As 2013 drew to a close, commentators summed up the year by pointing to our obsession with hit TV shows like Breaking Bad, the National Security Agency surveillance debate incited by Edward Snowden, and the popularity of twerking. But 2013 was also the year that feel good viral videos and images clogged Americans’ Newsfeeds on Facebook. Why are your friends always sharing the same damn video as if they were the first ones to discover it?

In other words, one of the most notable development in the 2013 media landscape was the rise of viral farms — websites that garner huge amounts of traffic, mostly from Facebook, by republishing shareable content that was originally produced elsewhere. They follow a clear formula:

1) Find cool Youtube link or image

2) Slap on catchy title

3) Hope it gets shared on Facebook so you get lots of traffic to your site.

This formula has allowed publishers to generate staggering amounts of traffic (that equate to impressions to sell advertisers) from Facebook simply by scraping content from other sites or Youtube. The result? Viral farms all host the same content with the hopes that their page is the one that gets shared on Facebook.

Take the feel good holiday video put together by the Canadian airline WestJet. In the video, the airline figures out what Christmas gifts the passengers on one of its flights wants, and when the plane lands, has the gifts waiting for them.

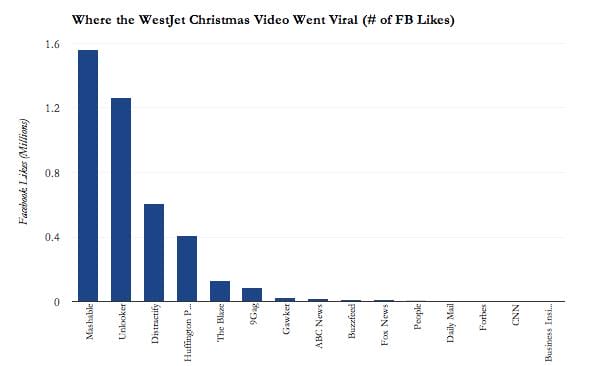

If you’re even an occasional user of Facebook, you probably saw the video shared in your Newsfeed. But which website did you actually see it on? Probably Mashable, where it got over 1.5 million Facebook shares. Here’s a list of websites featuring the video and the number of Facebook shares it received through various publishers in the “viral farming” game:

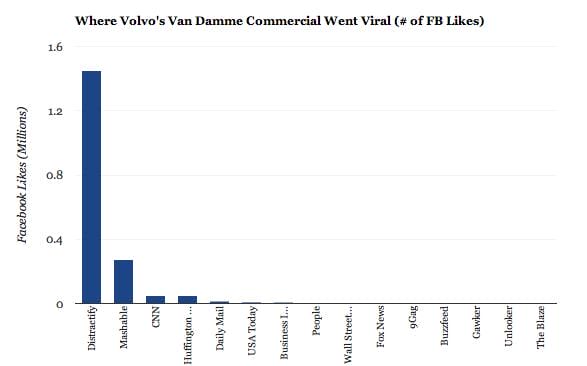

Jean Claude Van Damme’s advertisement for Volvo trucks went equally viral on Facebook. But you may have seen it seen it on a different site, Distractify, where it dominated the Facebook sharing game with almost 1.5 million shares on Facebook.

You get the idea. But how does this happen? Why are all these sites fighting tooth and nail over repurposing the same content? Why do some win and others lose at going viral and what value do they add exactly?

Context & Cumulative Advantage

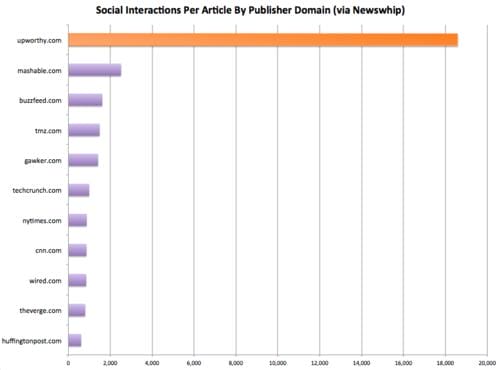

The first thing that these websites provide is context that primes the visitor to consider the content interesting. All of these viral videos are sitting on Youtube, often gathering dust. It seems to requires an interesting headline and short write up to make something go viral. Consider the case of Upworthy, which finds older videos that their audience might find interesting, optimizes the headlines by testing 25 different versions, and then unleashes the most popular one with great effect. The site only posted 246 times in the month of October, but each one got an average of 18,000+ social shares. That’s almost 8 times more shares than the nearest viral competitor, Mashable.

Source: Upworthy

Another key to viral farms’ success is “cumulative advantage.” Cumulative advantage (or preferential attachment) refers to a process where the outcome is determined by the existing wealth of the participants. In this case, “the rich get richer” in the sense that the winning viral farm that pulls in the most traffic from a piece of viral content is heavily determined by the size of the publisher’s existing audience (# of Facebook fans, email subscribers, direct traffic it can promote content to).

