Online Advertisement for Spirit Halloween Superstore

One of the more obscure bits of Halloween folklore is that the modern Halloween industry was started in 1978, by a magician that Sears Roebuck would hire for public events and office parties. His mother was a San Diego costume-maker. After years of seeing her shop’s business explode every October, the magician told Sears he wanted to open a temporary Halloween shop within the local store.

“Everybody thought it was crazy,” the magician — whose name is Chuck Martinez — told a reporter in 2011. In the 70’s, the idea of a Halloween-centric store was considered, “kind of crazy, or at best, a silly business plan.” But Martinez talked Sears into it, and got his mom to take out a mortgage on the house to help finance the operation.

It paid off. That first location generated “around $89,000 […] during a 35-day selling period.” The operation was a national chain by 1984 with over 360 locations and, “multi-million dollars of retail revenue during the month of October.” 1988, ten years after he started the shop, Martinez sold his business back to Sears for $6 million.

Whether or not Martinez is the industry’s sole “pioneer and founding father”, it’s true that Halloween stores just weren’t around in the early 1970s. Today, they’re virtually everywhere. Many more stores than Sears’s sprang up in the 1980s, and business has been expanding ever since. Now, between candy corn, the gratuitously “sexy” costumes, and the front yard decorations, the sector makes an estimated $8 billion a year — most of that in October.

How did all this happen? As every failed entrepreneur of President’s Day paraphernalia will tell you, you can’t make a holiday dud a holiday hit just by opening a store. Was Halloween always such a cash cow? If so, why did it take retail until the 1970s to figure it out?

A Different Kind of Holiday

A quick internet search, book skim, or cruise through the History Channel yields the following history of Halloween:

The holiday probably has its origins in the Celtic festival of Samhain (sah-win, or sow-in), which marked the end of the harvest and the beginning of winter. Samhain was swallowed by All Saints Day when Christianity came to Ireland. This is where the etymology of Halloween derives — to hallow something is to honor or consecrate it, and a hallow is a saint:

“Halloween — c.1745, Scottish shortening of Allhallow-even “Eve of All Saints, last night of October” (1550s), the last night of the year in the old Celtic calendar, where it was Old Year’s Night, a night for witches. A pagan holiday given a cursory baptism and sent on its way.”

The result of this “cursory baptism” was a muddled mix of Christian and pagan rituals — to celebrate you made offerings to the old gods so they wouldn’t screw with your livestock, did spooky stuff by bonfire to figure out who you were going to marry, and lit church candles for dead relatives.

Halloween didn’t make it to North America until the Irish did, by the hundreds of thousands, in the mid-19th century. For a while it was an ethno-political holiday for Gaelic immigrants — a kind of St. Patrick’s day in the fall, but it assimilated soon enough. Pranksters stopped carving out turnips for their jack-o’-lanterns, finding pumpkins — a New World crop — much easier to work with.

“Guising” was a 19th century Scottish tradition of going from door-to-door in costume, caroling or reciting verses in exchange for gifts — usually sweets or money. This begging for “treats” also came with the danger of “tricks”, as “imitating malignant spirits” was taken as a good excuse for mischief by the likes of the infamous gangs of New York.

Over the next century, that mischief got to be a little much for some. Nicholas Rogers, author of Halloween: From Pagan Ritual to Party Night, pranksters regularly clashed with the police once cities started having police forces (municipal government has come a long way in the past two hundred years). And guising took on a desperate tone in the Depression Era 1930s, as many children and young people literally needed the food they were begging for. The 1934 World’s Fair in Chicago would have ended in some pillaging of the concession no matter the night, but by choosing to close it on Halloween, “the authorities should have predicted trouble”:

“At midnight, some 300,000 revelers, some of them masked as witches, took complete control of 32 miles of streets and concessions, “drank everything in sight except Lake Michigan,” and rifled everything “moveable as souvenirs.” At the horticultural building, for example, “thrifty housewives” were reported taking home $200 plants as admission souvenirs. Hundreds of police reserves were brought in to clear the crowds from the fairground, but crowds were still pouring in as late as 3 A.M.”

