Political debates may take place over espressos in coffee shops and in stately assembly halls, but people’s politics may be more influenced by primal forces than they realize.

This at least is the implication of a paper published in the May 2013 issue of Psychological Science entitled “The Ancestral Logic of Politics,” which reports on the link between men’s upper body strength and certain political views.

The authors start with a model from behavioral ecology that seeks to explain how animals divide resources amongst themselves. Called the “asymmetric war of attrition,” the model argues that “greater fighting ability leads animals to bargain for a disproportionate share of contested resources.” Animals will only keep the resources that they can defend, so strong animals will take a greater share of food or other useful things while their weaker peers more readily cede resources that a stronger male could take by force.

Although humans have a history of cooperation, the authors point to ecologists’ documenting of early human societies acting according to this principle. This suggests that evolutionary pressures would select people to assess their peers strength and use it to make decisions about taking or giving up resources. Given that the distance between us and our early ancestors is a relative blink in evolution’s eye, they hypothesize that the same model could be at work today.

The professors look at a sample of individuals from the US, Argentina and Denmark and their socioeconomic level, physical strength (using bicep size as a proxy), and support for political policies that redistribute resources from the rich to the poor (as measured through questionnaires). They hypothesize that under their “evolutionarily-based theory of political orientation,” strong men will favor redistribution if they are poor and oppose it if they are rich. Just like in the primal past, they should expect to receive resources, but not to give up their own.

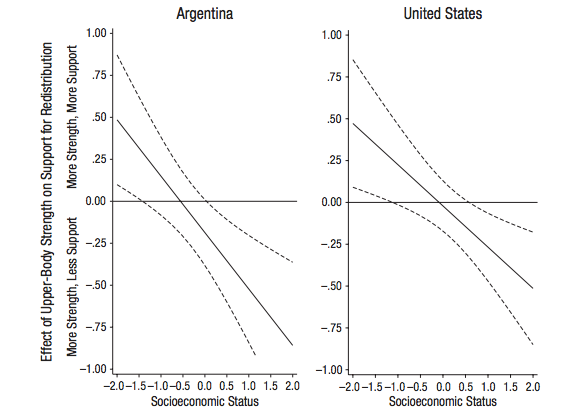

Their results support the hypothesis. A man’s strength correlated with his support for or opposition to redistributional policies depending on whether he was rich or poor. This is shown below for the US and Argentina. The solid line is the effect in strong men and the dotted lines represent confidence intervals of 90%.

In contrast, socioeconomically poor men with small biceps showed less support for redistribution (which would be in their self-interest) than their strong counterparts. Richer men with small biceps demonstrated less opposition to redistribution than their rich and strong counterparts. The effect was not seen in woman, in line with the authors’ thinking that only men would have regularly contested for resources in early human history.

Michael Petersen, one of the studies authors, sums up the surprising finding:

“Our results demonstrate that physically weak males are more reluctant than physically strong males to assert their self-interest — just as if disputes over national policies were a matter of direct physical confrontation among small numbers of individuals, rather than abstract electoral dynamics among millions.”

Given that support for redistribution of wealth is often divided along party lines, one implication of this work would seem to be that strength can influence whether someone is conservative or liberal. However, the authors found the effect to be independent of political orientation.

They take this to mean that political ideology is “regulated by distinct evolutionarily relevant variables.” A skeptic may counter that when people think comprehensively about political views, rather than about one policy in isolation, they do so more cerebrally. If that is the case, it would limit the impact of evolutionary models like the one discussed by the authors.

Regardless, this study still suggests that even in a world of people performing analytical tasks in front of computers all day, our most intellectual views can be influenced by the same forces that incite monkeys to fling their feces at each other.

This post was written by Alex Mayyasi. Follow him on Twitter here or Google Plus. To get occasional notifications when we write blog posts, sign up for our email list.