On the fifth day of Star Wars, Chewbacca said to me:

“GRONNK GRONK-GRONK GRONNNK!”

— The Twelve Days of Star Wars (Tom Smith)

![]()

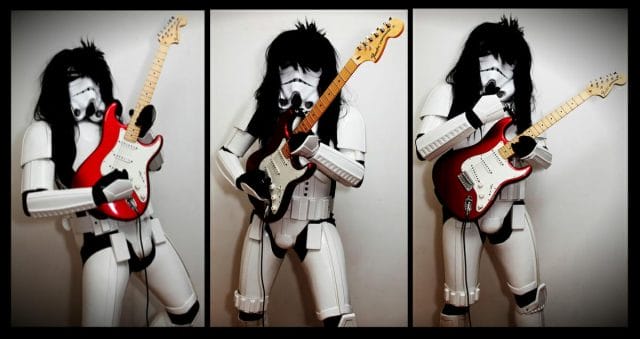

Substitute lines of cocaine for lines of H.G. Wells, trade in crowds of adoring groupies for a group of intrepid Dr. Who fans, swap fog machines and strobes for a foldable chair and a $50 acoustic guitar: you’ve got “filk” music. Though more likely to have Chewbacca figurines thrown on stage than undergarments, filk musicians are the unrequited rockstars of the science fiction world.

For those on the outside, the sci-fi culture is intensely strange, mysterious, and endearingly nerdy — con attendees are, in general, typecast as “Trekkies” or Issac Asimov fanboys. Au contraire, there is a vast, oscillating sea of small communities that operate within the “con-verse;” at its oft-unexposed center, are the filkers.

To modest fanfare, they compose epic parodies that weave together complex sci-fi themes. They sing of elves, pirates, spaceships, and cats, and are “utter nerds” from humble backgrounds, who’ve found a supportive, nurturing community.

In order to contextualize the very niche culture that is filk, let’s take a step back and talk about the genre’s mothership: the science fiction convention.

Sci-Fi Fandom and the Origins of Filk

Celebrities at the first Worldcon in 1939: Howard Stark, Forest J. Ackerman, and Howard Hughes (wearing a rocket-propelled one man flying suit prototype); Source: Rob Jan

Apple engineers, brain surgeons, musicology Ph.Ds, paleontologists, rocket scientists: you never know who you’ll find at a sci-fi convention. Prim and proper in professional settings, they come to cons as Spocks, Klingons, and Madame Vastras, completely disregarding — if only for a night — the fact that they are members of the human race. The origins of this fanbase extend from the same breed of fanaticism.

In 1936, six science fiction readers from New York City took a train to Philadelphia to converse with a few fellow enthusiasts in Philadelphia. Upon meeting, they rejoiced in their mutual nerdiness, and unofficially declared the event the world’s first “science fiction convention.” The following year, the meetup was replicated in Long Island, New York — this time drawing a crowd of 40.

By 1939, enough science fiction fans had emerged to collectively establish the first “World Science Fiction Convention” (Worldcon). Launched in conjunction with the 1939 World Fair, the event drew 200 people, and stayed fairly constant in popularity until fading out completely during World War II.

When the convention re-surfaced post-war, a new sub-community came with it. Harry Warner Jr., a “fandom” and filk music historian, recalls the instrumentation that rose out of the 1947 WorldCon’s chaos:

“The 1947 Worldcon was perhaps the first of the big drunken worldcon parties. Fans gaped in disbelief at John Campbell sitting on the floor, helping Hubert Rogers and Benson Dooling [well-known sci-fi authors and artists] to sing a variety of bawdy ditties.”

By the 1952 WorldCon, small groups of attendees were joining together in hotel rooms with acoustic guitars and performing impromptu science-fiction themed jams, featuring gems like “Glory, How We Hate Ray Bradbury.” Linda Melnick, a musician who was a part of this early scene reflects on how filking formed as an ad-hoc community interest:

“We were a small group, playing in hallways and hotel rooms until neighbors knocked and told us to shut up (which happened a lot). The convention’s [organizers] started noticing that more people at cons were staying up into wee hours of morning to play with us, and decided to integrate it more.”