In the post-war years, the efforts to tame the rebellious side of Halloween amounted to a national movement. In 1950, the U.S. Senate passed a bill recommending that Halloween be re-branded as “Youth Honor Day”, on which school children would take a pledge against destroying property in exchange for a ticket to a party or dance. According to Rogers, trick-or-treating as we know it — in which “children dressed up and unreflexively requested candies from local neighbors with little sense of what ‘tricking’ might mean” — was also part of this movement. Rogers says it was introduced to North America in 1939, and widespread by the 1950s.

As you might have noticed, very little in this history — from the begging your neighbors for food, to the vandalism of their property, to the holiday’s iconic decoration being a homemade gourd-lamp — screams “big business”. People had always thrown Halloween parties and dances, for their friends or for their church. Trick-or-treating in the post-war years were a little spendier — confectioners and costumers started to make money. This was all pretty small-fry compared to the superstores of today.

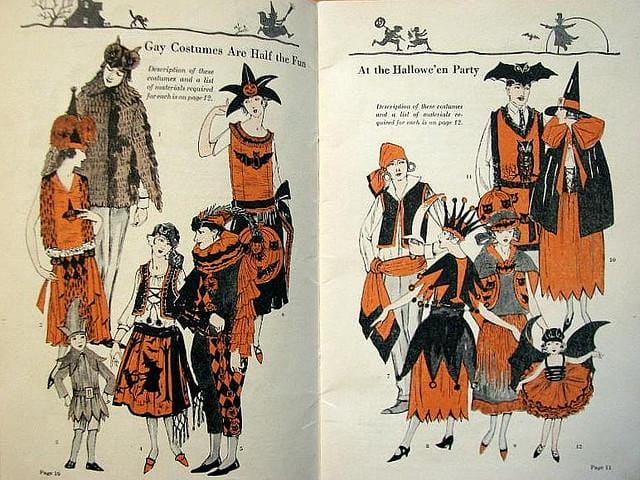

The History Channel has a segment titled “Halloween Goes Commercial”, profiling Halloween superstore Spirit. A historian on the program says that Halloween was definitively commercialized by a paper company releasing a Halloween crafts magazine in 1913.

WOMAN: They sold crepe paper, seals, decorations […] [and] they told you what to do with it. I can’t say enough about what Dennisons did for Halloween because they commercialized it.

CUT TO SHOT OF SPIRIT HALLOWEEN SUPERSTORE

NARRATOR: And Halloween never looked back.

There’s something missing here: if this paper company started the Halloween industry, why did it take another sixty years for department stores to start selling Halloween items like they would Christmas items? Stores like Spirit stock things you never would have seen in a 1913 paper company’s magazine, which raises the question: where did today’s Halloween consumers come from? Like the kind of people who buy and then squeeze into costumes like this:

The Halloween industry boomed in the 1980s, and for that to happen, something must have happened: after the crepe paper, before the “slutty” children’s television show character costumes. Something that didn’t fit into the official TV-history of a family-friendly holiday.

A Real Drag

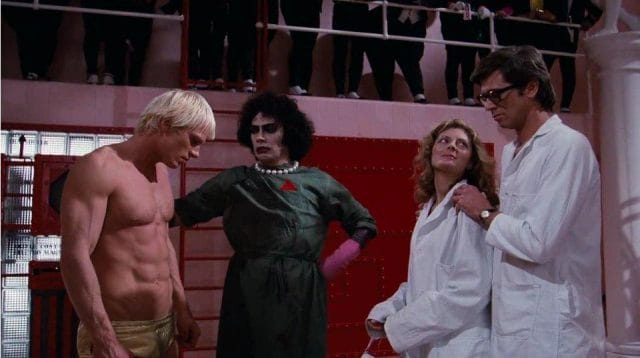

Still from The Rocky Horror Picture Show

In the 1970s, adults started celebrating Halloween like never before — as an extravagant carnival, akin to Mardis Gras. Parades! Floats! Booze! Music! Glitter! Disposable fashion! This happened when Halloween, which first took foothold in America as a celebration of Irishness, became the flagship holiday for a different minority group — another group that also, definitely knew how to party:

[In 1971] in New York City, a Broadway drag rock show from San Francisco, starring the Cockettes—”a spangled chaos of flesh, a seething mass of hock-shop costumes, doing their thing for freedom”— staged an impromptu Halloween parade on East 9th Street.

Queer culture had adopted Halloween.

The LGBT Liberation movement was one of many currents of social upheaval that happened between 1913 and 1980. The Stonewall Riots of 1969 brought the movement into the spotlight. These were communities of outsiders, who often adopted personas — some of them costumed — for interacting with the “straight” world. Halloween was a rare public opportunity to actually play with the presentation of your sexuality, without having to fear “outing” yourself. Rogers found a quote Montreal Gazette: “Hallowe’en is the one evening of the year when Jacques can masquerade as Jacqueline and Jacqueline as Jacques.” That sentence was printed in 1931.

One might see a pre-cursor to the “slutty Halloween” phenomenon in this quote — an analog to the “Mean Girls” narrator’s assertion that, “Halloween is the one night a year when a girl can dress like a total slut and no other girls can say anything about it.” Jacques can masquerade as Jacqueline, and a heterosexual prude can “masquerade” as somebody who actually enjoys sex. (There are many complicated gender politics at play here, but this “gratuitously sexy costumes are like drag for women” dynamic is definitely part of it.)

Philadelphia threw large drag parades from the 1940s through the 1960s when “homophobic violence had reached such proportions” that the police shut them down. According to Rogers, parades sprang up “wherever the gay community felt confident enough to celebrate their sexuality and affirm their right to public space.” In New York, the Cockettes’ 1971 drag parade gave rise to more, including one thrown in 1974 by a Greenwich Village puppeteer.

Village Halloween Parade: Phoenix, 2001

These parties were spectacular, and straight people started attending — lots of them: the puppeteer’s parade became the Village Halloween Parade, which is now the largest Halloween parade in the world. But even the early Philadelphia parades drew a friendly and curious audience, before they drew a violent one: “[I] didn’t see anything but good nature, unless they were tourists who were just there with their mouths open to their shoes and not saying anything, just in total disbelief,” one reveler recalled.

Though transvestism never quite went mainstream, sexy clothes in general did. “When somebody says, ‘I want to drag for the first time!’” Zsa Zsa Glamour, a San Francisco drag queen and community organizer told us, “I ask them what kind of ‘look’ they want, and they say, “’Oh, I want to look like a slut!’ Same thing with girls. They’ll say, ‘I want to look like a tramp for once in my life!’”

“Gay communities planted the seed, then retailers did the rest of the work,” reads a Slate article titled “When Did Sexy Halloween Costumes Become a Thing? The 1970s”. The radical inclusiveness of these parties was also good for retail: with street parties, everyone’s invited! And if everyone’s invited, then everyone needs a costume — and starting in the 1980s, they were probably buying some of those costumes at Sears. From an essay by author Lesley Bannatyne:

[…] just when it was looking like Halloween would fall out of favor for all but the very young in their parents’ company, celebrations by adults, often spearheaded by the gay community, came to define Halloween in certain cities in the U.S. In San Francisco’s Castro district, Provincetown, and Los Angeles, impromptu costumed Halloween gatherings of the late 60s and early 70s grew larger and larger. More and more, adults were searching for Halloween entertainment giving rise to the huge celebrations […] By the 1990s, the haunted entertainment industry had exploded.

