication that focused on “virtue and piety” and “warned against the ways of transgression.” By the late 1880s, it had become the country’s most circulated weekly magazine, with some 475,000 readers. Some of the greatest voices of the time — Mark Twain, Booker T. Washington, Emily Dickinson, and Jack London — regularly contributed, and the Companion gained a reputation for high quality writing.

But the owner at the time, Daniel Sharp Ford, felt the publication wasn’t realizing its full potential. In 1888, as a premium to solicit subscriptions, he launched a campaign to sell American flags to public schools. At the time, a schoolhouse flag movement sought to “place a flag above every school in the nation.” The Youth’s Companion quickly became its most ardent supporter.

In 1892, Ford’s right-hand marketing man, James B. Upham, was tasked with coining a marketing gimmick that would inspire schools to buy more flags. Upham, in a spurt of genius, decided to monetize patriotism by creating a “pledge” in which children would declare their undying love for America. He hired Francis Bellamy, a Baptist minister, to write something that could easily be recited in “15 seconds or less.”

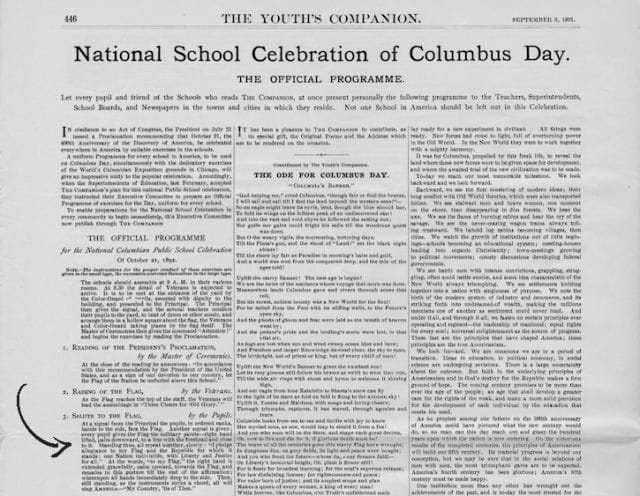

A socialist, Bellamy wanted to include the words “equality” and “fraternity” in the pledge, but his editors rejected the idea on the basis that state superintendents opposed the idea of equality for women and African Americans. Bellamy acquiesced, and on September 9, 1892, the original version of the Pledge of Allegiance made its debut in The Youth’s Companion:

“I pledge allegiance to my Flag and to the Republic for which it stands, one nation, indivisible, with liberty and justice for all”

Original September 8, 1892 copy of The Youth’s Companion, featuring the Pledge of Allegiance

A few weeks earlier, President Benjamin Harrison had called upon the people of the United States to celebrate the first national Columbus Day, in honor of the explorer’s 400th anniversary of “discovering” America. Harrison requested that educators spend the day teaching children the ideals of patriotism (ie. “support of war” and “loyalty to the nation”).

Bellamy subsequently spoke at a national convention for school superintendents, where he sold the idea that his pledge should be instituted as a part of this “official Columbus Day program.” He was ultimately elected chair of the committee, and formulated the entire holiday around an elaborate flag-raising ceremony and his pledge.

The campaign was massively successful. By the end of the year, the magazine had sold American flags to more than 26,000 schools across the nation — at a hefty profit for The Youth’s Companion. The pledge became a fixture in public schools; to this day, it is recited in tens of thousands of classrooms.

Fodder For Controversy

For years, the Pledge of Allegiance was accompanied with the “Bellamy salute,” a gesture invented by The Youth Companion’s marketing man, James B. Upham. In Bellamy’s own recollection, upon reading the pledge for the first time, Upham had snapped his heels together, raised his arm at half-mast, and enthusiastically roared his support: “Now up there is the flag; I come to salute; as I say ‘I pledge allegiance to my flag,’ I stretch out my right hand and keep it raised while I say the stirring words that follow!”

The 1892 article that introduced the pledge included the following instructions on how to integrate the salute:

“At a signal from the Principal the pupils, in ordered ranks, hands to the side, face the Flag. Another signal is given; every pupil gives the flag the military salute — right hand lifted, palm downward, to a line with the forehead and close to it. At the words, “to my Flag,” the right hand is extended gracefully, palm upward, toward the Flag, and remains in this gesture till the end of the affirmation; whereupon all hands immediately drop to the side.”

In the 1920s, however, German Nazis adopted the Roman salute — a gesture that strongly resembled Bellamy’s — as a show of support to Adolf Hitler and his ideology. In 1942, Congress amended the Flag Code, replacing the Bellamy Salute with the hand-over-heart gesture, which is practiced today.

In 1954, another amendment proved controversial: sensing the perceived threat of Communism, President Eisenhower asked Congress to add “under God” to the pledge. The inclusion has been contested dozens of times over the past 60 years — both in federal court and state courts — and has consistently been dismissed.

Today, there are many objections to the recitation of the Pledge of Allegiance. Opponents argue that their First Amendment rights grant them the agency to decide whether or not to participate — or whether or not their children should be forced to participate. Others argue that the pledge goes against the tenets of democracy and diversity. But for those who are wholly aware of the pledge’s origins, there is another reason to reject the pledge: it was born not out of a desire to commemorate our nation, but as a clever ploy to get us to buy a product.

We wrote a book that you’ll probably enjoy → Everything Is Bullshit.

This post was written by Zachary Crockett. Follow him on Twitter here, or Google Plus here.