Around this time, in the early 1950s, the word “filk” was also conceived, accidentally. A die-hard fan wrote an essay on the trend, titled “The Influence of Science Fiction on Modern Filk Music;” his misspelling of “folk” widely spread, and would inadvertently go on to become the defining term for the new genre.

Over next next twenty years, filking was slowly established as an “acknowledged activity” at science fiction conventions. Organizers allotted specific spaces at the cons for filkers to perform, invited guests of honor, and encouraged the community to grow. In 1979, FilkCon was established as an entirely separate convention solely for filk enthusiasts, and was followed by a slew of others; today, there are 10 dedicated “filk cons.”

The Ohio Valley Filk Fest (OVFF), the largest of these events, began giving out the Pegasus Award in 1984 — described by one filker as “the Grammy of filk music.” In 1995, a Filk Hall of Fame was established; it has since etched 60 filkers into the odd annals of filklore.

What the F is Filk?

Scene from documentary “Trekkies” (1997)

The patrons of filk music have struggled to define their own genre.

According to Bill Sutton, a long-time filk artist, categorizing the music is “like trying to nail down an ameoba, or pick up jelly off the floor and carry it across the room.” Another filk artist chimes in, “Ha! You may as well ask me to describe the merits of Vulcan T’Pol’s rear end in Star Trek’s Harbinger Enterprise! [insert other inaccessible sci-fi references here].”

But the generally accepted definition, as delineated by filker Gary McGath, holds that “Filk music is a musical movement among fans of science fiction and fantasy fandom, emphasizing content which is related to the genre or its fans.”

In other words, it’s science-fiction related lyrics (original or parodied) set to traditional folk music. Even more broadly, says another filker, “it’s the music of science fiction fans — and we don’t just like science fiction stuff!”

Filker Margaret Middleton adds that filk songs cover a wide range of subject matter — space, life as a sci-fi fan, technology, engineering, wizards, elves, and “a bunch of other fuzzy stuff.” “An awful lot of science fiction readers also own cats,” she adds. “So yeah, there are an awful lot of filk songs about cats.”

Jordin Kare, a retired rocket scientist and filker, lays out the general outline for filk: the music is stylistically folk (acoustic guitars, mandolins, vocal accompaniment); the lyrics are generally based in a shared fantasy world (ie. Star Trek, Dr. Who, popular sci-fi books); and, of course, the singing is “extremely bad” (the traditional filkish key is “off”).

Even certain songs from major artists can be considered filk: Elton John’s “Rocket Man” (based on a Ray Bradbury story), and Peter Schilling’s “Major Tom” (which riffs on David Bowie’s “Space Oddity”) both qualify.

Weird Al Yankovic, a Grammy-winning parody artist, is often brought up in the discussion of filk, but apparently wants nothing to do with the community, citing its “amatuer nature” (the filk community doesn’t necessarily hold his tunes in high regard either: one filker describes Weird Al’s song “The Saga Begins” as “basically a straight retelling of Episode One, with one lame joke.”)

Pride of Chanur (Leslie Fish)

Within the sci-fi con community, filkers are a vast minority and a tight-knit bunch. Often skirting under the main attractions, they largely keep to themselves but maintain an all-inclusive, encouraging atmosphere for those who may be interested in joining in. “If you have aspirations of singing or writing something,” Kare tells us, “the filk culture is very accepting. Anybody is welcome to perform in a circle.”

A filk circle, or “Bardic circle,” is one of two ways musicians congregate and share music at a con; performers sit in a circle and take turns singing songs, often “riffing” off one another. The other method, particularly used with larger groups, is “chaos:” singers jump in whenever they want (this often brings out “the dreaded ‘filk hogs,’ who insist on singing every other song.”)

Xeni Jardin, a blogger and occasional filk observer, describes the typical interaction seen in a filk gathering:

“It’s like a hootenanny on another planet. Audience members sometimes cheer topically — a song featuring bioengineered chickens is met with clucking. Another featuring pigs in space, with oinks. Another about the physics of farting is met with — well, you get the idea.”

But who are filkers, where do they come from, and what’s it like to be one?

