The Beatles made a big impact on pop music, but the one made by 1990s rap was even bigger

Humans have been making and listening to music for a really long time. But every once in a while, the kind of music people like to listen to changes. And sometimes it changes a lot.

In 1850s, Franz Lizst’s technically demanding Romantic compositions for solo piano had the ladies swooning. A century later, Elvis Presley did the same belting simple lyrics over three chords on a guitar. A few short decades after that, Coolio topped the charts with bassy synth, snare, and vocals that mostly consisted of a rhythmically-spoken monologue.

There’s no doubt that music changes over time, especially popular music. But it’s rarely easy to say, definitively, exactly how it changed and when.

Now, a group of scientists publishing in the Royal Society of Science says they’ve figured out how to use data sniff-out the most pivotal periods in the history of popular music. They hope that their approach will bring some objectivity to debates about trends in musical history.

“You can say, ‘This is really when it happened,’” one of the authors, Armand Leroi, told the LA Times. “It’s not just, ‘Things were really cool at CBGB’s or on the Sunset Strip back then.’”

It turns out that ‘it’ — the biggest musical revolution in the history of popular music — really happened in 1991, with the rise of rap and hip hop to the pop charts.

Making a Data Set Out of the Hot 100

The researchers started with the Billboard Hot 100, a list of the most-successful singles in America dating back to 1958. The Hot 100 is published weekly, but songs will often remain on the chart week to week. They took the charts from between 1960 and 2010 and used Last.fm to get 30-second-long audio segments of as many as they could — 17,094 songs, or 86% of the unique singles on the Hot 100 from 1960-2010.

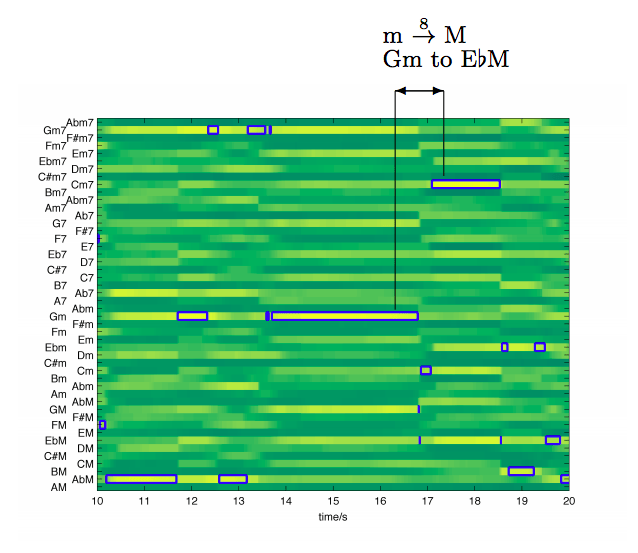

Then they fed these 30-second segments into a couple of programs to analyze them quantitatively. They used NNLS Chroma to extract the most salient chords from the audio. Then they broke their song segments into relative chord changes. A change from C Major to A minor would be represented as M.9.m — i.e. a change from a Major chord to a minor chord, with the second chord’s root nine half-steps higher than the first chord’s.

The highlighted bars show the loudest chords

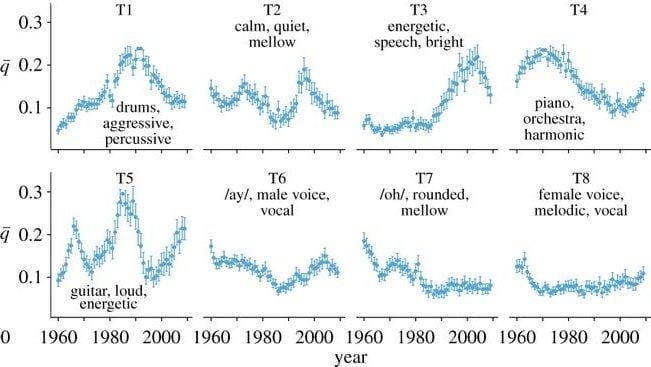

Then they did something similar for timbre, using mel-frequency cepstral coefficients (MFCCs), “which approximate the human auditory system’s response” to sound. This gave them a quantitative way to represent timbre. With this, they were able to algorithmically group very short snippets of these songs into audio files like the ones below, based on timbre type. You can listen to these files — which sound pretty crazy — here.

They then had volunteers annotate these clusters by hand, selecting from the following tag set, (including tags like mellow, aggressive, dark, bright, calm, energetic, smooth, percussive, instrument: piano, `ah’, `ee’, `ooh’).

