“The time of the horse’s greatest usefulness is past, and the only solution of the horse problem will be found in introducing the meat as an edible.”

— The New York Times, 1895

![]()

In mid-2013, millions of European beef eaters received unpalatable news: for years, they’d been unknowingly eating horse meat.

After extensively testing meat throughout the continent, Ireland’s Food Safety Authority chronicled dozens of products “tainted” with horse DNA. Tasco hamburgers, widely consumed in Europe, were found to be 29% esquine; worse, the “beef” in French manufacturer Comigel’s lasagne proved to be composed of 60% to 100% horse meat. The effects of this scandal — appropriately dubbed “Horsegate” — even trickled down to major chains, which were forced to recall truckloads of meat: Nestle, Burger King, and IKEA (whose savory “Swedish beef meatballs” were anything but) all lost millions of dollars worth of goods.

From afar, Americans collectively dry heaved. The mere thought of consuming horses seems disgusting: they are our friends, our companions, our idolized Derby winners. John Wayne rides his trusty stallion into the sunset, and breeders treat their prized equine like royalty. Surely, we thought, these creatures are not for eating.

History tells a different tale.

For more than 150 years, Americans have eaten horse meat — both out of necessity, and for its unique taste. And at times, didn’t just eat it: they loved it, savored it, and treasured every last morsel. Our strange relationship with horses goes beyond companionship and into the realms of culinary enjoyment.

We Ate Horses

For no less than 30,000 years, humans have hunted, slaughtered, and dined on the rich, stringy meat of horses. Some of the oldest cave paintings ever discovered, in modern-day France’s Chauvet Cave, depict the ritual hunting of horses for sustenance; archeological excavations in the same area have uncovered hundreds of thousands of equine remains in burial pits. Historians estimate that by around 4500 BC, the animals had been domesticated and valued not only for their flesh, but as companions and a method of transportation. This didn’t stop people from continuing to eat them.

The modern Western world’s taste for horse meat began in 18th century France, while the country was entrenched in its revolution. Initially, the meat was consumed out of desperation — commoners and soldiers were encouraged to sustain themselves by killing and eating the aristocracy’s foals — but by the mid-1800s, the French had grown fond of horse, serving it in soups, roasted, boiled, and in a special dish, “bœuf à la mode.”

In 1866, the French government officially legalized both the consumption and production of horse meat, and dozens of specialty butcher shops were opened in Paris to supply a growing demand. An 1870 article in French publication The Food Journal declared, without qualms, the arrival of the new meat in Europe:

“The almost impossibility of obtaining beef and mutton naturally forced the use of horse-meat upon the people, and, after a little hesitation, it has been most cheerfully accepted. Some persons prefer it to beef, from the gamey flavour which it possesses…As good wholesome food it has been universally eaten, and the soup made from it is declared by everyone to be superior to that from beef.”

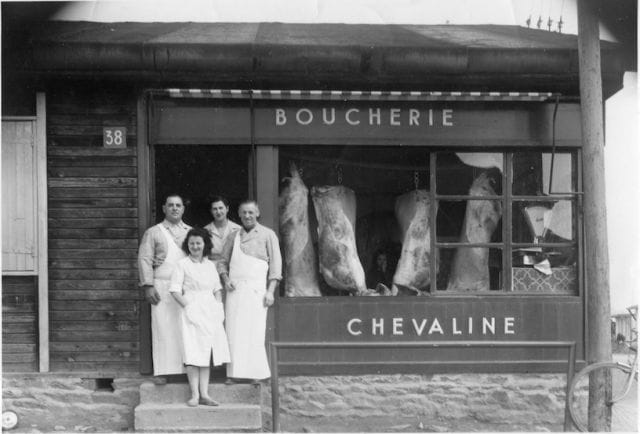

Horse butchery in France (c. early 20th century)

Over the following 13 years, France’s horse meat consumption ballooned from 171,300 pounds per year to 1,982,620 pounds per year — and by 1880, horse flesh was selling for a higher price than beef. It was not only consumed, but regarded as delicacy — “tender and rather sweet in flavor,” according to one 19th century diner. At Lyons, a giant “horse-eating banquet” was held each year, beginning in the mid-1860s, enticing guests with the following advertisement:

“The fashion of eating horseflesh is stealing upon us rapidly and surely; the use of horse-flesh is an immense benefit to public health and to commerce. It is as good as beef, healthier than pork, and three times cheaper than any other meat. But is horse meat agreeable to the taste? YES!”