The High Times of Filkstars

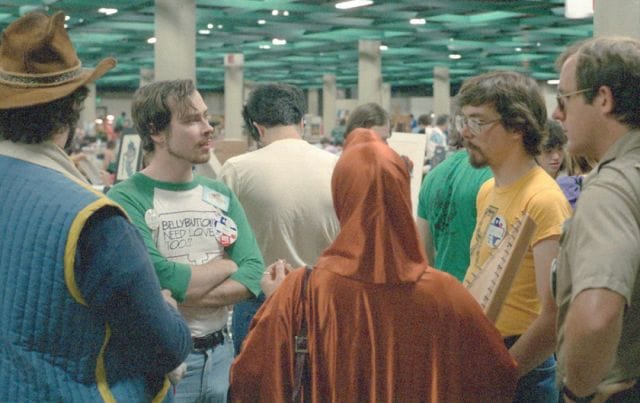

Filkers at LoneStarCon, 1985; Source: Michael Kube-McDowell

For many years, Jordin Kare was a “freelance rocket scientist” and astrophysicist; today, he’s “merely” an inventor (with 250+ patents to his name) and the co-founder of LaserMotive, a company which uses laser beams to transmit wireless electricity. Among his accolades, he was a NASA-funded researcher, a physicist at Lawrence Livermore National Institute, and a pioneer in laser propulsion technology.

He’s also a filker.

While pursuing an electrical engineering degree from MIT in the mid-70s, Kare was “literally dragged into filking” by an eager friend who recognized his interest in science fiction, as well as his affinity for music. For Kare, it was “love at first verse;” soon, he was performing original songs, inspired by his work and interest in space.

His “HEL Crew’s Song,” for instance, is based on a 1972 academic paper on laser propulsion; “Bloody Bastards” is a ballad decrying the companies attempting to privately monetize space travel (though he had to change the companies’ names, as they were investors in his business endeavors); “You Can Build a Mainframe From the Things You Find at Home” is an inspirational ode to those who construct their own computers (originally written by Bill Sutton).

I’ve had my system running, I’ll admit its not the best.

The data isn’t right, and the response time is a mess.

It crashes every hour and isn’t worth a damn,

But I’m satisfied because it runs just like an IBM.

— Verse from “Do It Yourself” (Bill Sutton, 1985)

More recently, following the loss of space shuttle Columbia in 2003, a copy of Kare’s song Fire in the Sky was passed onto astronaut, Buzz Aldrin. Aldrin was so taken by the lyrics, that he chose to read a selection of them out loud during a nationally televised press conference — something that Kare is “immensely proud of:”

Though a nation watched her falling, yet a world could only cry

As they passed from us to glory, riding fire in the sky

— Verse from “Fire in the Sky” (Jordin Kare)

![]()

Gary Hanak is an engineer for a “very large national defense contractor” in Missouri. He has a BA in electronics, and an MA in computer science. Like Kare, his early exposure to filk was accidental — though Hanak recalls being a musician before being a science fiction fan.

“I started playing the accordion at 5. I don’t know if you’re aware of the history of the accordion, but it does not qualify as a babe magnet. So, somewhere around high school, I started playing guitar. Oddly enough, that didn’t work too well either, but I had less things thrown at me and they had less sharp edges, so that was progress.”

Hanak fell in love with science fiction after reading Robert Heinlein’s “Have Space Suit, Will Travel” at age nine, and by the 1980s, was a regular attendee at sci-fi cons. At one event, he recalls, he “happened to see a woman walking through a convention carrying a guitar;” he followed, struck up a conversation, and haphazardly found himself immersed in a filk circle.

“Nobody could really play an instrument,” he recalls, “so that helped me. I hadn’t a clue what filk was, but I could follow along and play.” Hanak immediately drew a parallel to 60s hippie culture, in which “sitting around in circles playing music was the thing to do;” the only difference with filk is that they sing about Dr. Demento instead of LSD.