As Bannatyne says, topsy-turvy atmosphere and the extravagant style of celebration also caught on. Squelched in the McCarthy Era, the holiday’s mischievous spirit was back, bigger than ever. And this time, instead of burning down the status quo, the elements society had deemed “malignant spirits” had banded together to form a large and elaborate new world order, with a place for the deviants. Rogers quotes a Washington Post reporter in 1983 who describes that world as looking something like this:

‘[…] in the belly of the blast, it was like an Easter parade of freaks … to say nothing of the flashers who offered outrageous peaks. As Washington staked its claim as San Francisco East, glitter and gloss were everywhere and the roar of the grease-paint and the swell of the crowd engulfed Georgetown, magically transpoofing it into an androgynous and anthropomorphic street fair. Men dressed as women; women dressed as men; . . . men and women dressed as things that could heal the sick, raise the dead and make little girls talk out of their heads. Acting out their most sublimated fantasies, strutting their stuff, whirring and purring like figurines on an elaborate cuckoo clock. As Butch said to Sundance, “Who are those guys?”’

This new incarnation of Halloween was fun, sexy and deviant. It was the whole world transformed into Dr. Frank N. Furter’s spooky transexual “Transylvanian” castle. Over on the other side of the country, San Francisco — Washington of the West, hotbed of the freaks — was just getting started.

Abridged Indulgence

Group shot from left to right. Cardinal Sin, Sister Zsa Zsa Glamour, Sister Juanita La Bufadora (now deceased), Sister Olive O’Sudden, front Novice Sister Kitty Catalyst.

“The first Halloween parties were impromptu,” Sister Zsa Zsa Glamour reminisced. In 1989, she and her charity troup of drag nuns “the Sisters of Perpetual Indulgence”, were responsible for the first of a series of official Castro Halloween celebrations. By then the San Francisco gay community had been celebrating Halloween their way for decades.

Zsa Zsa moved from Detroit to Santa Cruz in October 1981. She was sort of a country mouse when it came to the city’s queer scene: “I didn’t know anything back then — I didn’t know there was a gay neighborhood, I didn’t know what the bars were like.” On the advice of friends, she bought a ticket to a San Francisco Halloween party. It was there, stepping out of the party onto Polk Street for a minute, that she first saw a drag queen stop traffic.

“They would throw toilet paper rolls over the Muni wires to stop the buses,” she remembered. “And then drag queens would stop traffic just by carrying on in the middle of the street, giving their performance. Next thing you knew you’d have a street closure, just by accident!”

On Halloween of 1989, the Sisters lead an impromptu fundraiser, “with a ladder and a bullhorn” for Loma Prieta Earthquake relief. They collected thousands of dollars. This inspired them to organize the first official Castro Halloween the following year.

“Sister Vish used his connections in City Hall to get the permits and things to do a legitimate street closure,” Zsa Zsa said. “He contacted the gay men’s chorus because that was one of the largest organized groups of gay men. We put on a stage show and we just made it up as we went along. We didn’t know what was going to happen.” Like Zsa Zsa, Vish is still with the Sisters. Back in 1990 “Vish” was an abbreviation for “Vicious, Power-Hungry Bitch.” Now he’s “Vish-Knew.”

Zsa Zsa’s act that year was to dress as Dianne Feinstein, and do stand-up. A lot had happened since Zsa Zsa’s first San Francisco Halloween in 1981. For one, when she arrived in California, the gay scene was in the process of mass migration from Polk Street to the Castro — thus the migration of Halloween street festivities. For another, 1981 was the year the CDC first recognized AIDS.

Some of the Sisters of Perpetual Indulgence’s earliest work was in promoting awareness about AIDS and raising money for AIDS research through street performance. By 1990, the epidemic had decimated the community both in body and in spirit. By taking charge of Halloween, the Sisters — a group of mostly gay men dressed as nuns, wearing intentionally gaudy, clown-like makeup — were attempting to restore the community in more ways than one.

