![]()

Every November, deep in the White House’s rose gardens, the President of the United States raises his hand above a specially-selected turkey’s head, and gives it a Presidential pardon.

Today, Mr. Obama will honor the 31st such bird, a 40-pounder named “Abe.”

The act supposedly ensures the bird a life free from the shackles of Thanksgiving dinner — a life of aimless roaming, gobbling, and other turkey activities.

But the “tradition” comes with a dark side. Pardoned turkeys are bred from birth to be especially obese for the cameras. They’re sent through a rigorous media boot camp, preparing them for flashbulbs, large crowds, and stressful situations — and all the while, they’re treated like small, feathered kings. Then, as a result of their priming, they die at tender ages, a shadow of what they once were.

The tradition’s unofficial roots extend back to Abraham Lincoln, who, in addition to being our nation’s sixteenth POTUS, was a fanatical animal lover.

Lincoln maintained a healthy stable of White House pets, and he treated them like royalty. His two goats, Nanny and Nanko, routinely joined him in the Presidential carriage. Once, after being scolded by his wife for feeding one of his cats with an ornate utensil, he stood at the dinner table and proudly declared, “If a gold fork was good enough for former President Buchanan, it’s good enough for my Tabby!”

His enthusiasm didn’t wane when it came to turkeys.

In November 1863, in the midst of the Civil War, Lincoln officially proclaimed Thanksgiving Day a national holiday. Shortly thereafter, he selected the annual White House turkey — a brilliant, broad-breasted white bird. Lincoln’s son, Tad, was instantly smitten, and named the creature “Jack.” After the two inevitably became best buds, the boy begged his father to grant the turkey a stay of execution.

When Lincoln got word of his son’s temper tantrum over the Jack’s impending slaughter, he ducked out of a cabinet meeting and issued the bird “an order of reprieve,” sparing Jack’s life.

Over the next year, the turkey became a member of the Lincoln family — and an endless source of entertainment for the President and his cabinet. On Election Day 1864, there were voting booths set up in front of the White House for soldiers to cast their votes; suddenly, the ever-cocky Jack strutted into one of the booths.

“Why is your turkey at the polls? Does he vote?” Lincoln asked his son, after observing the scene from his office.

“No,” replied Tad. “He’s not of age yet.”

***

Starting in 1873, with the Grant administration, it became a customary tradition for the president to be presented a turkey. For nearly 45 years, one man — a Rhode Island poultry farmer named Horace Vose — was responsible for “selecting the noblest gobbler in all that little state” for the White House. In 1947, the National Turkey Federation became the President’s supplier; today, it retains the duty.

For some time, historians surmised that the official pardoning tradition began with Harry S. Truman that same year. In a famous photo, he lingers over his fowl with a smile, seemingly granting it immunity from the dinner table. But archivists at the Harry S. Truman Presidential Library say the photo was nothing more than a publicity stunt for turkey farmers.

“The Trumans,” a historian told The Washington Post, “were not animal people” — and it’s likely that his look of adoration here is nothing more than him fantasizing about slathering the bird in cranberry sauce and stuffing his face.

When the ever-gracious John F. Kennedy was presented with a rafter of turkeys in 1963, he pointed to the largest one — a 55-pound whopper — said “we’ll just let this one go,” and send it off to a petting farm in Washington. But, like Lincoln’s sparing 100 years earlier, it was a one-off: subsequent Presidents didn’t seem to maintain any compassion for the meaty fowl.

So, when did this “timeless American tradition” officially start? Not long ago, it turns out.

Standing before the monstrous bird presented to him on November 14, 1989, President George H.W. Bush became the unintentional father of the turkey pardon. “He looks understandably nervous,” joked Bush, “but let me assure you (and this fine tom turkey) that he will not end up on anyone’s dinner table — not this guy. He’s granted a presidential pardon as of right now.” The bird was sent off to a Virginia farm, presumably to live the rest of his life away from the spotlight.

