Everyone arrives late to parties. This is not universally true, but it is close enough that it is common practice to invite people to arrive to a party at 8pm that you actually intend to start at 9pm.

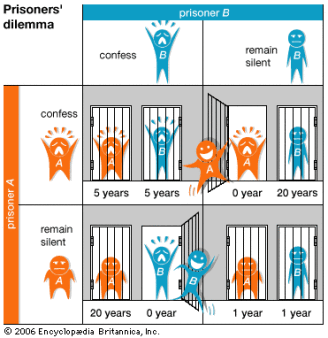

This norm of tardiness can be ascribed to culture, as partygoers are much more punctual in Germany than in, say, Brazil. But we think game theory – the same framework behind the prisoner’s dilemma – does a much better job explaining why people persistently arrive late. Partygoers arrive late because they face a dilemma in which arriving late tends to maximize their enjoyment of the party.

An illustration of the dilemma faced by two prisoners who committed a crime together. If they remain silent while being interrogated, the case against them will be weaker, resulting in a short sentence. A prisoner could reduce his sentence by ratting out his fellow prisoner, but if they both confess, then they will both receive longer sentences. Since the prisoners cannot be sure of what the other will do, the rational choice is to confess.

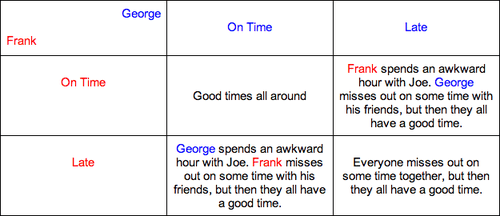

Here is an example. For simplicity, let’s imagine a three person party hosted by Joe. Joe invites his two friends, Frank and George, to his house. The three are good friends, but they haven’t seen very much of each other lately and would like to spend as much time as possible together at the “party.” Joe is not the most entertaining host, however, so the party won’t be very fun until all three of them get to Joe’s house.

This is what happens based on whether George and Frank each arrive on time:

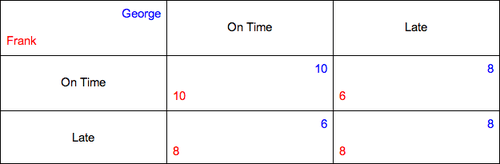

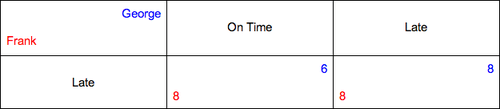

Here are the same results described with numbers representing their enjoyment of the party from 6 (least enjoyment) to 10 (most enjoyment):

The best outcome is for Frank and George to both arrive on time so that everyone spends the most possible time together enjoying the party. However, both Frank and George want to avoid the awkwardness of arriving before the other friend arrives. Given that they can’t predict what the other will do, here is what their options look like for deciding whether to arrive late or on time:

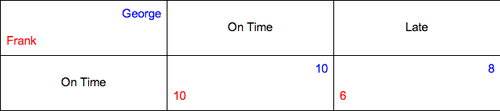

George’s options if Frank is on time. If Frank is on time, George should arrive on time as well to maximize his enjoyment of the party.

George’s options if Frank is late. If Frank is late, then George should arrive late as well.

As we can see, there is no single right decision for George to make. Depending on what Frank does, the utility maximizing decision could be coming on time or arriving late. Frank faces the same dilemma.

So what happens? Absent any wildcards – like Frank having a history of always showing up late – our money is on both George and Frank showing up on time. Since the party only consists of 3 close friends, the level of trust and accountability between the friends is high. Arriving late would feel disrespectful to the other friends.

At a large house party, however, we would expect the exact opposite. Since the level of trust and accountability is lower among a bigger group, the partygoers will have less faith in everyone else arriving on time and feel less guilty about being late. Humans have a bias toward risk aversion, so people will tend toward arriving late to avoid the awkwardness of being the lone, on-time arrival.

Being “fashionably late” to a party isn’t about appearing popular. It’s a utility-maximizing decision predicted by game theory.

This post was written by Alex Mayyasi. Follow him on Twitter here or Google Plus.