An American abroad in Paris in 1864, who attended the banquet, fondly recalled his experience in a letter to the New York Times:

“At this banquet, at which was served up a young horse of five years old, it was decided that horse soup was better than beef soup, that corned beef was better than corned horse, but that roast horse was better than roast beef. Hereafter, we may expect to see all the horses killed in European battles eaten by their riders.”

***

Meanwhile eating horses also began to gain acceptance in the United States — but at first, only in the face of major quandaries encountered by Westward-bound pioneers. When famed explorer John C. Frémont ran into difficulty difficulty leading his fifth expedition to California in 1854, he resorted to eating his steed:

“The food for a portion of the way was horse meat. Whenever a horse gave out, if the game was not plenty, he was slaughtered, and his stringy and lean muscles were divided with the strictest economy.”

As Americans endured through the Panic of 1857 and a pre-Civil War recession, butchers on the East coast began to cut corners by secretly selling horse meat marketed as beef, and offering it at substantially lower prices to entice the meat-deprived public. Newspapers reported that Bostonians were indulging in “liberal quantities of sausages for lunch daily” — until they found out they’d been eating horse.

“Men are in the habit of working up dead horse into sausage meat and prime bolognas,” wrote the Philadelphia Evening Bulletin in 1858, “and then they sell it as cow.” At once, the thousands of city dwellers who’d once thoroughly enjoyed the meat now could hardly bear the thought of what they’d wolfed down.

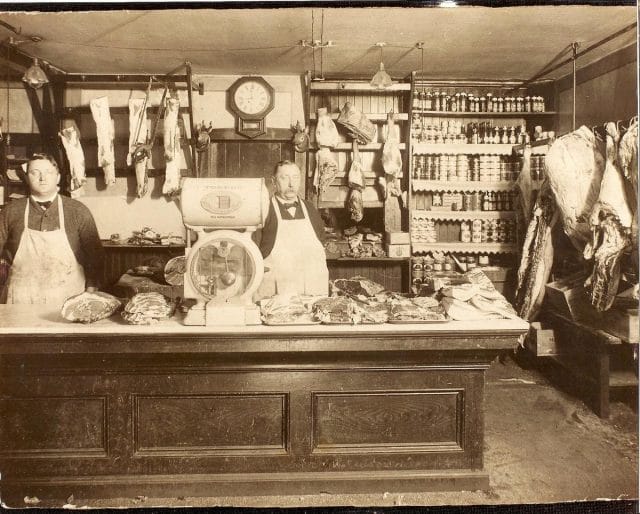

Dozens of East coast butcheries engaged in the deceptive sale of horse meat in the mid-19th century

While most Americans strongly opposed the consumption of horse meat, others continued to knowingly eat it — though, as before, out of necessity. In an 1863 Civil War account, General William Rosecrans wrote of his group’s need to sustain itself in times of hardship. Without remorse — and almost affectionately — he recounts dining on his horse:

“Every particularly fine horse was shot, and, after bleeding the animal, we would proceed to cut steaks from him, which we cooked and ate with much relish. There is little difference between beef and horse meat, if properly cooked.”

These sorts of accounts, which endorsed the meat as perfectly edible, did little to persuade the general public. Over the final decade of the 1800s, dozens of horse meat operations popped up across the country. While most were scams (horse meat disguised as beef), other, more legitimate sellers were able to continue their businesses, as the U.S. had no laws in place banning the production or consumption of the meat.

After realizing the huge horse meat market emerging in France, one entrepreneur, a New York butcher by the name of Henry Bosse, opened a horse slaughterhouse and began exporting the meat. Typically, county contractors would offer horse owners wishing to get rid of their old stock $1.50 per horse; Bosse offered these owners $4 to $10 per head, and soon amassed a gargantuan stable of horses. By 1891, he was exporting 56,000 pounds of horse meat every two weeks at an extreme profit:

“The hair, hide, bones, and organs of the old horses, when resold by Bosse to the fertilizer manufacturers, pay the expense of the whole business, and the sale of the alleged horse beef in Europe, which brings about 7 cents per pound, is, after deducting the estimated cost of freightage at about one-third of a cent per pound, clear profit. Bosse’s profits are said to have reached over $1,000 per week [$26,000 in 2015 dollars].”

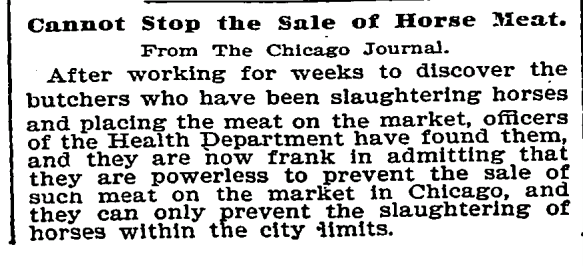

Though New York’s Department of Health ferociously fought to quell Bosse’s venture, he was eventually permitted to continue, and others began to follow suit. From the backwoods of New Jersey to small-town Connecticut, horse meat export businesses flourished, and they couldn’t be stopped.