A filker (not Gary Hanak)

Hanak has produced two CDs — one all-original, and the other parodies — and finds great joy in sharing his creations with others. While many in the community are purists (no electronic instruments, must adhere to a book of traditional “filk hymnals”), he has no trouble freeing himself from those confines:

“I’ve got a tune about whales being transported to an ocean world (based on an Alan Dean Foster story); another track of mine is a Star Trek-themed song set to the music of Big Yellow Taxi (a Joni Mitchell song); I’ve also got one about cats, of course…”

While Hanak takes great pride in his songs, he has no plans to widely monetize them. For a brief time after grad school, he tried to cut it as a musician for a living, but “enjoyed eating food more;” today, he’s content as a hobbyist. But according to him (and others), there are a rare few in the filk community who have made a full-time living out of it — though they’re “not exactly beating at the Taj Mahal’s doors in regards to profit.”

![]()

Tom Smith is the Bob Dylan of filk music, and — as Gary Hanak puts it — is “phenomenally gifted in this particular genre of being twisted and sick.”

With a mess of unkempt hair, a scraggly beard, and piercing lyrical prowess, he’s secured a Jerry Garcia-esque cult following that extends beyond his genre’s niche community. When told that others have referred to him as a filk guru, he sheepishly downplays his role — “I think they just mean that I resemble Buddha” — but his contributions shouldn’t be understated.

Smith fits the typical profile of a sci-fi connoisseur. At the age of six, he recalls simultaneously reading the New American Bible and D’Aulaires’ Book of Greek Myth — “and that’s how an Atheist is born,” he adds.

But Smith was also raised in an environment which nurtured his artistic inclinations: his mother was a nightclub singer and his father was dancer in 1950s Detroit.

Filking, which was the perfect marriage of his interests, began for Smith in 1985 as “an oblique effort to get laid.” He bought a guitar at a consignment shop, taught himself to play with a few books, and started busking at cons.

The Twelve Days of Star Wars (Tom Smith)

For years, it remained a hobby while Smith retained a day job working for a bank. But in 2004, his company dwindled and he was laid off. He spent the next six months “trying to get back in the rat race;” when his unemployment ran out and he realized he was barely making it by, he had to resort to drastic measures, and decided he’d take a crack at making filk his full-time job.

By this time, Smith had developed a reputation as “The World’s Fastest Filker,” and had devout followings at a number of cons throughout the Midwest. He possesses the ability to rapidly write “really really good” songs in a mere matter of minutes (by the end of a 30-minute phone interview, he’d written and recited a rhyming verse to me, using my name).

Cruisin’ for chicks on Google Maps,

The be-all and end-all of killer apps,

Nine billion panoramic street view snaps,

Cruisin’ for chicks on Google Maps.

— Cruisin’ for Chicks on Google Maps (Tom Smith)

From 2004 through 2011, he was able scrape together a living, bouncing around from con to con, and playing private parties. Though cons didn’t pay him to perform, they’d pay for his travel expenses, put him in a hotel room, give him a “per diem” for daily meals, and allow him to sell his CDs. He set up a Bandcamp (online music store), offered his tracks at a “pay what you want” rate, and saw modest returns.

He also set up a website on which he offers (to this day) a “personalized” filk song about anything you’d like, to the tune of $349. He calls them “Smithtunes:”

“If you’re paying for a song, especially as a gift, you want it to be good. I don’t want to take your money for hack work — my pride, skill, and reputation are on the line. And you want a song that touches your heart, makes you laugh, makes you cry, makes things special — a song you’ll want to listen to and sing again and again.”

For some time, says Smith, the service did well; after making a series of appearances on NPR and Dr. Demento, he saw an increased demand. In one such case, he tells us, a man surprised his wife with a Tom Smith original, only to be gifted one in return.

Businesses also paid Smith to write songs — he wrote a few for webcomics Accidental Centaurs and Girl Genius (both of which are immensely popular in the sci-fi community), and was commissioned to write a series for Steve Jackson Games, a board game company that invented the successful Munchkin series. He even composed the official song for National Talk Like a Pirate Day (September 19, by the way).

Hermoine Granger, the Pirate Queen (Tom Smith)

Following Jim Henson’s passing, Smith wrote “A Boy and His Frog,” a song from Kermit’s perspective bemoaning the loss of The Muppets creator. The Henson Family received the track, and loved it, says Smith:

“The last thing the Henson family wants is some unknown sci-fi guy sending them a song, saying ‘I have written this song in tribute of your lost warrior’ — but when you get praise from the Henson family — it’s stuff like this that has made me happy in life.”