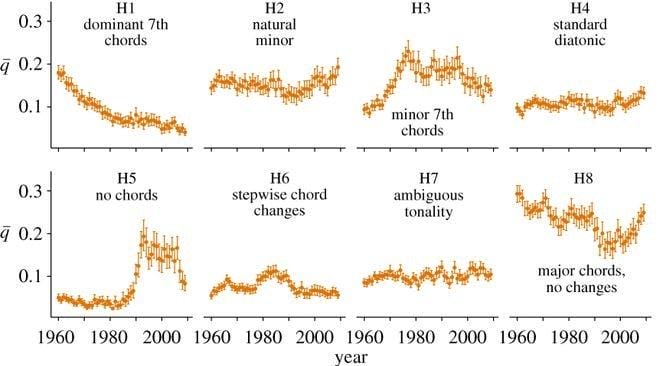

Then they made topic sets of chord changes or timbre tags that frequently occurred together, and not with other chords changes or timbre tags. In doing so they borrowed a tool out of textual analysis. Then they tracked the frequency with which these topics occurred across the Hot 100 over the decades:

Harmonic topics over the decades: H3 correlates most highly to songs tagged disco, funk, and RnB, hence this topic’s swell in popularity in the 1970s. H5 — no chords — correlates most highly to songs tagged rap and hip hop, thus the sudden rise in chordless songs in the 1990s.

Timbral topics over the decades: T4 seems to show the sinusoidal popularity of harmonic piano pop; T5, the repeated rise and fall of energetic guitar rock

About Those Revolutions

In 1990, in the upswing of the biggest musical revolution of the past 50 years, Biz Markie’s Just a Friend peaked at number 9 on the Hot 100

This analysis, while by no means capturing every feature of these songs, still seems to be tracking some musically meaningful aspects of them. This study is able to point out that, timbrally, Fall-out Boy is the most “guitar, loud, energetic” artist in the Hot 100 in the past 50 years. And it’s also able to tell that minor 7th chord changes were basically introduced with disco in the 1970s and haven’t left pop music since.

To study how music changed over time, they plotted the rate of change in the proportions of harmonic and timbral topics. “[The analysis] suggested that while musical evolution was ceaseless,” the authors write, “there were periods of relative stasis punctuated by periods of rapid change.”

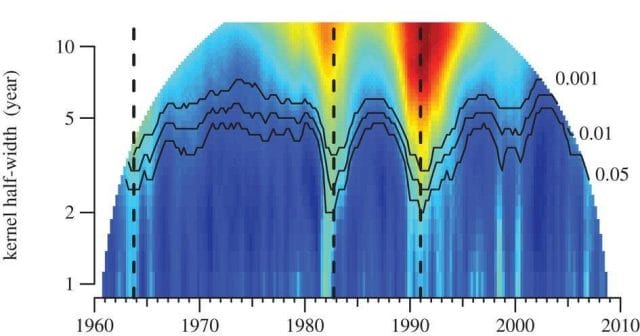

Rate of change, represented on a color gradient, for windows of time ranging from 1 to 10 years following each quarter from January 1960 through December 2010. Blue coordinates indicate least change, followed by green, then yellow, with red and brown being the most. Significant revolutions are marked with vertical black lines.

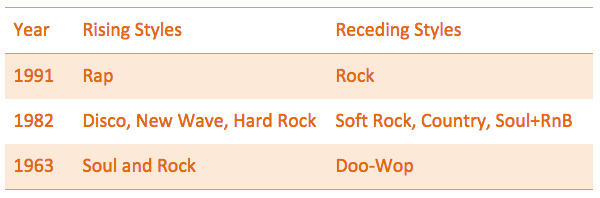

The climactic periods in the history of American popular music are: the last quarter of 1963, the last quarter of 1982, and the first quarter of 1991.

As they write in the paper, the biggest revolution was the one in 1991 correlated to the proliferation of rap music to the popular charts. “The rise of rap and related genres,” the paper reads, “appears to be the single most important event that has shaped the musical structure of the American charts in the period that we studied.”

Major Musical Revolutions 1960-2010

Their analysis didn’t end there: the researchers also used their data to critique the “British Invasion” theory of American rock and roll. From the paper:

On 26 December 1963, The Beatles released I want to hold your hand in the USA. They were swiftly followed by dozens of British acts who, over the next few years, flooded the American charts. It is often claimed that this ’British Invasion’ was responsible for musical changes of the time.

But the revolution of the 1960s hit its peak in late 1963. Their analysis revealed that the “evolutionary trajectories” of many musical styles were already established by the time the Beatles hit the scene, “implying that, whereas the British may have contributed to this revolution, they could not have been entirely responsible for it.” Groups like the Beatles and the Rolling Stones did, “fanned [the revolution’s] flames.”

Earlier Revolutions

Leroi said he was surprised that the rap revolution of the 1990s made a bigger splash in the data than the Beatles and their generation did. “Being a victim of boomer ideology, I would have guessed it was [the 1960s],” he told the LA Times.

The rap revolution of 1991 might be challenged by future research, the paper hints. “We are interested,” the authors write in the conclusion, “in extending the temporal sample to at least the 1940s — if only to see whether 1955 was, as many have claimed, the birth date of Rock’n’Roll.”

This post was written by Rosie Cima; you can follow her on Twitter here. To get occasional notifications when we write blog posts, please sign up for our email list