Chicago Journal headline, October 7, 1894

The practice was replicated in the newly-settled West, where horses had dwindled in value from $50 per head to $2 to $3 per head. “The time of the horse’s greatest usefulness is past,” declared the New York Times, “and the only solution of the horse problem will be found in introducing the meat as an edible.”

At the same time, demand continued to soar abroad — not just in France, but in Germany and Austria, where beef and pork, at 25 cents per pound, had become too expensive for the 90% of the population earning less than 75 cents a day. Financially-ailing farmers began to increasingly argue for the right to slaughter, eat, and export horse meat as a way to sustain themselves. One journalist voiced this opinion in an 1895 op-ed:

“Horses can be raised in the US much cheaper than cattle. they can be slaughtered at any of the American packing houses as easily as cattle, and they can be shipped alive across the sea much more easily than cattle. With the astonishingly rapid disuse of horses in America, their raising is far from being the profitable industry it once was.

If the ranchman, however, can make the raising of horses for food profitable, why should he not do it?”

And that’s exactly what happened.

On July 19, 1895, the first-ever industrial horse meat packing plant opened in Portland, Oregon. Armed with $10,000 worth of machinery for “slaughtering, packaging, and shipping meat,” the plant set about shipping thousands of tonnes of meat every week. “The selling and eating of horse meat is very repulsive to the average American,” admitted its owner, “but it is not so clear that it is forbidden by the law.”

Horse Meat Gets Trendy

Suddenly, at the turn of the century, horse meat gained an underground cult following in the United States. Once only eaten in times of economic struggle, its taboo nature now gave it an aura of mystery; wealthy, educated “sirs” indulged in it with reckless abandon.

At Kansas City’s Veterinary College’s swanky graduation ceremony in 1898, “not a morsel of meat other than the flesh of horse” was served. “From soup to roast, it was all horse,” reported the Times. “The students and faculty of the college…made merry, and insisted that the repast was appetizing.”

Not to be left out, Chicagoans began to indulge in horse meat to the tune of 200,000 pounds per month — or about 500 horses. “A great many shops in the city are selling large quantities of horse meat every week,” then-Food Commissioner R.W. Patterson noted, “and the people who are buying it keep coming back for more, showing that they like it.”

National Headline, June 1902

In 1905, Harvard University’s Faculty Club integrated “horse steaks” into their menu. “Its very oddity — even repulsiveness to the outside world — reinforced their sense of being members of a unique and special tribe,” wrote the Times. (Indeed, the dish was so revered by the staff, that it continued to be served well into the 1970s, despite social stigmas.)

The mindset toward horse consumption began to shift — partly in thanks to a changing culinary landscape. Between 1900 and 1910, the number of food and dairy cattle in the US decreased by nearly 10%; in the same time period, the US population increased by 27%, creating a shortage of meat. Whereas animal rights groups once opposed horse slaughter, they now began to endorse it as more humane than forcing aging, crippled animals to work.

With the introduction of the 1908 Model-T and the widespread use of the automobile, horses also began to lose their luster a bit as man’s faithful companions; this eased apprehension about putting them on the table with a side of potatoes (“It is becoming much too expensive a luxury to feed a horse,” argued one critic).

At the same time, the war in Europe was draining the U.S. of food supplies at an alarming rate. By 1915, New York City’s Board of Health, which had once rejected horse meat as “unsanitary,” now touted it is a sustainable wartime alternative for meatless U.S. citizens. “No longer will the worn out horse find his way to the bone-yard,” proclaimed the board’s Commissioner. “Instead, he will be fattened up in order to give the thrifty another source of food supply.”

Prominent voices began to sprout up championing the merits of the meat. Dean Hoskins, an influential veterinarian at N.Y.U., toured the Eastern states, lecturing in its defense. “It is palatable, tender, and sweet,” he told a crowd at one conference. “There is no reason that horses physically unfit for work, but otherwise healthy, shouldn’t be used as food.”

“There is no scientific reason why horse meat, now sold in some cities, should not be eaten,” another commenter opined. “It is sweeter than beef, but coarser, heavier, stringier and darker.”

The economics of the meat backed up these assertions: at 15 cents per pound, it was 3 times less expensive than beef and pork.