This explains why large websites that produce their own original content (like the Washington Post, Time, and Mashable) have an incentive to get in the viral farming game. They already have a sufficiently large audience to make things go viral. Why not post viral pictures and videos when it’s basically free traffic?

Our blog post “Diamonds are Bullshit” is an example of cumulative advantage. On our site, it received 94K Facebook likes. With our permission, the blog post was reposted on Business Insider and The Huffington Post, two sites with a larger audience than Priceonomics. On Business Insider the post received 228K Facebook likes and 770K visits, just by coasting off their existing audience. On The Huffington Post, the post received 80K Facebook likes and probably quite a high amount of traffic without any actual effort. Good work if you can get it!

Facebook can drive enormous amounts of traffic to a site. If you have an existing audience, your marginal cost of republishing a viral hit is zero and the potential traffic upside is enormous. Even if you don’t have a large audience, if you’re savvy at providing the right context, you can get lots of traffic from Facebook. Distractify got 21 million visitors it first month by borrowing the most effective tactics from Upworthy (titles that provide a “curiosity gap”) and Buzzfeed (cater to an audience that’s bored at work). 21 million visitors in the first month of launch is almost too good to be true!

Facebook, and to a lesser extent Twitter, reward those that are skilled at the viral farming game with a deluge of traffic. One writer at Gawker (who recently left the company) accounted for approximately 30 million page views per month in this way, more than all the other writers combined. A picture of The Pope with a clever headline on the Washington Post website brought in a million visitors in a day. Who needs Woodward and Bernstein when you have Facebook and YouTube?

Parallels to SEO and Content Farms

We’re now arriving at the point where Facebook is likely to address the issue of viral farms, just as Google has dealt with content farms. It’s reported that Facebook’s founder Mark Zuckerberg has a distaste for this kind of content, even if his users delight on clicking on it.

As little as 5 years ago, it was pretty easy to get massive amounts of traffic from Google. Put some content on your site that people are likely to search on Google and then let people find you by Googling things. If you were a site that ranked well (had a cumulative advantage), there was an extra incentive to create content just for Google or scrape duplicate content from other sites so you had a lot of pages indexed by Google.

Michael Arrington at TechCrunch documents the phenomenon in 2007:

Blogs and mainstream media sites are indexed by Google very frequently. Many times per day, in fact. And those sites often have great Page Rank already. Combine that regular indexing and Page Rank with Google’s recent policy of ranking news type results higher than older, evergreen stuff, and you have a system ripe for abuse.

Let’s say I run a popular political or celebrity gossip site (two topics that pop up a lot on Google Trends). I look for hot queries that people are typing in right now, for whatever reason. Then I write a blog post, making sure to use the query term in the title of the post (which weights heavier for matching content to specific queries). The content of the article itself is mostly irrelevant, as long as your normal readers don’t gag on it.

Within a few minutes that content is indexed by Google, and the high Page Rank of the site along with the newness of the content pushes it up towards to top of the first page of results. Possibly all the way to the top.

Google eventually caught on to this. It penalized scrapers or those with thin content and only rewarded original content. Google also reportedly made it much harder for young upstarts to gain a foothold in Google’s results. Chris Dixon comments, in a post titled “SEO is no longer a viable marketing strategy for startups“:

I talk to lots of startups and almost none that I know of post-2008 have gained significant traction through SEO (the rare exceptions tend to be focused on content areas that were previously un-monetizable).

It’s very likely that you’ll see Facebook emulate Google’s lead and crack down on duplicate content and tilt its ranking algorithm towards “trusted brands” (aka ones with an rich cumulative advantage). For whatever reason, for now, that means that Buzzfeed is enjoying Newsfeed algorithm adjustments in its favor, resulting ins 130 million monthly visitors to the site. That could change on Mark Zuckerberg’s whim (witness the demise of Zynga, Viddy, and the whole first and second generation of the Facebook platform).

Conclusion

Viral image this author’s wife finds particularly funny. Original source: who knows.

We’ve likely hit a point where a computer algorithm could be the most successful site on Facebook, and that means the viral farming party is about to end. One could simply write an algorithm that detected most shared pages on a handful of websites (say Buzzfeed, ViralNova, Huffington Post, Distractify, 9GAG, etc) and then Copy Exactly! those pages. Eventually multiple people will realize this and bots will rule the Facebook Newsfeed just like they once did the Google Search Results pages.

And then Facebook will change the rules and the viral farm phenomenon will come to an end. We might have an instinct to share viral videos and funny pictures with our friends, but that doesn’t mean that it’s in Facebook’s best interest to let us.

This post was written by Rohin Dhar. Follow him on Twitter or Google Plus. Thanks to Ammar Mian for research. To get occasional notifications when we write blog posts, sign up for our email list.