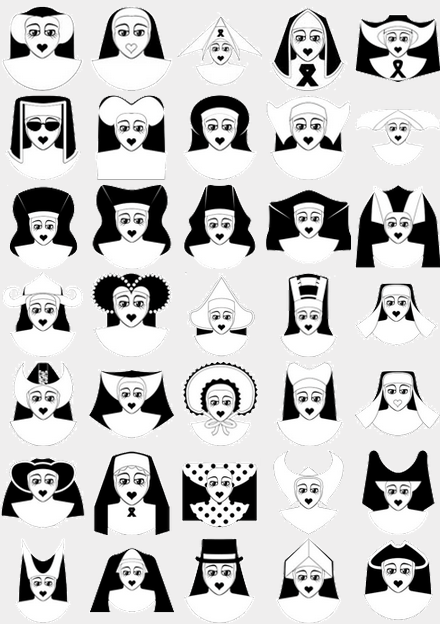

“The lightness of everything, in addition to the whiteface and the nun’s habits,” a member of an Oregon-based chapter of the Sisters told a reporter, “are a mechanism to reach out to people. When we’re dressed up like that, kind of like sacred clowns, it allows people to interact with us.” The Sisters now have a presence in several states and countries. The different orders are distinguished by the shape of their wimples:

Wimples of the world, Sisters of Perpetual Indulgence

The first official Castro Halloween in 1990, the Sisters collected money for AIDS charities. The unofficial Castro Halloween was already an attraction, but once the Sisters got involved it was a smash hit. In 1994 — the last year the Sisters would organize — between 300,000 and 400,000 people attended.

“We had a stage at the north end of Castro and Market. It was a spectacular show with 30 acts and costume contests. For the big finale we shot off fire works in between two gas stations and all those Muni lines,” Zsa Zsa laughed.

“But it had gotten too big for us to manage, especially without city support,” she said. “It started to get out of the gay community. Plus you would get people whose bright idea for an axe murderer or a Texas chainsaw massacre costume was, ‘I’ll just bring a real axe or a real chainsaw.’”

Street celebrations continued without the nuns until a shooter wounded nine people in 2006. The city deployed a massive police force — 600 strong — in 2007 to prevent the event from “happening spontaneously.” This also happened the year after that. Cops directed revelers to events in other parts of the city.

The public campaign was called Home for Halloween program, and was in essence a San Franciscan pledge of honor to either celebrate at home or at least confined to a quiet neighborhood. “No crowds for me this year!” the slogan read.

The Sisters have forged on, too, separate from their flagship holiday. They’ve started managing events at different times of the year, instead. Pink Saturday is part of Pride Week — which is the current, overtly political flagship holiday of the queer community. On Easter, the Sisters also run the “Hunky Jesus” competition in Dolores Park, for long haired, bearded individuals who look good shirtless. Zsa Zsa mentions that a little monetary or more organizational support from the city would definitely be welcome.

Sisters of Perpetual Indulgence, photo shoot for HallowQueen 1995

“We’re nuns, we’re humble,” Zsa Zsa said. “We don’t profit — it’s all either charity or it goes back into our operating cost.”

There’s an irony here, although it might sadly be a familiar one. While what Slate wrote might have been true for the sexy costume business — that “the gays planted the seed, and the retailers did the work” — in terms of the Halloween ecosystem the retailers were also making the bulk of the money, and the gays were putting in a lot of work. Now, it seems, consumption is rolling on — the National Retail Federation expects another 7+ billion Halloween this year — but the revelrous spirit of the holiday has been reined-in.

This year Zsa Zsa is going to a private party she goes to every year. The costume theme is “Cher Wolf,” but she said she thinks she might just fall back on her fallback. “As a sister — you always know what your costume is,” she said. Woman of the cloth, priestess to the less-lucrative side of fun. Soldier on, Sister. Soldier on.

This post was written by Rosie Cima; you can follow her on Twitter here. To get occasional notifications when we write blog posts, please sign up for our email list