After Bush’s joke, subsequent Presidents carried on the custom — most expressing total disinterest in the act. “They bring me a big turkey and we let one go so we can eat all the others,” Bill Clinton told the press in 1999.

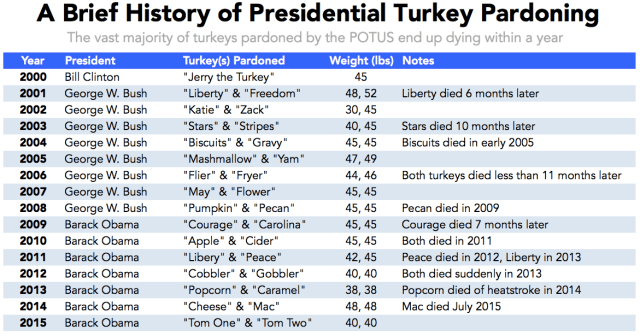

And they certainly brought a big one:

Presidents George W. Bush and Barack Obama started a new trend: pardoning not one, but two turkeys — though often begrudgingly. “Courage will also be spared this terrible and delicious fate,” Obama said in 2009, “[But its only] thanks to the intervention of Malia and Sasha – because I was ready to eat this sucker.”

The Life of a Pardoned Turkey

The turkeys selected for Presidential pardons aren’t just your run of the mill birds — they’re bred from birth to fit the role.

The National Turkey Federation typically selects around 80 newly-hatched turkeys to be considered for the ceremony. They’re then fed a “grain-heavy diet of fortified corn and soybeans” to bulk them up, with the end-goal in the 50-pound range (more than the weight of most dog breeds).

Zachary Crockett, Priceonomics; data via various news archives. Note: this year’s birds, “Tom One” and “Tom Two” were also nicknamed “Honest” and “Abe”

From there, the flock is narrowed down to the “20 largest and best-behaved,” and they embark on their next phase of training: preparing for fame.

A pardoned turkey must be well-attuned to the rigors of the spotlight, and must handle its 15 minutes with grace and regality, so they are put through an extensive course of scenarios — flash photography, large crowds, and loud noises — to gauge their behavior. Usually, it comes down to two birds, ultimately hand-picked by the White House staff.

Leading up to the ceremony, the two turkeys are royalty. Last year’s cluckers, two birds from Ohio named Mac and Cheese, were treated to their own room at Washington’s Willard InterContinental Hotel to the tune of $350 a night. The floor was caked in wood shavings, grains, and feathers as the goliath fowl gobbled their way between the queen sized beds and in-room bar.

But life after the pardon — when everyone’s forgotten them — is historically grim.

Lights, camera, turkey: 2013’s pardoned turkeys prepare for their close-ups (National Turkey Federation)

For years, they were sent to aptly-named Frying Pan Park in Virginia; starting in 2005, they were shipped off to Disneyland Resort in California, where they became a spectacle for incredulous tourists. When ABC News visited one such farm in search of past pardoned turkeys, they learned the disappointing truth: “we usually just find ‘em and they’re dead,” a breeder told the crew. “Their flesh has grown so fast, and their heart and their bones and their other organs can’t catch up.”

It’s a sad truth. Because pardoned turkeys are bred to be robust showmen, they often live incredibly short lives. They are stuffed with a mineral-enhanced diet of corn and soybeans, and their complications are not unlike those of obese humans: heart disease, joint damage, respiratory failure, organ failure.

“The bird is bred for the table,” says one turkey breeder, “not for longevity.” As a result, they rarely reach the five-year average age of their wild counterparts. Of the past eight turkeys selected for pardoning, seven met their end less than a year after the ceremony. With the exception of “Cheese,” one of last year’s birds, every turkey ever honored by the President is dead today.

Though celebrated as a kind-hearted gesture, the Presidential turkey pardon seems to be something of a Hunger Games-esque nightmare for the fowls involved, where even the “winners” aren’t really winners at all.

![]()

This post was written by Zachary Crockett. You can follow him on Twitter at @zzcrockett

Our next post charts the rise of Bayesian statistics. To get notified when we post it → join our email list.