***

During the Great Depression and World War II, horse meat continued to gain acceptance in popular culture — especially as other meats were strictly rationed, and supplies were cut short. Within a few years, horse meat became a $100 million industry.

Butcher shops and processing plants were established across the states, from Los Angeles to Connecticut, and flourished. In Massachusetts, one Boston wholesaler reported selling out of 30,000 pounds of horse meat in less than 48 hours. In Oregon, the meat became “an important item on Portland tables,” with “three times as many horse butchers, selling three times as much meat.” TIME magazine offered advice to housewives on how to best prepare “horse filets.”

No horses were safe from the butcher block, even racehorses. As desperation set in, it was reported that two former prized stallions — one a winner of the French Derby, and the other a Grand Prix champion — had been killed and sold for 10 cents per pound. In their prime, the horses had been valued at over $40,000 each.

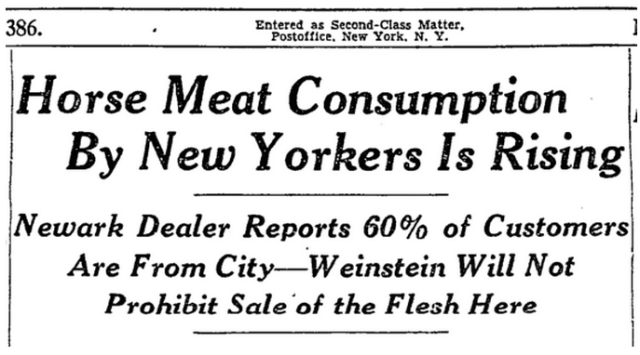

New York Times headline, September 26, 1946

Meanwhile, in New Jersey and New York, where authorities had cracked down on horse meat distribution, choice cuts of horse meat went for 17 cents a pound — a fraction of its beef counterpart — and sales increased 75% as a result.

New York’s Health Commissioner, Isreal Weinstein, told the Times that, although many of the dealers were unlicensed, he’d stay out of their way. “Horse meat is just as nutritious and just as good as any other type of meat,” he defended. Just years earlier, New York’s Mayor, Fiorello La Guardia, had decried horse meat as “the most degrading thing [he had] ever seen,” citing moral concerns.

The times were a-changin’ — or so it seemed.

The Horse Meat Crackdown

As the post-war recession wore off and other types of meat become affordable again, the demand for horse meat essentially disappeared. The same horse meat producers who’d been raking in profit during hard times now found themselves destitute and struggling to adjust back to their standard meat products.

Throughout the 1950s and 1960s, many of these butchers dealt with this issue by trying to illegally pass their large supplies of horse meat as beef — and they were substantially punished.

New York Times headline, July 1951

Archive searches yield dozens of arrests for such scams in New York alone, with fines ranging from $100 to $5,000, and jail sentences of up to six years. One major horse meat bust in New Jersey revealed an unlikely force behind the operation: the mafia.

In 1952, the Departments of Health and Markets joined forces to temporarily ban horse meat from a number of U.S. states.

***

If history has proven anything at this point, it is that the popularity and consumption of horse meat fluctuates in accordance with times of hardship in the United States. And of course, it wasn’t long before the next economics dip gave the meat a little comeback.

During the 1973-75 Recession, beef prices skyrocketed, and residents — chiefly those of Connecticut, New Jersey, and New York, turned back to their old friend, horse meat. By this time, horse meat had been legalized for consumption — but only if no other type of meat was sold in conjunction with it.

In April 1973, an entrepreneur named Ken Carlson opened up Connecticut’s first retail horse meat market, offering the meat partly as a novelty item, and partly as a seriously cheap alternative to the then-pricier meats.

Less than two hours into his first day, he’d sold more than 2,000 of his 6,000 pounds of meat, mainly in the form of hamburgers and steaks. At ½ to ¼ the price of beef, the horse meat enticed customers from as far as two states over, who were then subjected to Carlson’s sales pitch: “It’s cut absolutely the same as beef. It’s as tender, and the taste is the same. And there’s practically no waste on it.”

Soon, Carlson’s operation became so popular that he was selling 6,000 pounds a day. He’d subsequently produce a 28-page guide book, “Carlson’s Horse meat Cook Book,” which included recipes for a variety of horse dishes.

But by 1975, the fad had faded once again, and horse meat went back to the chopping block.

Horse Meat Today

Today’s horse meat economy — and the legislation surrounding it — differs greatly from that which we’ve explored.