Around 2009-2010, the tanking economy stressed Smith’s filk business. In conjunction, he tore his quadriceps muscle while “attempting to take the stage” at a con, rendering him immobile for a while. His health declined, and he became housebound — but remained in high spirits. “I’ve written a few songs about not being a big star and being okay with it, because I’ve have more fun than I ever could’ve imagined,” he says.

While Smith hasn’t been a “financial success,” he gets to “go to conventions, get hugs from beautiful women, and perform” — and he survives just fine. Moreover, his songs have had a tremendous impact on the filk community and beyond: when he recently met his hero, “science fiction god” Larry Niven, Niven proceeded to burst into song, reciting one of Smith’s more popular numbers word-for-word.

![]()

There are a few others who make a living from filk music, but in the much broader definition of the genre.

Luke Collis Sienkowski, better known by his moniker “the great Luke Ski” coined “filk rap,” and had the most requested songs on the Dr. Demento show for numerous years. His songs — “Peter Parker,” “Stealing Like a Hobbit,” “Snoopy the Dogg,” and the like — riff on everything from Star Wars, to Keanu Reeves, to Hamlet. He plays no instrument, rapping to pre-recorded music at cons and other events. Between con appearances, independent music sales, and his podcast, “Luke and Carrie’s Bad Rapport,” he’s scraped together a living with sci-fi themed parodies.

The Great Luke Ski just doin’ his thing; Source: Tom Rockwell

Others, like S.J. Tucker (“sooj”), are popular performing artists who don’t necessarily confine themselves to filk, but widely integrate its concepts into their music. One of her albums, Haphazard, is described by newWitch magazine as “an album that no Pagan should be without.” A semi-successful music career has allowed her to transition into science fiction writing and other mediums.

Piano Squall, a classically-trained pianist who’s achieved underground fame composing soundtracks for anime, had humble roots at sci-fi cons, playing filk tunes.

Filk has also spawned extensive subcultures, like “wizard rock” — a group of Harry Potter-crazed filkers who exclusively cover “wizard-related fanfare.” With band names like “The Crumple-Horned Snorklacks” and “The Bubbling Humdingers,” the bands have established followings at designated Harry Potter cons, as well as at magic and witchcraft festivals.

A Final Salute

Source: TigreRoux

Filk is by nature, all-inclusive. “We’re all social misfits in one way or another,” a con regular tells us, “ so, the idea of going up in front of everybody is terrifying. We’ve been there and we understand, so we encourage everyone who pitches in.”

For many filkers, the music is a “mighty shield” that protects them on the “battleground” of society. Filk evokes the negative stereotypes of fans circulated by the mass media, but realigns them in a direction more sympathetic to the community’s own interests.

For instance, in response to an insulting Los Angeles Herald review of Star Trek II in 1982, a collaboration of filkers known as the LA Filkharmonics wrote “Science Wonks, Wimps, and Nerds,” a song that flipped negative connotations of sci-fi fans (ie. basement-dwelling geeks with colossal figurine collections), and instead promoted them as “prophets, inventors, and movers.”

Bill Ropers’ filk song “Wind From Rainbow’s End” does something similar, telling the story of a lonely, bullied schoolboy who finds escape through science fiction books. But his song ends with a fair warning: “once you find your way into a fantasy world, it’s hard to escape.”

Undoubtedly, filkers are dreamers — but they are dreamers who are translating fantasies into accomplishments that speak much louder than words. For some, like Tom Smith, filk even reengineered dismal realities:

“Ten years ago, when I had my last job, I stared at my computer all day. I was dying, my health was not good — my soul was being crushed. Losing that job and putting myself into filk was the absolute best thing that’s ever happened to me.”

Smith’s voice noticeably changes over the phone, and for a brief moment, the “World’s Fastest Filker” slows his cadence to a crawl. “I’ve gone to so many places I never imagined I would ever get to,” he says, almost whispering. “I was able to come out with…everything.”

![]()

This post was written by Zachary Crockett. Follow him on Twitter here, or Google Plus here.