For one, France is slightly less obsessed with the meat, as is the rest of Europe. Still, about 18% of French households regularly dine on it (as opposed to around 80% at the end of the 19th century). Of these households, consumption is modest — about 5.5 pounds of horse per year. In the last 20 years alone, this number has declined 58%. Ironically, while horse was once favored for its astronomically low prices in France, it is now the country’s second most expensive meat at $20 per kilogram, trailing only veal.

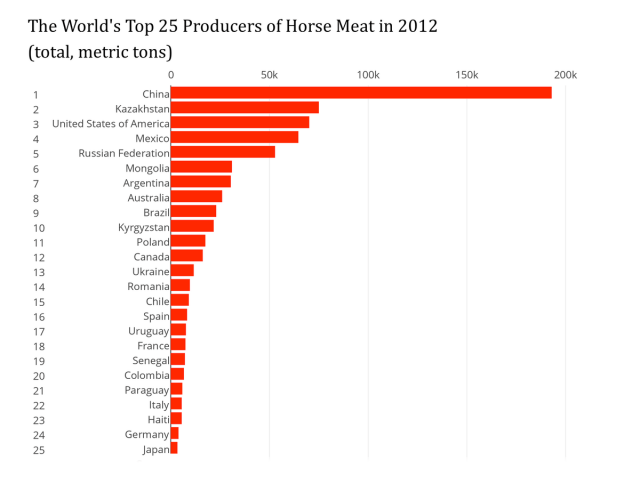

The global market for horse meat production has also dramatically shifted; today, China produces nearly 50% of the world’s supply (keep in mind that much as this meat is also used in zoo animals and domestic pets):

Priceonomics; Data via FAOstat, United Nations

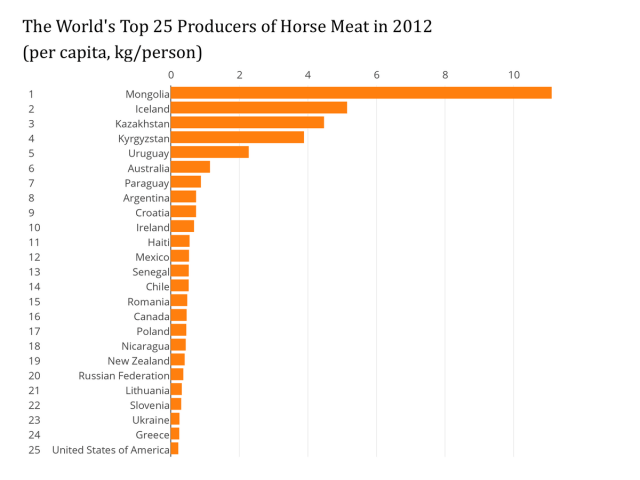

Here’s the same data adjusted for population size (per capita):

Priceonomics; Data via FAOstat, United Nations

Interestingly, the United States has continued to slaughter and export horses for consumption — though various legislation has attempted to combat these operations.

The legality of the practice is usually determined at the state level. For instance, California Proposition 6, enacted in 1998, made it a felony to “possess, transfer, receive, or hold a horse with the intent to kill it, or have it killed, where the person knows, or should have known, that any part of the carcass will be used for human consumption.” In 2007, the Illinois General Assembly likewise moved to outlaw the slaughter of horse for consumption. Since, at least 10 other states have followed suit, including New York and Massachusetts, where the practice once thrived.

All federal attempts to ban horse slaughter for consumption have been unsuccessful — though, in 2007, a provision was enacted that prevented the use of federal funds to conduct mandatory inspections on slaughterhouses; without proper inspections, all but 3 major horse slaughterhouses in the U.S. were permanently shut down. Exporters recouped their losses by simply shipping live horses for slaughter abroad, in Mexico and Canada, where they would be ground up and sent to Europe for consumption. Briefly, from 2011 to 2013, the budget limitation was lifted, but it has since been reenacted.

***

As far as consumption of horse meat within the United States goes, history had verified it as a food reserved for times of economic hardship; today, we steer clear of eating our equine friends. But why?

In the words of one New York Times columnist, “Horses are America’s sacred cows” — they are our companions, our honorable pals. Eating them, it seems, triggers our moral compass. As one NPR commentator elucidates, tongue-in-cheek, “It’s okay to kill a ton of chickens and cows, but kill a horse? By golly, there’s something wrong with you!”

Yet, historically, when we have eaten horse — either out of necessity, or, in the fashion of Harvard professors, for taste — we’ve savored it.

![]()

This post was written by Zachary Crockett. You can follow him on Twitter here.

To get occasional notifications when we write blog posts, please sign up for our email list.